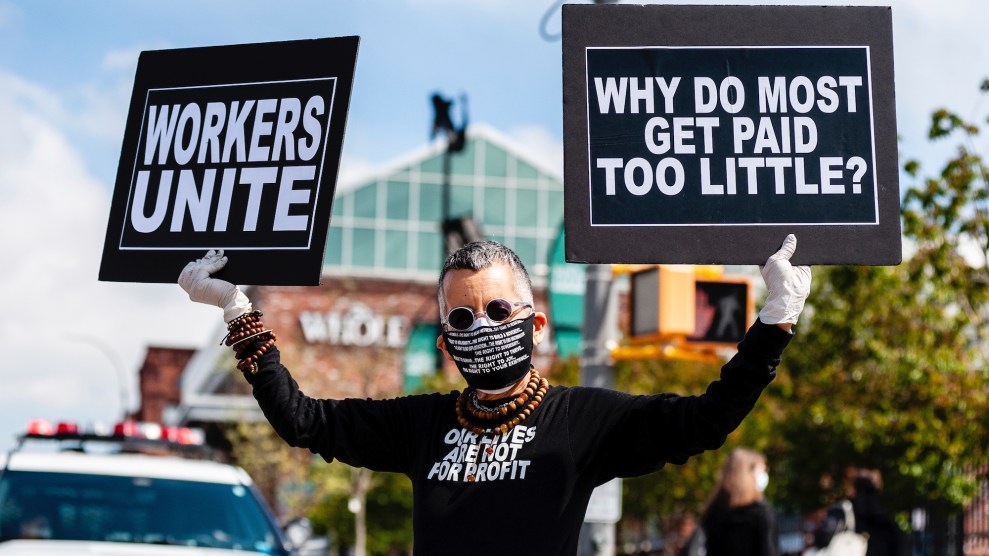

A protestor shows solidarity with essential workers outside a Whole Foods store in Brooklyn, New York, on May 1, 2020.Gabriele Holtermann-Gorden/Sipa/AP

In 2016, Republican candidates did what they often do in Idaho: They swept. Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton by 32 percent. Sen. Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) earned a fourth term with nearly 70 percent support, as did Rep. Raul Labrador (R-Idaho), a leading Tea Partier who dragged his party to the hard right when he entered Congress. In statehouse elections, Republicans took 88 of the 105 statehouse seats up for grabs that year.

These lawmakers were no friends of the Affordable Care Act. Crapo ran ads promising to replace “Obamacare mandates with affordable health care that works.” Labrador told his constituents that “nobody dies because they don’t have access to health care” after he cast his “yea” vote for the House’s ACA repeal bill in May 2017. And Trump, of course, backed a lawsuit aimed at repealing Obamacare through the courts.

But two years later, Idahoans broke with their preferred party—even as they again sent Republicans to Congress and statewide offices. More than 60 percent of them voted to accept a core provision of Obamacare and expand Medicaid coverage to low-income people younger than 65 through a referendum on the 2018 ballot.

That sort of ballot measure—referendums that citizens can place on their statewide ballots to be passed by a popular vote—has become an increasingly popular tactic for pushing progressive policy in GOP strongholds like Idaho. “What we normally see in our political system is hyper-incrementalism at best,” says Jonathan Schleifer, the executive director of the Fairness Project, an organization that leads liberal ballot initiatives on health care and economic equality. ”What ballots allow us to do is to pass really progressive policy in blue states and progressive policy in red states.”

Idahoans had been gearing up for another ballot measure in 2020 to raise the state’s minimum wage from $7.25 to $12 an hour. By the beginning of March, organizers had collected 35,000 of the roughly 55,000 signatures required for a measure to be on the November ballot. But then the pandemic struck, and all signature collection ceased. “We studied the data coming from CDC and concluded that going out in public and interacting with Idahoans to get signatures would put our volunteers at high risk,” Rod Couch, an organizer for Idahoans for a Fair Wage, tells me via email.

Across the country, coronavirus and the efforts to contain it have made it impossible to meet the requirements for putting measures on the ballot. The pandemic will stymie a cycle’s worth of progressive policy that, in some instances, would have directly addressed the medical and financial hardships it has worsened.

To be clear, referendums aren’t just used for progressive causes: Voters in several blue states have decreased their tax payments through ballot measures over the last 40 years. But for liberal causes, ballot measures have forced federal lawmakers to act on policy before their party would demand it. Gay marriage, for example, advanced through a combination of ballot measures that legalized it in some states and refused to ban it in others. Activists fighting for a $15 minimum wage—which has languished at the federal level but made progress through ballot initiatives in several states—hope to repeat that movement’s success with a push like the one they’d planned for Idaho this fall. “The birth of the ballot process was to hold power accountable and given power to the people,” says Chris Melody Fields Figueredo, executive director of the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center. “That’s why direct democracy is such a critical part of a thriving democracy.”

Twenty-seven US states and territories allow for ballot measures, and in order for a proposed measure to make it onto the ballot, organizers need to collect some minimum number of handwritten signatures. “Normally it is a very grassroots enterprise of walking up to someone on the street, or going into the grocery store and asking people to sign a petition,” explains Schleifer. “Obviously, that’s not safe during a pandemic.”

Indeed, the months of shelter-in-place orders and limited reopening of businesses and public spaces killed off a number of efforts underway for the 2020 elections. In addition to Idaho’s minimum wage campaign, activists in Arizona suspended their signature-gathering for a measure that would have stopped surprise medical billing and increased health care worker pay. In Oregon, a petition for safe gun storage has stopped, as well, as has a push to legalize marijuana in Missouri. Most of these efforts can reboot for the 2022 cycle, but some cannot: A Oklahoma campaign to establish an independent redistricting committee –an effort to combat gerrymandering—will have lost its window of opportunity by then.

In some states, organizers have tried to press forward, asking leniency in either the number of required signatures or the in-person collection demands. Such requests in Massachusetts and Montana have been met with success, but others have run into the buzzsaws that often smash liberal dreams: Conservative judges. By July 1, organizers for Raise the Wage Ohio needed to collect nearly 443,000 signatures in order for their measure to gradually raise Ohio’s minimum wage to $13 an hour to appear on the November ballot. When the pandemic made that task all but impossible, the campaign filed an injunction in county court to reduce the signature threshold or allow for electronic signature gathering, adjustments they argued reflected the containment efforts required for combatting coronavirus. The court rejected their request, citing the risk of fraud. (The campaign appealed the ruling, but decided not to move forward on soliciting more signatures because of the legal stalemate.)

If the measure succeeds, 1.4 million Ohioans would receive a raise, the importance of which is heightened in the midst of the pandemic-induced recession. A number of those low-wage workers are putting their lives at risk in essential jobs, and their peers who have lost their jobs are now receiving paltry unemployment sums because of Ohio’s low minimum wage.

If a similar measure had made its way onto the ballot in Idaho, it would have raised the income of minimum wage-earning Idahoans to a level above the federal poverty line. But the state’s deadline for collecting signatures was May 1, and organizers, unable to resume collection, did not turn any in. Though they’d planned to just regroup for the next cycle, a federal judge ruled on Tuesday that Idaho must accept electronic signatures and extend the deadline by seven weeks to accommodate another ballot initiative that would raise $170 million in education funding through higher taxes. It’s not yet clear if that ruling applies to the minimum wage campaign, but even so, the campaign won’t resume.*

*This piece has been updated to reflect the decision of Idahoans for a Fair Wage to not resume their campaign during the 2020 cycle.