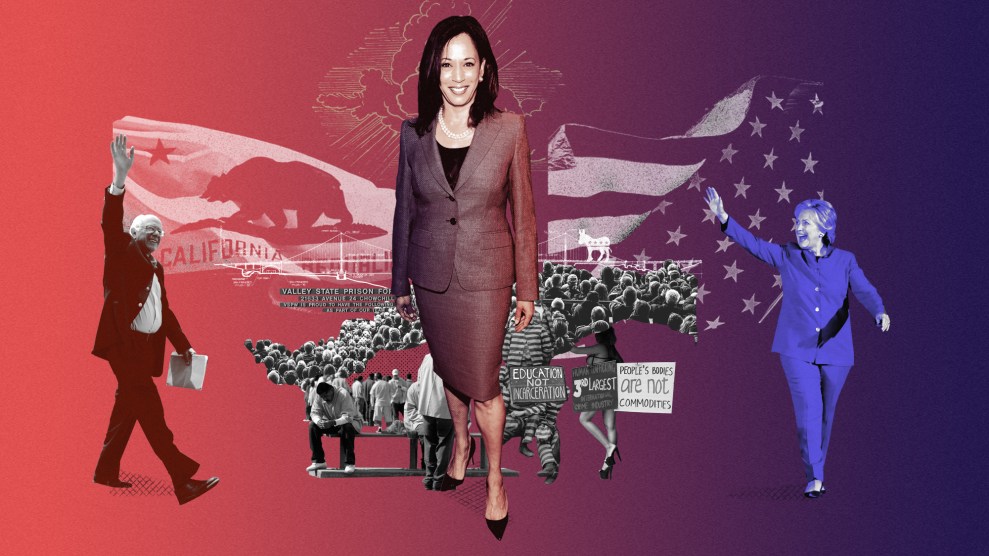

One reason that the nomination of Kamala Harris is so fascinating is that it comes at a time when we’re completely rethinking criminal justice in the United States. And Harris was a prosecutor. From her time as San Francisco district attorney and as California’s attorney general, critics argue that she locked up parents of truant children, left a potentially innocent man on death row, and didn’t support a measure mandating statewide standards for police body cameras. She caught a lot of flack over her criminal justice record during the Democratic primary, especially from the progressive wing of the party. Even so, Harris labels herself a “progressive prosecutor.”

She’s far from alone. But what does that label even really mean?

When Satana Deberry took the oath of office as district attorney of Durham County, North Carolina, in January 2019, it was a momentous occasion—for the city of Durham and for her, as a Black woman elected to an office historically held by white men, whose “tough on crime” policies have devastated communities of color for decades. She ran her campaign being vocal about the overpolicing of Black and Brown folks, promising sweeping reform. Now, more than a year into office, she faces the complicated realities of seeking to reform a deeply flawed criminal justice system and support a community ravaged by gun violence. She’s learning that implementing change will be harder than she could have anticipated.

We recently interviewed Deberry—who also stars in a new short film, I Am Not Going to Change 400 Years in Four, directed by Angela Tucker and Kristi Jacobson and produced by Chicken & Egg Pictures—as part of a broader examination of progressive prosecutors and how the office has become a focal point in the Republican-led culture war over criminal justice reform. (Just ask St. Louis’ first Black female circuit attorney, Kim Gardner, the prosecutor who recently charged RNC stars Mark and Patricia McCloskey, for more about that.) In our conversation, Deberry opened up about the challenges of tackling racial injustice and a pandemic in parenting teenagers; her sincere commitment to Converse sneakers; and the weight of being Black and progressive and also, at the end of the day, the one to put Black and Brown people in prison.

Read the full conversation between Mother Jones’ Jamilah King and Satana Deberry below. The transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

So I want to start with some big news. We are talking less than a day after Joe Biden announced Kamala Harris as his vice presidential running mate. Harris, of course, is a career prosecutor. What did you think when you heard that she got the nod?

I’m very excited for Kamala Harris as the vice president. I think she brings a wealth of experience and certainly a worldview that we’ve not seen before in that office. And so I’m excited for these next 90-something days to see how this campaign unfolds.

There’s been a lot of talk recently about progressive prosecutors. You describe yourself as one. So, what does it mean to be a progressive prosecutor?

For me, being a progressive prosecutor means that we are not just focused on the punishment part of prosecution—that first, we understand the communities that we are a part of, the historical nature of the offices that we hold, why those offices are the way they are; that we understand our communities and that we’re really focused more on accountability when we hurt each other, when we break our social contract, as opposed to punishment. And so we’re always looking at each individual case and trying to come up with a resolution that is both fair and just, that is equitable, that takes into account not just the rights of the defendants and the victims, but what we as a community values.

When you were elected, which reforms were at the top of your list?

Well, at the top of my list was to refocus the office from the steady stream of prosecution of low-level cases to the more serious cases in our jurisdiction, which I felt were being ignored. I felt like we were spending in our community a lot of time prosecuting people whose driver’s licenses were revoked, people who may have substance abuse problems or may be dealing with issues of poverty and mental health, as opposed to really focusing on the more serious crimes and accountability for those.

Is there a model for what you’re doing? Is there someone whose work has really inspired you to take this path?

We are always trying in this office to be fair and just. That is how we make every decision. And I think for me, I am both a student of history and sociology. I’m interested in the way that our communities have developed. And I’m also interested in the folks that come before me. So for me, my ideology is always, how do we get to freedom and how do we offer safety for the broadest number of people in our community, starting with those among us who have the least?

You are a Black, openly queer prosecutor in the South. Tell me what that’s like.

Mostly it’s like being overworked. I am in what many people would call a progressive community in the South. I think the South is not a monolithic place, to use an overused term; it is a very diverse place. It is certainly a very diverse place if you are a Black person. There are all types of Black people who live in the South, who are from the South, who were born here, raised here, who want to see it move forward. So for me, I think the most important things are that I am kind of from here, that I’m rooted in North Carolina. I grew up in North Carolina, this is my home. And so there’s a lot, I think, less attention on other issues. The most attention is on my policies and the work that we’re trying to do.

There’s been a refrain recently that Black women are uniquely qualified to lead because we’ve been leading behind the scenes for decades. Is that true for you?

Well, I am not new to any of this work. I’ve been practicing law half my life, and I’ve spent most of that time in advocacy roles. I’ve spent most of that time working for poor people, working for communities of color, and doing community economic development, affordable housing work, health equity work. And so I like to say that I had been doing administrative support for the movement for a long time. And I think at this point, we are seeing those Black women who have been doing the legal work, who’ve been doing the organizing work, step to the front and say, “Look, we have been doing this work. We uniquely understand the issues because we’ve been listening to people talk about these issues for decades, and we’ve been providing the services, and we now think that we should be in the policy arena making those changes.”

What’s been the toughest part of the job for you since you were elected and took office?

In criminal justice reform, we talk a lot about getting rid of prosecution of low-level crimes, of the over-prosecution of Black and Brown people, the over-prosecution of people who are poor, people with substance abuse problems, people that have mental health problems. The thing we don’t talk so much about is victims. The kind of dirty little secret of the criminal justice system is not only are all of the defendants Black and Brown, but all of the victims are also Black and Brown, and there are people out there whose status, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic class, the neighborhoods that they live in, subject them every day to being in some sort of danger.

The hardest part for me is balancing that work—making sure that we, while we are trying not to over-prosecute and only be focused on the violent and serious crimes, also lift up those people who are the most vulnerable and who are often people who look like me.

So a bit of a curve ball question: Tell me about the Converse, the Chucks. You wear them every day. Is it a statement? Is it just comfort? What’s going on there?

Well, it’s a couple of things. I have been a kind of weekend warrior, very poor athlete my whole life. And so I have knee issues and ankle issues and learned a while ago that Chucks helped me make it through today a little faster, but they’re also a style choice. I like them. They look good, they work with my suits, and they also kind of harken back a little bit to my roots in southeastern North Carolina. For folks who don’t know, the original Converse plant was located in southeastern North Carolina. And most of the people who worked there were Black and Indigenous people.

Whoa. I had no idea. That’s really fascinating. So you are also a parent. I can’t even imagine what it’s like to parent during this time. How’s it going being a Black parent right now, navigating your kids questions around race and, of course, the pandemic?

I have three teenage daughters. The oldest is a first-year college student, so we are managing not just the transition to adulthood, but the transition to adulthood during a pandemic, during a time when she’s very anxious about being on campus—just [thinking] how is she going to launch really? For those of us who went to college, this was one of the most exciting times of our lives. And so trying to parent her through not having that experience and having a fear-based experience is challenging.

I have two high school age children as well, one of whom styles herself as an activist. And so she has been out protesting, and was teargassed at a protest in May or in early June. She has been working all summer as a youth activist and organizing around issues of racial justice while still trying to figure out what AP classes to sign up for and how to pick a college during these times. So it’s been really challenging. It’s also been really challenging for the high schoolers because, interestingly enough, while being home has had a lot of challenges around schooling, it has also been a little bit of a respite from the racial microaggressions that they experience every day at school. So it’s been a little bit of a mixed blessing for them to be home.

Wow, there’s so much there. I want to go back to something you just said, which was that your daughter was teargassed at a protest. I imagine that was terrifying for you as a parent.

Yeah. She was there with her older sister and they had gotten separated and she called me crying, not so much because she was upset, but because she had tear gas in her eyes and she couldn’t find her sister. She’s 14. So for me, I had a lot of emotion around that, not just the individual fear of a parent, but what kind of society do we live in where now part of my child’s childhood is that she got tear gassed? Not that she was at the mall doing stupid things or hanging out with her friends at the movies, but that she had to be out in the streets protesting for her rights and for the rights of her people. What kind of society are we building where that is now part of the narrative of her childhood?

How do you think that will impact how you think about your role as a DA?

That’s a good question. I think, at some point—and my daughter and I have talked a little bit about this—we will probably, in our personal relationship, wrestle with what I do for a living. We are trying to be fair in this office. We’re trying to be just. We’re trying to be equitable. We’re trying to take the history of race in this country into account. We’re trying to offer diversions for prosecution and we’re trying to not give people records who don’t deserve records. And at the end of the day, I still put people in prison. And I still put mostly Black and Brown people in prison. And that was what my child was out there protesting against. So just like our country, at some point, we are going to have to reckon with that.

How does that make you feel? You say that at the end of the day, you put Black and Brown people in prison. What’s it like to shoulder that burden?

I mean, it is not inconsequential. I do think about that a lot. I think about that every day. I also see some pretty bad things as a prosecutor. I live in a jurisdiction that is small enough that I review every autopsy of every murder victim. I talk to the families of murder victims. I talk to the families of people who have experienced physical violence and sexual violence and sexual trauma, and for whom interaction with me represents the very worst day of their lives. And those are also generally Black and Brown people, right? And so something that is constantly on my mind and that I’m trying to balance is the compassion for the victims and the search for accountability for those people, as well as a protection of the rights of people who may be accused.

About the Filmmakers of I Am Not Going to Change 400 Years in Four

Angela Tucker and Kristi Jacobson teamed up to co-direct this powerful short documentary, a natural evolution of each of their bodies of work. Tucker is a New Orleans–based writer, director, and Emmy-nominated producer. Her latest films include Belly of the Beast, which will broadcast on PBS’s Independent Lens in fall 2020, and All Skinfolk, Ain’t Kinfolk (2020, PBS), a short about a mayoral election in New Orleans. Earlier films include narrative feature All Styles (2018, Amazon); Black Folk Don’t, a doc web series that was featured in Time magazine’s “10 Ideas That Are Changing Your Life”; and (A)sexual (2012, Netflix/Hulu). Jacobson is an Emmy-winning filmmaker, working as a director and producer of features, series, and short-form content. Some of her films include SOLITARY (2017, HBO), which takes an unprecedented look at life inside a supermax prison and is winner of an Emmy Award for Outstanding Investigative Documentary and Independent Spirit Truer Than Fiction Award nominee; Take Back the Harbor (2018, Discovery); A Place at the Table (2012, Magnolia Pictures/ Participant Media); and “Cartel Bank,” an episode of the hit Netflix original series Dirty Money (2018).