Thalia Tringo, a real estate agent in the Boston area, faces a dilemma whenever a homebuyer asks her if the local schools are any good. This can be a dicey topic because buyers’ perceptions of schools are often closely associated with the racial makeup of their student bodies, which usually matches the racial makeup of their surrounding neighborhoods. Tringo avoids answering specific questions about schools because of professional rules designed to prevent racial discrimination in housing. So like many real estate agents, she plays it safe, telling clients to look up the information on their own, even though she is wary of what they’re likely to find.

Among the first results on a cursory Google search is usually GreatSchools, a nonprofit site that ranks public schools nationwide and feeds that information to real estate sites such as Redfin, Zillow, and Realtor.com. GreatSchools is easy to find, but its ratings correlate closely with students’ racial or economic backgrounds. “The schools that get high marks and diverse schools tend to not be the same ones,” Tringo says of the exams GreatSchools uses to produce its score. She recalls going to an eighth grade graduation for a client’s kid at Winter Hill Community Innovation School in Somerville, just outside of Boston, and marveling at the friendly atmosphere among the middle schoolers and the diversity of the graduating class. “[It] was just amazing,” she says. “But you wouldn’t get that from looking at rankings.”

Winter Hill has one of the most diverse student bodies in Somerville: Half of its students are Latino and 13 percent are Black. Yet with a rating of 4 on a scale of 1 to 10, GreatSchools deems Winter Hill “below average.” Its students’ poor test scores drag its rating down, despite evidence that they’re making as much academic progress as most students in Massachusetts. Buyers looking for homes near highly rated schools might skip right over the Winter Hill neighborhood and look closer to one of Somerville’s other schools or in another town altogether.

There’s evidence that GreatSchools’ ratings are exacerbating racial segregation, not just within school systems but in the communities around them. “What makes GreatSchools popular is partly that they’re linked to real estate sites, which is partly what makes them dangerous,” says Sean Reardon, an education professor at Stanford University who studies poverty and inequality. “They start to overtly link people’s residential choices to what seems to be a measure of school quality. While that makes lots of sense if it’s a high-quality metric of school quality, if it’s more of a measure of socioeconomic composition of schools, then it runs the risk of creating incentives for more socioeconomic segregation.”

If you don’t have kids or haven’t been looking for a house recently, you may not have heard of GreatSchools, but its influence is profound. Its ratings are incorporated into popular real estate websites, which pay GreatSchools to use its data. It is supported by deep-pocketed philanthropies, especially ones with ties to the charter school movement. GreatSchools says its site attracts 45 million people a year; by comparison, there are about 40 million households with children in the United States.

Due to the pandemic and the reenergized movement to fight for racial justice, the inequities between school districts have been thrown into sharp relief: Some can easily afford to implement distance learning while others lack the resources to effectively teach online. Institutions of all sorts are being pushed to reexamine their roles in reinforcing systemic racial divides, and GreatSchools, which had already been reevaluating aspects of its school-rating metrics, appears to be doing the same. “Racial segregation and racist policies are woven into our education system and everyone involved has to do better to create more equitable outcomes for all students, GreatSchools included,” CEO Jon Deane told me in an email. But Deane added that he still believed GreatSchools can be an important tool for parents. “We feel strongly that it’s a parent’s civil right to have access to information about their schools.”

Bill Jackson got the idea for GreatSchools in the early 1990s, when San Francisco’s school superintendent wanted to know if a new restructuring program was working. He dispatched the twentysomething Jackson, who had a few years of teaching experience and a public affairs fellowship, to investigate. Jackson concluded that the rosy reports that principals were feeding back to the superintendent were mostly untrue. “This experience led me to believe that parents and the public—not to mention school administrators—needed more and better information about school quality,” Jackson later recalled.

In 1998, after working for a tech startup and a voter information website, Jackson launched GreatSchools. The nonprofit expanded rapidly after President George W. Bush signed No Child Left Behind four years later, requiring states to implement standardized testing and publish the results. GreatSchools quickly went from evaluating schools in two Bay Area counties to becoming a de facto grading system for all public schools. In 2011, as it added an unprecedented number of schools to its database, it brought in $10.8 million. (In 2018, the most recent year for which data is available, its revenues were $7.3 million.)

GreatSchools now maintains more than 100,000 school profiles, one for nearly every public school in the country. Its data, pulled from states and the federal government, includes test scores, teacher-to-student ratios, discipline rates, and students’ racial backgrounds. The site also includes user reviews from parents and community members, though their input doesn’t affect a school’s overall rating. GreatSchools lets schools add information to their profiles, including schedules, uniform policies, and what kinds of classes and extracurricular activities they offer.

But any nuance is overwhelmed by the single score featured prominently at the top of every profile. A rating of 1 to 4 indicates a school is “below average”; 5 or 6 signals it is “average”; and 7 to 10 means it is “above average.” Those scores are generated using complex formulas that rely heavily on standardized tests. Yet education researchers and advocates worry about evaluating schools based on their test scores. The tests, they say, measure surprisingly little of what students learn; have debatable abilities to predict kids’ future success; and produce results so highly correlated to students’ racial and economic backgrounds that they are, essentially, demography in disguise.

Since 2017, GreatSchools has tried to make its scores take into account whether students across demographic groups are falling behind their peers both within the same school and in the rest of their state. In August, GreatSchools rolled out a major overhaul of its system in California and Michigan, which produced new ratings that give less weight to raw test scores and more importance to equity and year-to-year improvements on test scores. GreatSchools plans to expand that approach nationwide. (Three days after this story was published online, GreatSchools announced that it was implementing the new ratings across the country.)*

But any radical changes to GreatSchools’ ratings would require states and the federal government to provide additional data for all schools in a consistent fashion. The appeal of GreatSchools ratings, after all, is that they provide a uniform way to compare schools across the country.

For now, GreatSchools’ heavy reliance on test scores—and other measures that are highly correlated with race, like graduation rates and Advanced Placement test performance—means homebuyers looking at its ratings don’t have to harbor any racial animus to steer clear of neighborhoods with sizable Black or Latino populations. They just have to use GreatSchools’ filters on real estate websites to skip over listings in areas with poorly rated schools. Since homebuyers who can afford to move into areas with highly rated schools are largely white and Asian, the scores could reinforce the separation of neighborhoods along racial lines.

In 2018, two business professors, Sharique Hasan of Duke University and Anuj Kumar of the University of Florida, published a study that examined what happened to neighborhoods in 19 states and Washington, DC, after GreatSchools ratings were introduced. Their analysis took into account local real estate trends and recognized that homes near schools with better test scores were already priced higher before GreatSchools rated them. When the researchers updated their findings this spring by adding seven more states, they found that the gap between average home prices near schools with better ratings increased by more than $16,300 after three years compared to those near average-rated schools. And those areas close to highly rated schools attracted more white and Asian residents. Near lower-rated schools, the gap in property values also decreased by roughly $16,000 over three years, and white and Asian residents left. “Broader access to information increased segregation because high-income families could more readily leverage school ratings to move to neighborhoods with better schools,” Hasan and Kumar wrote. “In this case, knowledge was indeed power, but only for the powerful.”

While residential segregation can lead to school segregation, the inverse is also true. A major reason for that is a 1974 Supreme Court ruling that school desegregation efforts cannot stretch across district lines, except in the most egregious cases. But even within districts, boundary lines that dictate which schools kids attend can skew neighborhood demographics. For decades, parents have used the racial breakdown of schools as a proxy for assessing their quality. Ann Owens, a sociology professor at the University of Southern California, found that households with children live in more segregated areas than those without children. “As long as neighborhoods are demarcated by school district boundaries limiting enrollment options, parents will take these boundaries into account when making residential choices, which may contribute to segregation,” she wrote.

Last year, journalists Matt Barnum and Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee of the education news site Chalkbeat concluded that GreatSchools’ ratings “effectively penalize” schools serving higher proportions of low-income, Black, and Latino students. The Chalkbeat writers noted that GreatSchools’ own data showed that many of these schools were doing a good job helping students learn math and English. Yet they still had a tough time getting above-average ratings on GreatSchools. “The result,” the reporters wrote, “is a ubiquitous, privately run school ratings system that is steering people toward whiter, more affluent schools.”

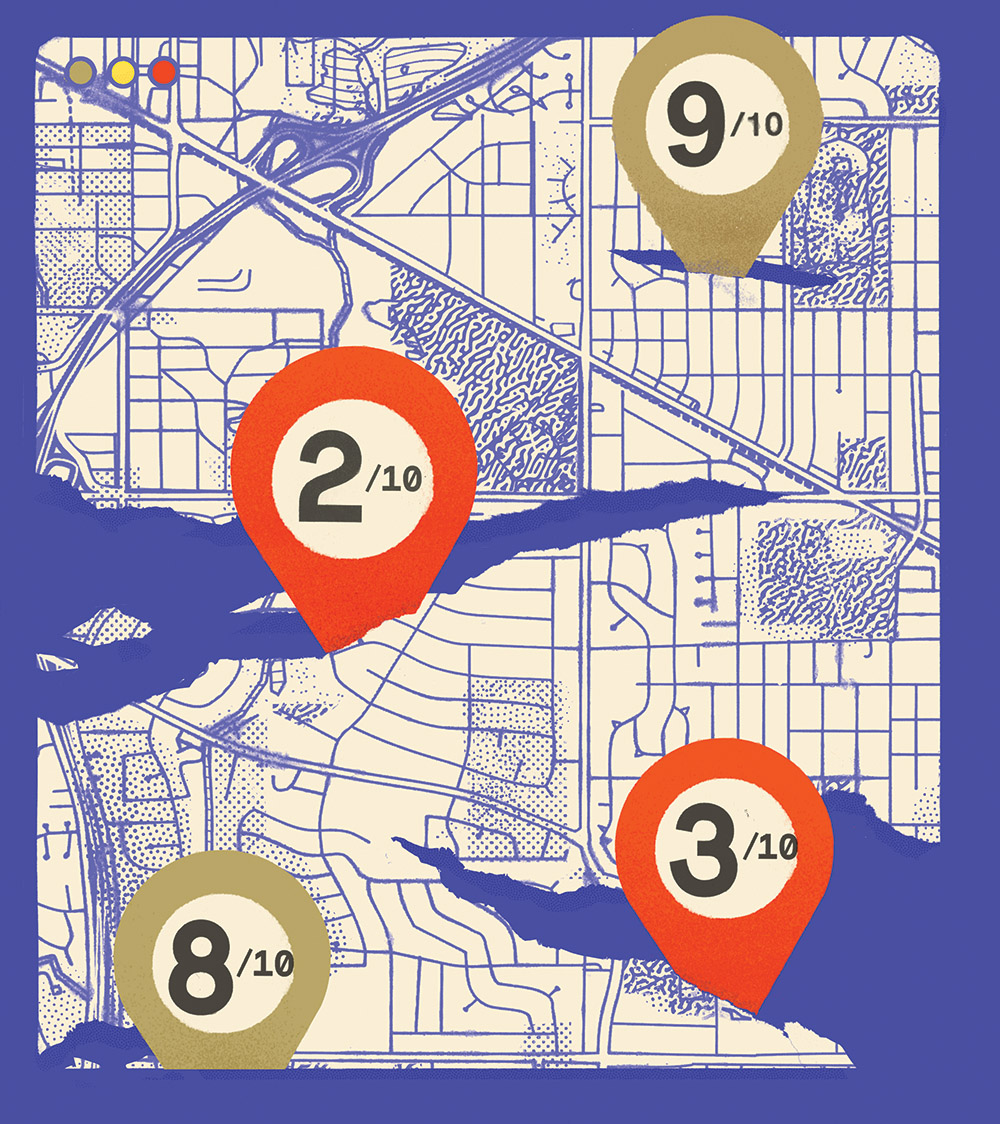

Explore Oakland’s GreatSchools Ratings in This Interactive Map

In Oakland, where GreatSchools is headquartered, most of the highest-rated schools (scores 7–9) are situated in the northern part of the city lining up with white neighborhoods, whereas most of the lowest-rated schools (scores 1–3) are concentrated in the neighborhoods of West Oakland, Fruitvale, and Eastern Oakland, parts of the city where Latino and Black people predominantly live.

GreatSchools says its ratings are not the final word on schools’ quality, but a starting point for parents to investigate further. But despite requests from Kumar, it won’t provide data on how many users scroll past the top number to read more nuanced information. Kumar says his study’s results fly in the face of hopes that equal access to information will promote equality, a premise that remains at the heart of GreatSchools’ mission. “I personally feel their intentions are noble,” he says. “But what we are seeing is, there are often unintended consequences.” Even if all parents had the same access to information, he says, they do not all have the same ability to put that information to use.

Deane, GreatSchools’ CEO, told me that the conclusions reached by Chalkbeat and Hasan and Kumar “overlook, or at best minimize,” the systemic racism that has “steered our society for decades.” “It’s very important to look at underlying issues and policies that segregate communities and create opportunity gaps, including school boundary designations, property taxes and the relationship to school funding, discipline and safety policies, among others,” Deane wrote in an email. “If we are to address the fundamental inequalities that still exist in America’s schools, we must respect the right of all parents to access critical information about their schools. This is GreatSchools’ mission.”

GreatSchools management has been aware of these issues for years. Jackson, who left the organization in 2016, says that as early as the mid-2000s, he and others at GreatSchools had worried that assigning school ratings could exacerbate residential segregation. “People are absolutely using [GreatSchools ratings] to find other people like them and to sort economically and sometimes racially,” he says. But he recalls that GreatSchools’ management concluded that self-sorting wouldn’t go away even if GreatSchools did. People would find the same information elsewhere, either from competitors or government websites.

It appears that internal conversations about these issues were limited. The group’s board never formally discussed them, Jackson says. Education writer Leanna Landsmann, who was on the board for 14 years and also served as the board chair, told me flatly, “I don’t remember any discussions ever about GreatSchools resegregating neighborhoods. Ever. I would have remembered that. I came out of the civil rights era.” Eric Hanushek, a prominent education researcher at Stanford University and former GreatSchools board member, says he remembers conversations about what kinds of families would use the site, but not about how ratings could affect residential segregation. (Several board members declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment.)

The way GreatSchools hopes people will use its rankings has shifted over the years. In 2011, the organization stated that “informed school choice” was one of its top missions. At the time, Jackson told me, charter schools and school choice had bipartisan support, and President Barack Obama’s administration promoted them as well. Now that charter schools have lost favor among Democratic leaders—largely because of concerns that they siphon resources from traditional schools and undermine teachers’ unions—GreatSchools has shied away from explicitly endorsing them.

Nevertheless, GreatSchools’ biggest donors read like a Who’s Who of the school choice movement: the Walton Family Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and Arnold Ventures. When I asked representatives of these organizations whether they thought GreatSchools helped boost the case for charter schools, they did not answer directly. “We are longtime supporters of the organization,” says Marc Sternberg, the Walton Family Foundation’s K–12 education program director, “because of our belief that knowledge is power, and the more clear, accessible information parents have about school options, the better.”

The Walton foundation has given GreatSchools more than $23 million since 2009. In 2011, the foundation’s $4.8 million grant made up almost half of GreatSchools’ revenue. The Gates Foundation, which has given $9.7 million to GreatSchools (most of it more than a decade ago), pointed out that its most recent grant supported an effort to track how high school graduates fare once they get to college. “Our investments in GreatSchools’ rating systems,” senior adviser Bill Tucker says, “are grounded in our belief that parents deserve and value information about how their schools are performing.”

Along with representatives from tech and finance firms, people with private and charter school backgrounds still feature prominently on GreatSchools’ board of directors. Deane, who became CEO in early 2019, has a long background in charter schools. He briefly worked on school issues at the Gates Foundation and spent three years as the director of education for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which has funded charter school programs. Earlier in his career, Deane worked as a math teacher and administrator in Bay Area charter schools. But he says he sends his children to a public school in San Francisco (it gets an 8 on GreatSchools). The organization, Deane says, is “agnostic” about what kind of school parents send their children to.

“Schools are not commodities that can be shopped for like cereal,” says Jack Schneider, an assistant professor of education at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, who has become one of GreatSchools’ fiercest critics. (The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has funded some of his research, too.) In 2017, he wrote a piece for the Washington Post castigating GreatSchools and the real estate websites that use its ratings. His daughter’s school in Somerville, he noted, received a 6 from GreatSchools while schools in nearby towns scored much better. “These towns, no doubt, have excellent schools,” he wrote. “But are they better than ours? There’s little evidence of that. The main difference, it seems, is that they are whiter and more affluent.”

The Boston area is a great illustration of how an overreliance on test-based evaluations can profoundly disrupt communities, whether it results in the state shutting down “underperforming” schools that serve Black and Latino students, or wealthy residents driving up suburban real estate prices as they look for the “right” school attendance zone.

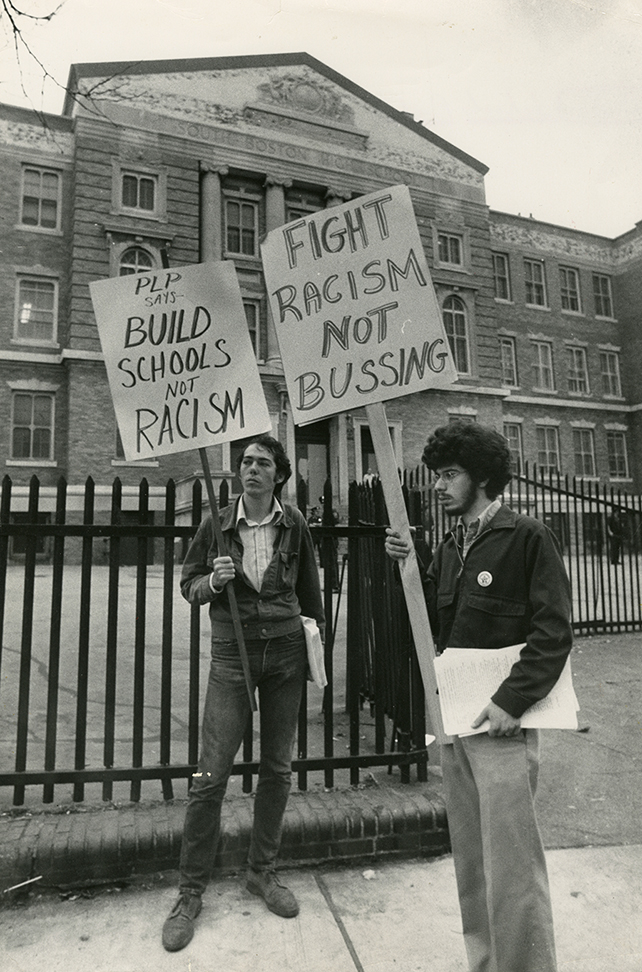

Boston City Councilor Louise Day Hicks, center, along with teachers from the William M. Trotter School, leads an anti-busing march on April 2, 1974.

Ted Dully/The Boston Globe/Getty

Two young men hold protest signs outside South Boston High School in Boston, on Sept. 12, 1974, the first day of school under the new busing system.

Dan Sheehan/The Boston Globe/Getty

School ratings are only one factor behind segregation in the Boston region. White racial animosity is so ingrained in the area that Stony Brook University professor of Africana Studies Zebulon Miletsky calls it “the Deep North.” That hostility exploded in the mid-1970s, after federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered about 17,000 Boston students to change schools in an effort to desegregate them. White parents clashed with police in front of TV cameras as the integration plan was carried out. The “anti-busing” protests had long-lasting effects: They weakened the resolve of Northern politicians to carry out the types of desegregation efforts Southern cities had gone through decades earlier, and they led to white flight from Boston to its suburbs.

The desegregation efforts ultimately did improve race relations in Boston, Miletsky says, but disputes about racial integration have flared up again. In 2014, Boston replaced the desegregation-era plan with one that prioritizes allowing children to go to nearby schools. Because of these changes, researchers have found that students in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods south of downtown now have fewer top-tier schools to choose from, face more competition to get into those schools, are less likely to attend them, and have to travel farther to get to them. The researchers pointed out that no students in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Mattapan lived within 1.5 miles of any of the district’s best-rated schools. Not a single one.

Ruby Reyes, the director of the Boston Education Justice Alliance, says test scores, which GreatSchools relies on for its assessments, set off a chain reaction that schools struggle to recover from. The cycle is exacerbated by gentrification that has pushed lower-income residents out of their neighborhoods or the city completely. At the same time, charter schools have poached students, particularly in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods, further draining public schools short of funds. The result is a “culture of fear and scarcity” in schools with low test scores. “It’s this vicious cycle of [schools] losing kids in enrollment and then their budgets get cut, and so services are lost,” Reyes says. “Then test scores go down and it becomes a ‘bad school,’ and nobody wants to send their kids to bad schools.”

Residents’ fears of sending kids to “bad” schools appear to be fueling “a growing mismatch between the demographics of kids who attend Boston’s K–12 public schools and the city overall,” the Boston Foundation reported in January. “The families who leave Boston when their kids approach kindergarten are predominantly middle and high income. Today, almost 8 in 10 students remaining in Boston’s public schools are low income…and almost 9 in 10 are students of color.”

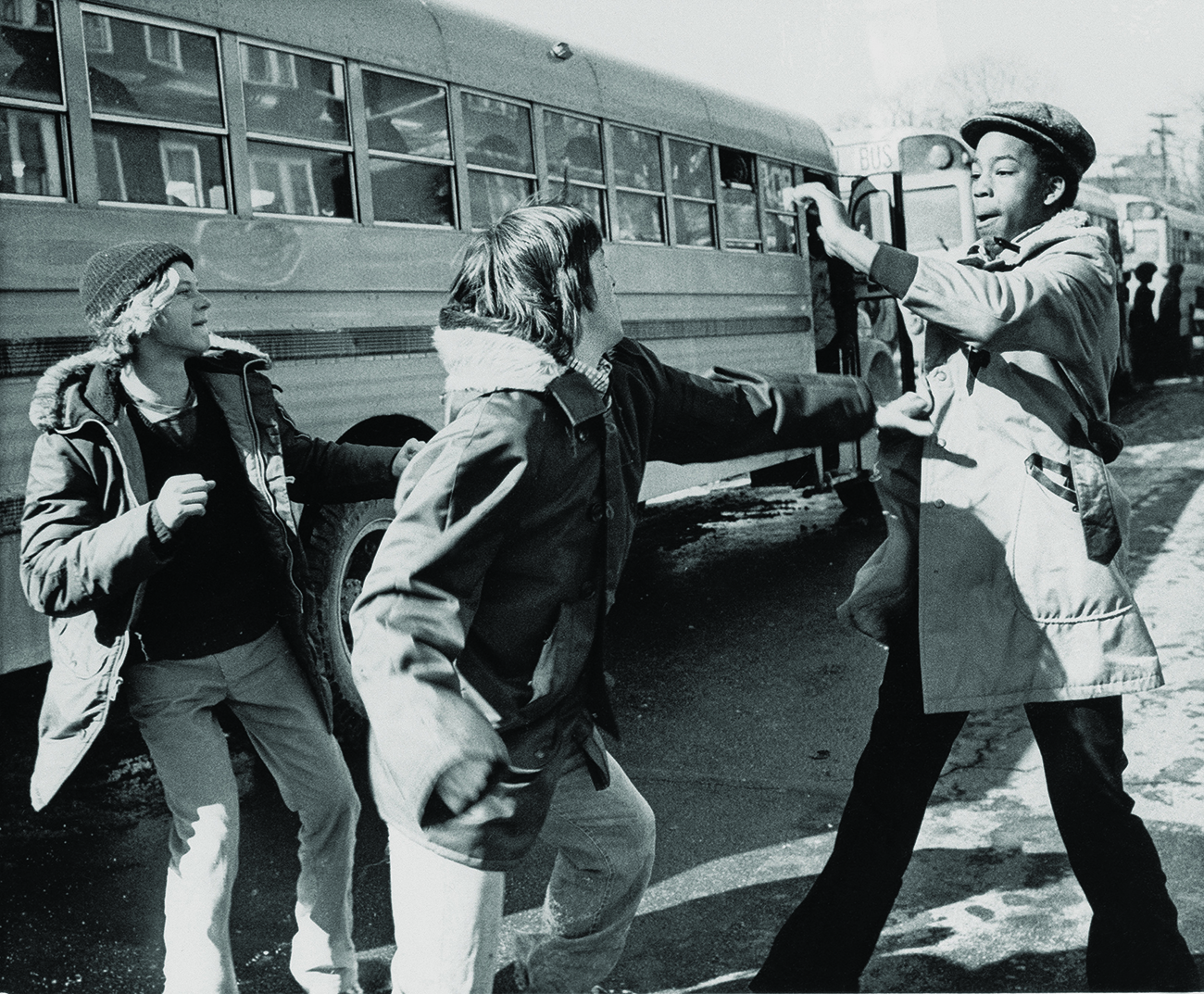

Fights between white and Black students broke out outside Hyde Park High School in Boston in February 1975.

AP Photo/DPG

Ultimately, Schneider says, families just want an easy way to assess the true quality of schools, and the simplified score GreatSchools offers doesn’t give much insight. “It’s not GreatSchools’ fault that the data wouldn’t answer that question for this family,” he says. “But if their theory of change is we should provide good information to people so that they can make decisions about where to send their kids, then you ought to ensure that you have the information that people need.” “Schools are not uniformly good or bad. Schools have different strengths and weaknesses.”

To find a better answer, Schneider partnered with eight school districts in the state to create an alternative. The Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment (MCIEA), which started in Somerville in 2016, now includes a range of districts, including Boston, wealthy suburbs, and outlying towns. It is developing its own evaluation system, for both schools and individual students, that is meant to replace standardized testing.

Most school rating systems don’t ask people what they actually want out of their schools, Schneider says. So that’s where he started. When he and other researchers talked to teachers, parents, administrators, local leaders, and students, they heard a list of concerns that aren’t reflected in GreatSchools’ ratings or the data that governments collect. For example, people said they wanted qualified teachers who connect with students and stick around long enough to be part of the community. They wanted rigorous curricula. They expected kids to feel safe so they can concentrate on learning. And they wanted a place where students could be well-rounded and engaged citizens.

One striking difference between Schneider’s school profiles and those of GreatSchools is that there’s no overall score for each school. “The fact that most states present [an overall] rating of schools is just absolutely evidence of malpractice,” he says.

But how do you gauge that without relying on standardized tests? I saw the alternative in action in an eighth grade science classroom in Milford early this year before schools were closed. The teacher broke her class into teams to assess the contents of four beakers containing clear liquid. The students had all sorts of ideas for how to do the test, or the “performance evaluation,” as MCIEA calls it. Some weighed the beakers to calculate the liquids’ density and compared their results to values they found on the internet. Several smelled the contents and noticed an odor suspiciously like vinegar. Two teams were at the back of the room, boiling the liquids over a burner. If there was any salt residue once the liquid evaporated, one of the students explained, that would probably mean it was salt water. Another kid asked for baking soda, presumably to see if it would foam up when poured in.

The students were devising their own experiments—and seemed to be thoroughly engaged even as they were being evaluated for their problem-solving and teamwork. Teachers in several MCIEA districts told me about the projects they’d been able to create thanks to the freedom they were given. A high school social studies teacher in Attleboro described a project that explored the controversy over whether Harriet Tubman should replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill. “I can remember a kid ranting about the Specie Circular,” the teacher told me excitedly. Sally Eosefow, a former engineer who now teaches math, rattled off several challenges she presented to her students. In one, precalculus students had to find a plane wreck on a map given just two angle measurements, which requires them to use sines and cosines. In another, kids chart their own pulse and blood pressure readings based on sinusoidal functions.

Students enter a school in South Boston on the first day of a court-ordered school desegregation program in September 1974.

Joe Dennehy/The Boston Globe/Getty

MCIEA’s long-term goal is to show that these methods produce more valuable results than the existing state exams, so that school districts could replace the tests completely. Yet first both the state and federal education departments would have to agree that MCIEA’s methods could produce the same results as standardized tests. Schneider says that would defeat the purpose, since he sees standardized tests as flawed to begin with. The consortium is “waiting for the political winds to turn” so it can replace standardized tests with its evaluation tools in the districts it works with.

If it succeeds, it could offer parents and educators a very different way of looking at school performance. “If we built better data systems that aligned with the things that people care about and that treated schools and communities fairly,” Schneider says, “maybe we would be able to unravel and unstitch this national narrative we have that good schools are a rare commodity that parents need to compete over and that you can’t just send your kid to the neighborhood public school.”

Explore Boston’s GreatSchools Ratings in This Interactive Map

In 2014, Boston replaced its desegregation plan with one that prioritizes allowing children to go to nearby schools. Since then, researchers have found that students in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods south of downtown have fewer high-performing schools to choose from, which is reflected in GreatSchools’ scores. For example, the Lilla G. Frederick Middle School in Dorchester gets a 1. Its student body is 1 percent white and the surrounding neighborhood is less than 3 percent white.

GreatSchools’ partners are showing signs of taking the problem of racial segregation and school ratings more seriously. Redfin recently changed how it displays GreatSchools ratings. Glenn Kelman, Redfin’s CEO, tells me that putting the ratings on home profiles has been a “real point of contention here at the company.”

Kelman says his employees worry about the potential to encourage white flight and exacerbate residential segregation. Plus, as a company that employs real estate agents, it has to worry about their running afoul of fair housing laws. “The challenge that GreatSchools and Redfin have is that the consumer does want a really simple answer, and we want to provide context,” Kelman says. “People want to know which one is good and which one is bad. When you try to say it’s more complicated than that, you sometimes lose your grip on their attention.”

Kelman says an intern confronted him two years ago about how reductive the GreatSchools ratings could be, so he contacted GreatSchools about providing more details on Redfin’s website. GreatSchools, Kelman says, jumped at the opportunity. Now users can click on a school listed on a house profile and see the different components of GreatSchools’ ratings as well as residents’ reviews of the school. In its first year, the new feature didn’t lead to any changes in consumer behavior, according to Redfin. (Only 10 to 15 percent of people who click on a home profile scroll down far enough to see school ratings in the first place, the company says. It could not provide data on how many users filtered their search results by school ratings, but said few people use the feature.)

Still, Kelman says he’s glad his site included the new information. “I think tech, more broadly than Redfin, is just waking up to the idea that websites matter, mobile applications matter. We have to be careful about the information that we provide,” he says.

“Being in this seat a long time and trying to influence where people ought to want to live, what kind of home they ought to want for environmental reasons or for reasons of social justice, I just feel like I’ve come up against the most deep-seated desires people have,” Kelman tells me. “They call us when they just had their first baby and their world has narrowed to those two or three people—one or two parents and the child. Trying to get them to think about the rest of an American city is hard.”

This story was published with the support of a fellowship from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights.

This story has been updated to reflect GreatSchools change to its rating system.