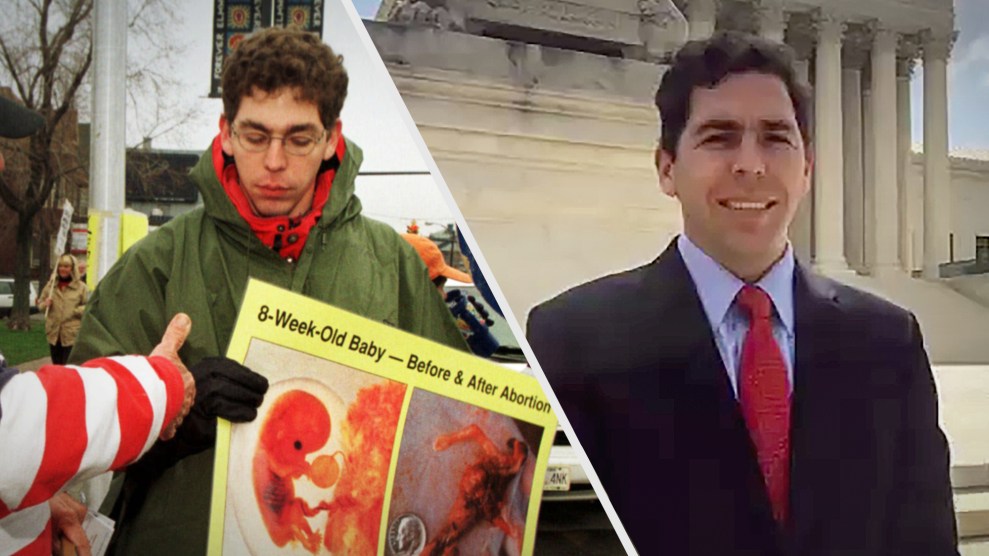

Mother Jones illustration; Jim Loscalzo/CNP/Zuma; Getty

Alliance Defending Freedom is the nation’s largest and most influential anti-LGBTQ legal organization. With a budget of more than $50 million and more than 40 staff lawyers, it has participated in nearly 60 successful US Supreme Court cases since it launched in 1994. Among them were some of the most high-profile legal battles in the culture wars, where ADF has opposed same-sex marriage and defended anti-LGBTQ discrimination. Its founder, Alan Sears, explained in 2012 speech to the far-right, anti-gay World Congress of Families, “In the course of the now hundreds of cases the Alliance Defense Fund has now fought involving this homosexual agenda, one thing is certain: There is no room for compromise with those who would call evil ‘good.’”

Before President Trump nominated her for a seat in the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2017, Notre Dame law professor Amy Coney Barrett taught a class at five different sessions of the ADF’s summer-long law student training program in Phoenix and Alexandria, Virginia. Known as the Blackstone Legal Fellowship, the program was designed to teach students “how God can use them as judges, law professors and practicing attorneys to help keep the door open for the spread of the Gospel in America.” It’s part of ADF’s long-running effort to seed all levels of public life with Christian legal warriors by training top students and placing them in prestigious internships or clerkships where they can advance the group’s larger religious agenda.

Since 2000, more than 2,400 students have gone through the program and many have gone on to influential government positions. Just one example: Matthew Bowman, an anti-abortion zealot who was in the Blackstone fellowship while a student at Ave Maria law school. In 2017, President Trump appointed him deputy general counsel to the Department of Health and Human Services. He is now principal advisor to the director of the HHS Office of Civil Rights, which this year attempted to strip the anti-discrimination protections for LBGT people out of the Affordable Care Act.

Yet when Sen. Al Franken (D-MN) asked Barrett about her work for ADF during her 2017 confirmation hearing, she claimed to have no idea that ADF had an anti-LBGT agenda when she agreed to speak there. She testified that she’d only recently learned that the Southern Poverty Law Center had described ADF as a hate group for supporting the criminalization of homosexuality overseas and also for the “recriminalization of homosexuality in the United States.”

“This is a group that fights against equal treatment of LGBT people,” Franken informed her. “This is a group which calls for the sterilization of transgender people abroad.”

“I was not aware of that,” Barrett replied. “I’m invited to give a lot of talks as a law professor. I don’t know what all of ADF’s policy positions are. And it has never been my practice to investigate all of the policy positions of a group that invites me to speak.”

Franken resigned from Congress amid sexual misconduct allegations in 2018, but he wasn’t the only person skeptical of Barrett’s testimony. “That answer suggests either she’s stunningly unobservant or not fully truthful,” says Jenny Pizer, who has litigated for two decades against ADF and is senior counsel at Lambda Legal, an LGBTQ civil rights group. “It’s truly incomprehensible that somebody who’s a conservative legal scholar with a focus on religion and very active in the very conservative religious legal movement would be unaware of ADF’s priorities.” ADF did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Barrett’s 2017 testimony regarding ADF takes on new relevance as she prepares to appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee Monday for a new round of hearings, this time for a lifetime seat on the Supreme Court. It raises questions not just about whether she might have previously lied to Congress, but whether she might also lack some of the basic critical faculties usually expected in a lawyer ascending to the nation’s highest court.

Indeed, there were plenty of signs at Blackstone that might have tipped off even the dimmest of lawyers to ADF’s anti-LGBTQ agenda during the five times Barrett spoke there. Let’s just start with the most obvious: Blackstone’s reading list. During some of the years Barrett taught, students’ reading lists included a book written by Sears called The Homosexual Agenda: Exposing the Principal Threat to Religious Freedom Today. You’d have to be living under a rock, or perhaps in a secretive charismatic Christian community, not to appreciate that the title alone indicates how ADF views LGBTQ people.

Then there’s the “lexicon” of language that ADF sent to faculty members and asked them to adhere to when they participated in the Blackstone program. Unearthed by journalist Sarah Posner for Type Investigations, the lexicon instructed faculty to excise the word “gay” from their vocabulary, and to instead use “homosexual behavior” because, according to a note from Sears, “Homosexuality is a personal struggle.” “Sexual orientation” should instead be called “sexual preference/choice,” and transgender should be replaced with “cross-dressing” or “sexually confused.” Faculty should refer to same-sex marriage as “marriage imitation.” The lexicon stresses the use of “homosexual agenda” rather than “lesbian and gay civil rights movement” because, a note says, “The goals and the agenda of advocates of homosexual behavior are not ‘rights,’ but ‘demands.’” The lexicon insists on scare quotes around the “hate” in hate crimes and replaces the term “bigotry” with “defending biblical, religious principles.”

Maybe the mother of seven was too busy giving talks to the Federalist Society—the conservative legal group pushing her Supreme Court nomination—to read all the materials in preparation for her years of speaking at Blackstone. But if the lexicon didn’t clue Barrett in about the views of her employer, her colleagues on the faculty certainly could have enlightened her. Over the years, Blackstone has drawn speakers from the country’s most prominent Christian anti-LGBTQ groups such as James Dobson’s Focus on the Family, whose leaders helped create ADF, and the Family Research Council, headed by Tony Perkins, a man who has long equated homosexuality with pedophilia and warned that gay men pose a dire threat to children.

The past faculty list is a who’s who in the fight against marriage equality, notably John Eastman, who headed the anti-LGBTQ National Organization for Marriage. And there was Kyle Duncan, an attorney who spent most of his career fighting marriage equality, and later, defending “bathroom bills” and other measures designed to discriminate against transgender people. (President Trump appointed Duncan to a seat on the 5th Circuit in 2018.) The faculty list also makes clear that ADF was unlikely to have invited Barrett to join it if there was any indication that she disagreed with its core values. (“I’ve never been invited,” Pizer says with a laugh.)

But Barrett declared during her confirmation hearing that she was shocked anyone would suggest the program might promote anti-gay discrimination. In her years at Blackstone, she insisted she never encountered anything even bordering on anti-LGBTQ bigotry. “I never witnessed any discriminatory conduct in any way,” she said. “I never had a whiff of that. My presentation was about constitutional interpretation. It had nothing to do with those topics.”

In follow-up questions after the hearing, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) pressed Barrett further about her work for ADF. “You explained that you were unaware of the program’s discriminatory conduct at the time you made your speech,” he wrote. “If you had known of the program’s support for anti-gay policies, would you have still provided the speech?” Again, Barrett—who spoke not once but five times at the group’s program—pleaded ignorance. She said she still had not investigated whether SPLC had accurately described ADF’s anti-gay policy positions. Of course, she did know enough about it to suggest to Whitehouse that SPLC’s designation of ADF as a hate group was “controversial.” Barrett told Whitehouse, “For my part, I would not participate in any program that advocated hatred and discrimination against any group, including LGBTQ persons.” She was confirmed to the seat 55–43, checking yet another box in her glide path to the Supreme Court.

There’s yet another reason why Barrett likely knew that anti-LGBTQ discrimination was at the heart of ADF’s agenda when she first agreed to speak at Blackstone and continued to help train its burgeoning legal army: ADF was behind some of the most interesting, contentious, and controversial Supreme Court cases of the 21st Century. Many if not most of them involved LGBTQ civil rights. In short, they were precisely the sorts of cases Barrett was supposed to be analyzing and researching during her 15 years teaching constitutional law at Notre Dame before the confirmation—another reason why her 2017 testimony is so utterly unconvincing.

ADF “files dozens of cases in state and federal courts every year and works hard to boost its public profile,” says Rob Boston, senior adviser at Americans United for Separation of Church and State, who has followed ADF’s work for years. “It’s inconceivable that anyone who moves even tangentially in conservative legal circles would not know of this group or its agenda.”

Last month, when Trump announced he was tapping Barrett to replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, he said he was nominating “one of our nation’s most brilliant and gifted legal minds to the Supreme Court. She is a woman of unparalleled achievement, towering intellect.” Is it really possible, then, that in her five years of teaching at Blackstone she had no idea that ADF was, for instance, the force behind Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission?

That’s the case in which ADF successfully represented a Colorado baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. Originally filed in 2012, the baker’s case was covered extensively in the media as it worked its way to the Supreme Court, which in 2018 ruled in the baker’s favor on narrow procedural grounds. “If she had been unaware of it, one has to wonder how she was doing her scholarly work,” says Pizer. “That type of work requires looking at the world around you and teaching about what’s going on.”

Or how about the protracted and very public litigation over Proposition 8, the 2008 California ballot initiative that banned same-sex marriage in the liberal state? Is there any conceivable way Barrett failed to notice Hollingsworth v. Perry, the Supreme Court case that wouldn’t exist but for the Christian law firm? In 2009, when activists sued the state to overturn Prop 8, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and later, state attorney general Kamala Harris, refused to defend the law in court. So ADF stepped in to do the state’s job.

Representing the official sponsors of the ballot initiative, ADF fought the case all the way to the Supreme Court, which in 2013, ruled that ADF’s clients did not have standing to bring the case and dismissed it. The decision effectively legalized same-sex marriage in California two years before the court made it legal nationwide in its decision in Obergerfell v. Hodges. This is yet another case with which ADF was intimately involved, and which conservative Supreme Court justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas have been railing against in opinions ever since.

For years, these cases were hot topics in the media, which invariably highlighted ADF’s role, and on virtually every legal talk circuit. They involved both a fair amount of anti-LGBTQ bigotry but also pathbreaking constitutional interpretation—the very subject Barrett was teaching at Blackstone and supposedly studying and teaching as a legal scholar at Notre Dame.

Pressed in 2017 by Franken to explain her professed ignorance of ADF’s anti-LGBTQ bent, Barrett went all wide-eyed ingenue. She claimed ADF could not possibly be a hate group because it was working on a case with lawyers from the white-shoe law firm WilmerHale, “one of the most reputable and esteemed law firms in the country, and they wouldn’t be co-counsel with ADF if it were a hate group.” An incredulous Franken replied, “So is it your position that no hate group has ever filed or co-filed a brief to the Supreme Court?”

“I haven’t researched that question,” she demurred.

Franken suggested that her lack of curiosity about the group hiring her to speak might indicate bad judgement, a problem for someone hoping to become a judge. “Is it your habit of accepting money from organizations without first learning what they do?” he asked.

“If I were invited to speak by Pol Pot or by the KKK or a group like that, I would certainly decline the invitation,” she responded, insisting she’d never speak to a hate group.

“Well, sounds like the ADF is something of a hate group, doesn’t it?” Franken asked before moving on.

It’s hard to watch Barrett’s performance during her 2017 confirmation hearing and come away without thinking either she was lying or is a shockingly clueless lawyer. But there is another possible interpretation: Barrett simply doesn’t consider what ADF does as discriminatory or hateful, but rather sees it as the righteous moral work of “defending biblical principles,” as the ADF website suggests. Her inability to see how LBGT people might perceive that work quite differently suggests a form of tunnel vision that even some of the conservatives on the Supreme Court don’t have, particularly Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, who this summer wrote the majority opinion in a landmark case, finding that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects gay and transgender workers from discrimination.

“She was asking the senators to believe the unbelievable,” Pizer says. “I’m not going to accuse her of lying to their faces, but given the factual record, it’s very hard to believe [her testimony]. That poses a question for all of us about that process. There’s no way to look at it and feel comforted.”