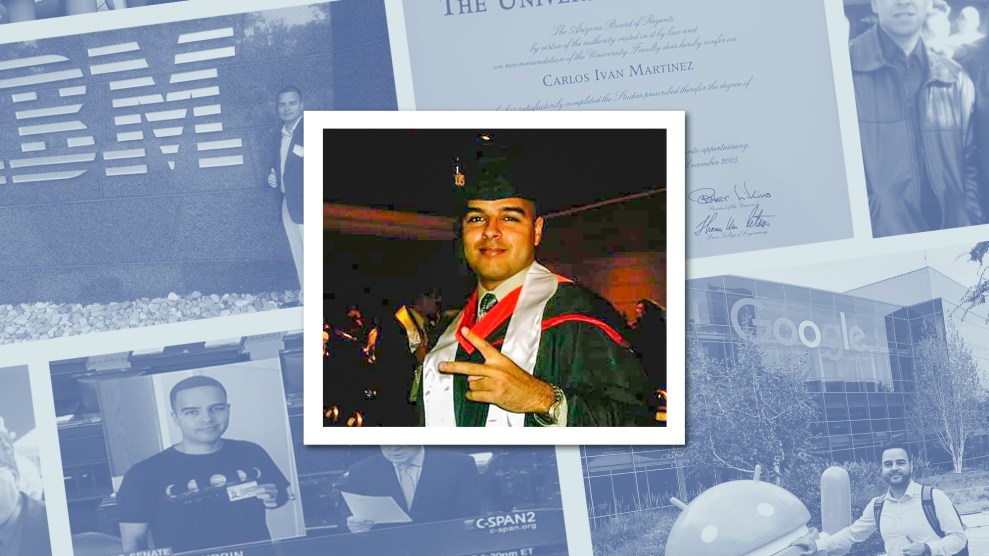

Mother Jones illustration; courtesy of Sylvia Baldenegro

Carlos Martinez was one of the first people in Arizona to get DACA back in 2012. He was literally a poster child for the program: In 2012 and again in 2015, Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) brought a large poster board portrait of Martinez to the Senate floor to help illustrate the need to protect Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals from Republican efforts to kill it.

Durbin argued that Martinez was the kind of Dreamer whose overachieving personality and talents contributed to this country and its economy. He told his fellow senators that though Martinez couldn’t afford a computer when he started college, he ended up graduating with a computer engineering degree and was named top Hispanic graduate of his class at the University of Arizona. He pointed out that Martinez went on to get a master’s and later worked for a major tech company in San Francisco. “Giving up on these Dreamers,” Durbin said, “is giving up on the future of this country.”

But for the last 11 months, Martinez has been locked up in a for-profit immigration detention center in Arizona. He has lost his DACA status and fallen ill with COVID-19. And all of it happened because of a poorly thought-out decision to take a brief detour into Mexico—and an immigration justice system more interested in walls and hardliner rhetoric than in showing the slightest bit of mercy to people who have jumped through hoop after hoop to continue living in the only country they’ve ever called home.

“This has been the toughest time of my life,” Martinez said in a phone call from inside the Eloy Detention Center last week. “Being here is terrible. You never want to be in a place where your freedom is taken away from you, especially when you worked so hard to achieve your goals and be a role model.”

Martinez, 38, has been living in the United States since he was 8 years old. He came with his brother and his parents, Sylvia Baldenegro and Salvador Martinez, from a small city in Sonora, Mexico, 50 miles south of the US border. They settled in Tucson, where Martinez and his brother went to school. Martinez’s mom told me that, from a young age, Martinez was studious and always wanted to succeed in school. Martinez’s father works in construction, and when we spoke on the phone, he had just come home after working in 110-degree heat. “I know what it means to work pico y pala,” he said. “I always told my son to study and work hard, so he wouldn’t have to struggle like I have.”

So when President Obama created DACA by executive action, Martinez was one of the first to apply and receive the two-year work permit that provides protection from deportation. He met all the requirements for DACA back then and continued to meet them every two years when he renewed it. DACA eventually allowed him to get a job at IBM in San Francisco, but after a round of layoffs a few years ago he returned to his parents’ home in Tucson.

Martinez renewed his DACA status in 2018, so it was still valid for another year while he hunted for a job, unsuccessfully, last summer. He told me he flew to California for multiple rounds of interviews for developer gigs at tech companies like Google, Pinterest, and Niantic, the creator of the Pokémon Go app. “I kept getting so close that I was definitely getting frustrated, plus I had the pressures every day thinking DACA might be eliminated,” he said. “Then I heard a couple recruiters say they don’t trust DACA because it may end tomorrow.”

So in an impulsive moment on August 7, 2019, after getting yet another rejection from a potential employer, he decided he’d get out of Tucson for a while to visit his grandmother in Sonora. He was at the US-Mexico border within an hour. But as he drove into Mexico, he realized what he had done: In leaving the United States, he’d just forfeited the protections that went with his DACA status. He turned the car around and was back at the port of entry 45 minutes later, explaining to US Customs and Border agents what had happened. He showed them his DACA permit, hoping that’d be enough to be let in. Instead, he was taken into custody, classified as an “arriving alien,” and sent to the Eloy Detention Center.

“I regret the whole thing. I regret driving over to Mexico, I regret not stopping at the McDonald’s in Nogales, Arizona, not getting an ice cream, and just stopping to think about it,” Martinez said. “Frustration and stress can make you make mistakes or decisions you wouldn’t make under regular circumstances.”

DACA provides temporary protection from deportation and allows recipients to apply for employment. It does not, however, serve as proof of legal status when entering the United States. To leave the country and come back, Martinez needed to have filled out an I-131 form with US Citizenship and Immigration Services requesting advance parole, said Claudia Arévalo, an attorney representing Martinez. That’s how he ended up with a Notice to Appear, the first step in deportation proceedings.

For months, Arévalo tried everything to get Martinez out of Eloy, first requesting bond in a hearing and saying he feared returning to Mexico, and then filing for asylum because that was his only chance to get in front of an immigration judge. “It breaks your heart to see how the system is not taking cases individually,” Arévalo said. “We’re losing a good kid here.”