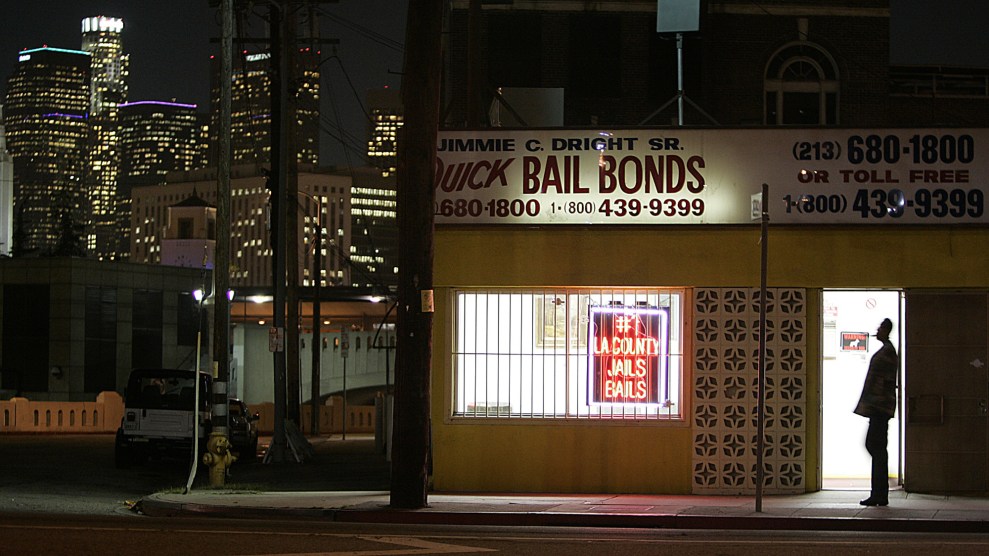

A Los Angeles bail bonds company across from street from the Men's Central Jail.Robert Gauthier/ Los Angeles Times/ Getty Images

In early December, when George Gascón was sworn in as Los Angeles County’s new district attorney, one public defender said it felt like a “weight had been lifted off of their shoulders.” Gascón, a former Los Angeles beat cop, is an unlikely reformer for the largest prosecutor’s office in the country—which filters defendants into the largest jail system in the world. But within the growing ranks of progressive prosecutors, Gascón is carving out a reputation for moving fast.

His first two weeks in office sent shockwaves across Los Angeles: in a series of special directives, Gascón announced that Los Angeles prosecutors will no longer seek cash bail, sentencing enhancements, or capital punishment. His transition team, which includes just one prosecutor, is composed of community advocates, bail experts, and people with lived experience in the justice system. In his first public meeting as DA, he met with Black Lives Matter activists and family members of people shot by LAPD, promising to reopen police shooting cases that were closed by his predecessor.

“Whether you were a protestor, police officer, or prosecutor, I ask that you walk with me,” Gascón said in his inauguration speech. “Join me on this journey.”

Not everyone has. Gascón’s former union, the Los Angeles Police Protective League—which spent at least $1 million to oppose his candidacy—is furious. So are some rank-and-file district attorneys. Multiple Los Angeles public defenders told Mother Jones that those prosecutors, along with tough-on-crime judges, are fighting implementation of Gascón’s directives every step of the way.

Take Gasón’s elimination of cash bail. The directive, which went into effect in early December, has the potential to address longstanding racial and economic disparities in Los Angeles County’s jails, where pretrial detainees make up some 44 percent of people incarcerated—many because they don’t have the money to make bail. The rule change covers all misdemeanors and non-serious or non-violent felony charges, except in instances when a defendant poses a threat to public safety or is a flight risk.

One attorney in the public defender’s office hopes that Gascón’s decision to end cash bail will alleviate overcrowding, curb COVID exposure, and ultimately slow down what she sees as an “assembly-line” approach to justice. The attorney especially fears for one of her younger clients facing felony charges. The client has sickle cell anemia and has had to quarantine in jail. Now, they may be eligible for release without bail. “I also feel like it shouldn’t be a life sentence with dying from COVID either,” she says. “That’s scary.”

But speaking on condition of anonymity, four Los Angeles public defenders told Mother Jones that Gascón’s directive is meeting a wave of pushback from both prosecutors and judges.

One public defender says that, despite the directive, a judge kept her client, who faced non-violent, non-serious felony charges, incarcerated with bail that had been reduced to $150,000—although both she and the prosecutor argued that the client should be released on his own recognizance. The following day, the attorney said, the judge cited public safety grounds to raise his bail back to the $560,000 dictated by California’s bail schedule.

“I argued that she needs to consider my client’s financial situation,” the attorney says. “This may as well be a no-bail, because he can’t pay it. She wouldn’t budge.”

Another attorney says that deputy prosecutors have mounted their own challenges to Gascón’s bail order. Even as prosecutors give the directive lip service, reading from the directive to ask for a dismissal, she says she’s witnessed them telling the judges, after their argument, that they believe the directive to be “unethical.”

“They’re making it well known that they’re not about the bail policy,” she says.

Gascón’s sentencing enhancement directive has faced similar backlash. Last week, high-profile deputy DA Richard Ceballos refused to tell a judge in a case he was prosecuting that dismissing hate crime enhancements would serve the interest of justice; the Los Angeles Times reported that the judge in the case “ultimately blocked the motion to dismiss.” Another judge said prosecutors had “no independent authority” to dismiss an enhancement in a felony case, “drawing a cheer from two LAPD detectives sitting in the back of the courtroom.”

On Friday, Gascón walked back part of his sentencing enhancement ban. Now prosecutors can seek additional prison time for charges of hate crimes, elder or child abuse, and sex trafficking.

A memo obtained by the Los Angeles Times revealed that Gascón is now ordering prosecutors to notify their supervisors when a judge refuses to dismiss an enhancement. In addition, a recent Google document—now taken down—circulated among public defenders to track “non-compliant” deputy prosecutors. Both the public defender’s office and Gascón’s transition team denied creating or sharing the file.

Despite the hurdles, reform experts say Gascon has plenty of time to reshape the office. “At the end of the day, prosecutors are just one part of this puzzle,” says Robin Steinberg, a bail expert on Gascón’s transition team. (Disclosure: Steinberg is CEO of the Bail Project, where I worked from the end of 2017 to June 2019.) “Judges are going to have discretion over what they do with respect to bail and whether they hold somebody pretrial or not, and in the end, the police are the ones who make decisions about who they arrest.”

“I think that’s just a culture change that’s going to take a while,” says Alicia Virani, who directs the criminal justice program at the University of California, Los Angeles. “It’s going to take [Gascón] recruiting DAs who have a more similar mindset, to make sure that these policies can actually be effective.”

Lex Steppling, director of campaigns and policy for advocacy group Dignity and Power Now, says that any reform is difficult to implement without judicial accountability. Steppling’s organization is at work on a countywide bill that would establish an independent, community-based pretrial services agency, ban risk assessments, require the county to finance restrictive release tools like ankle monitors, and, ultimately, allow most people in pretrial detention to return home.

“We obviously don’t believe that our salvation or liberation lives inside the district attorney’s office,” Steppling says. “But the goal is to have more people home, back in our community and safer. And much of what he plans to do will help with that.”