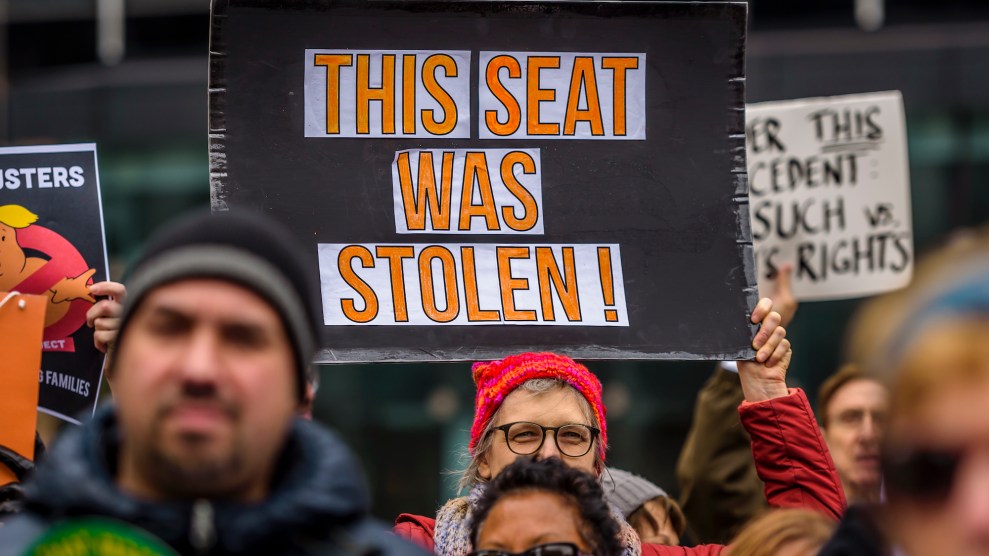

Progressive activists call on the Senate to demand opposition to his Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch.Erik McGregor/Sipa via AP Images

When news broke Friday evening that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had died, hardly an hour had passed before Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) announced his intentions to confirm her replacement before the end of President Donald Trump’s first—and perhaps last—term.

There’s a good chance McConnell will get his way: He controls the Senate’s agenda. There are 53 Republican senators, and in 2017, McConnell changed Senate rules to lower the threshold of votes required to end debate on a Supreme Court justice to a simple majority of 51.* And if he does succeed in putting a third Trump nominee on the court, the circumstances could be disastrous for would-be President Joe Biden, who would be facing a court stocked with justices hostile to the Affordable Care Act, abortion rights, gun restrictions, and COVID-19 precautions—in other words, everything on Biden’s wish list.

“Federal courts would have a Biden White House in handcuffs from day one,” predicts Aaron Belkin, an activist, academic, and co-founder of Take Back the Court. “In the very best case, the laws will be sharply curtailed. But more likely, they’ll just be struck down with very few exceptions.”

For the last few years, Belkin and his allies have been on a mission to remedy the deep partisanship by pushing Democrats, if and when they return to power, to expand the number of seats on the Supreme Court—a strategy called “court packing.” In the wake of Ginsburg’s death, they’ve doubled down on this idea, and some progressive Democratic lawmakers and candidates are joining them.

Court packing has been seen as a third rail in Democratic politics ever since President Franklin Delano Roosevelt proposed—and failed—to expand the court’s bench to 15 in the face of five sitting justices who sought to undercut his New Deal. But Democrats began to reconsider the idea after McConnell refused to hold confirmation proceedings for Merrick Garland, President Barack Obama’s nominee, on the premise that voters “should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice” and that the seat would remain vacant until a new president was seated. That break from precedent was just the first of many moves that have reshaped the federal judiciary in the GOP’s image during Trump’s first term. Trump has seated more life-appointed judges than all but one of his predecessors, according to a Brookings Institution analysis from January.

“Which party is trampling democratic norms—the one contemplating adding seats to the court to alter its makeup or the one that, in 2016, kept a seat open in order to deny President Barack Obama an appointment to the court?” my colleague Pema Levy wrote last spring. “The steps that Republicans have taken to shape the Supreme Court over the past few years have led some Democrats to believe that it’s time to throw out the rule book and fight back.”

That line of thinking entered the Democratic mainstream during the 2020 presidential primary. Eleven Democratic presidential candidates said they would be open to expanding the number of seats on the Supreme Court. Contenders like former South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) argued that doing so would be crucial for restoring the court’s legitimacy as a nonpartisan institution after the GOP’s success in politicizing it with its appointees.

Candidates for Congress have picked up the baton. Mondaire Jones, a Democratic candidate for Congress in New York’s 17th congressional district, has put court expansion at the center of his campaign platform. “Even before yesterday evening, it was abundantly clear that we have a partisan right-wing majority on the Supreme Court that is hostile to Democracy itself and the will of Congress,” Jones told me, citing the Supreme Court’s 2013 gutting of the Voting Rights Act, which was renewed with bipartisan support, as evidence.

Jones told me he plans to lead on the issue if he wins his seat, an all but assured outcome in his deep-blue district. He’s called on his Democratic colleagues to include court expansion in H.R. 1, their landmark democratic reform bill, which the party has signaled will be at the top of their agenda if Biden wins the White House next year. The need, Jones explains, is to protect every aspect of the Democratic agenda. “If we don’t deal with the issue of a partisan conservative majority in the Supreme Court by expanding the court, then we’re going to be back where we started,” he says.

Jones’ calls will likely be met with support from at least some progressive federal lawmakers. Marie Newman, a Democratic candidate for Illinois’ third congressional district—and similarly on track to win her seat—tweeted her support of expanding the court. So did Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.), chair of the House Judiciary Committee. On Friday night, Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) tweeted that he and his fellow Senate Democrats “must…expand the court” if they regain control of the Senate.

If Sen. McConnell and @SenateGOP were to force through a nominee during the lame duck session—before a new Senate and President can take office—then the incoming Senate should immediately move to expand the Supreme Court. 1/2 https://t.co/BDYQ0KVmJe

— Rep. Nadler (@RepJerryNadler) September 19, 2020

A majority of Democrats are on their side, according to a poll conducted by Data for Progress in May 2019. Belkin gave a briefing to Democratic congressional staffers on Supreme Court expansion last month. There’s a school of thought that even the threat of court packing under a Democratic-controlled Senate and White House might scare McConnell into not making good on his promise to confirm another Trump nominee.

So far, Biden has not signaled support for such a bold reform. Last year, he told Iowa Starting Line that he’s “not prepared to go on and try to pack the court, because we’ll live to rue that day.” (His campaign did not return a request for comment for this story.) Republicans have taken a hard line against court expansion, and moderate Democrats have feared that embracing the position might ultimately backfire. Earlier this year, Belkin and fellow political scientist James Drucker tried to assuage those concerns with research on swing-state voters that found “Republican and Independent voters are no more likely to vote, or to vote for a Republican candidate, if a Democratic candidate endorses court expansion.”

Biden has signaled a desire for an FDR-style presidency, premised on the sorts of sweeping reforms Roosevelt enacted to bring the country back from the brink of economic collapse and had also been derailed by a reactionary high court. “Pretty much everything in the progressive agenda will be vulnerable to the stolen courts,” Belkin warns. “Biden needs to realize that.”

*This article has been updated to clarify that Senate Republicans voted to change the threshold required to end debate on Supreme Court nominees, not the threshold required to confirm the nominees.