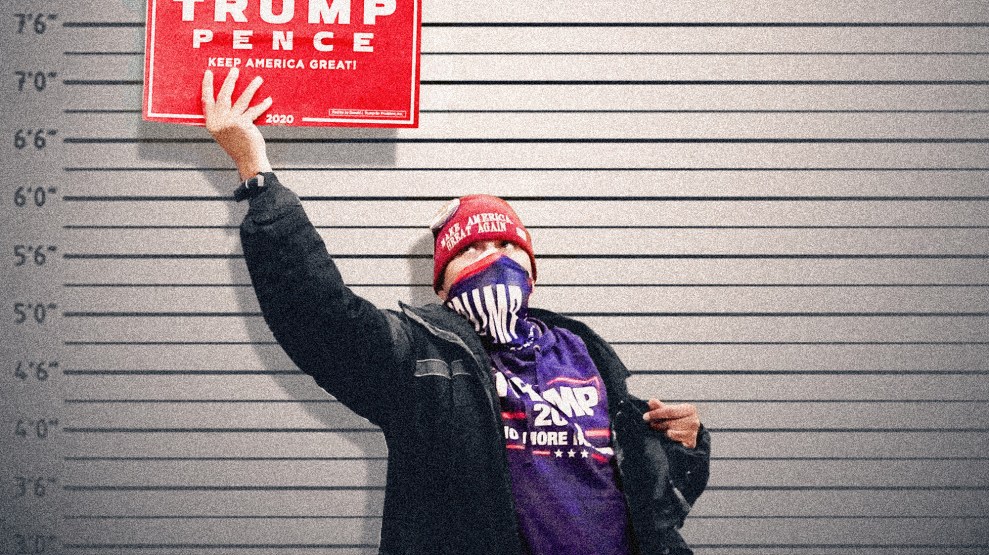

Supporters loyal to President Donald Trump clash with authorities before successfully breaching the Capitol building during a riot.John Minchillo/AP

In the hours after a mob of pro-Trump insurrectionists stormed the Capitol on January 6, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary tweeted that its top searches included “coup d’état,” “putsch,” and “treason.” On the top of the search list, however, was the word “sedition,” which Webster’s defines as “incitement of resistance to or insurrection against lawful authority.”

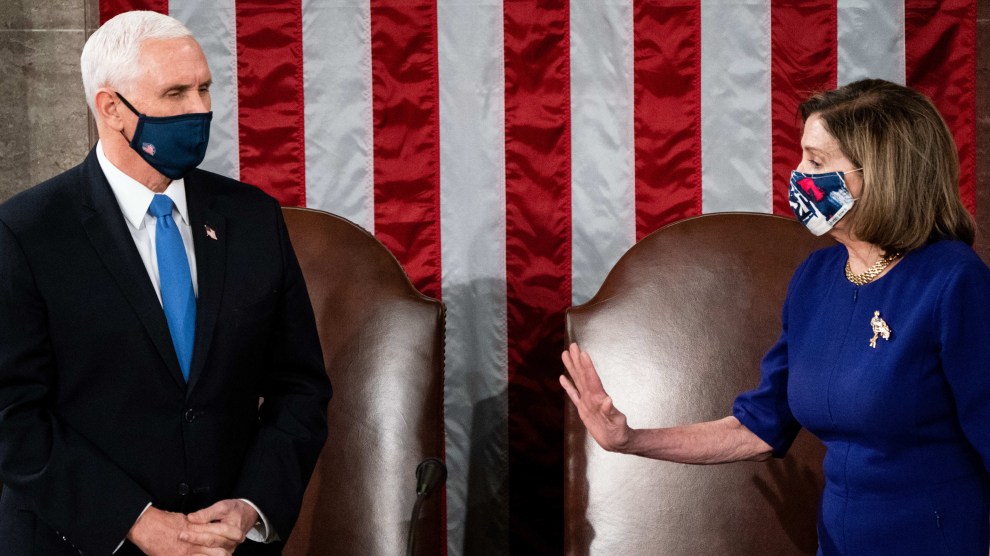

The word appeared frequently during the period after the violent attack that left five people dead. President-elect Joe Biden said their action “borders on sedition.” During a press conference the following day, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi condemned President Trump for “calling for this seditious act.” The word has appeared in the headlines of innumerable op-eds, calling for the “Seditious Republicans” who objected to the certification of the electoral college votes to be held accountable for inciting the deadly riot. Some scholars have even argued the article of impeachment introduced by House Democrats should explicitly link Trump to the federal crime of “seditious conspiracy.”

But seditious conspiracy is a very specific crime, which the US criminal code defines as two or more people conspiring to “overthrow, put down, or to destroy” the government, “prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law,” or “seize, take, or possess any property of the United States” by force. It is punishable by up to 20 years in prison. In a case from 2010, members of a militia group in Michigan were accused of planning to kill law enforcement and engage in armed conflict, but were latter acquitted of sedition charges.

In order to more fully understand this concept that has gained so much currency recently, Mother Jones spoke to Geoffrey Stone, a constitutional law scholar at the University of Chicago. He’s also the author of several books, including Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime, From the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terror, which explores the history of free speech during wartime. We caught up with him to discuss the term and its relevance to recent events.

Let’s start with the basics: What does “sedition” actually mean?

Acts of sedition are designed to overthrow or to prevent the functioning of the government. A simple example would be if the people who entered the Capitol last Wednesday had the intent to prevent the government from proceeding in the way it was planned. Most of the issues in American history about sedition have involved seditious libel, when you can punish someone for speech that might have the effect of leading others to engage in illegal actions.

When did the concept of “seditious libel” first appear in American history?

The “Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798″ were passed during one of the dark periods in American history. Their purpose was to prevent criticism of the government. If you gave a speech in which you criticized the president, John Adams, that could be regarded and was regarded as seditious libel, you could be criminally prosecuted. The rationale was that there was the possibility that we would go to war with France, and that speech critical of the administration would potentially undermine the ability to do that successfully. More than a dozen people, including journalists and public officials, were prosecuted by the Adams administration. As it turned out, we never went to war and Adams was defeated by Thomas Jefferson in the election of 1800. In part, this was because people were unhappy with the Sedition Act. Since 1969, no one has been convicted in the Supreme Court of the crime of engaging in speech that could lead others to engage in unlawful conduct. The test is so demanding that it’s almost impossible to satisfy.

How has the term and what it evokes evolved over time?

The next major period in which this was an issue was World War I. [Woodrow] Wilson, having decided to go into war, wanted speech critical of this decision silenced because he wanted people to buy war bonds, to enlist in the military, and to be willing to accede to the draft. The Espionage Act of 1917 was adopted. Then, a year later, Congress enacted the Sedition Act of 1918 and people who criticized the war or the draft were routinely prosecuted and sentenced to prison from 10 to 20 years. Over the next century, the nation faced these questions on a number of occasions, most dramatically during the McCarthy era. In 1969, in a case called Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Supreme Court expressly held that an individual could not, consistent with the First Amendment, be held liable for speech that might cause others to engage in illegal conduct, unless they specifically intended to cause others to engage in illegal conduct, and unless that illegal conduct was likely, imminent, and grave.

So it might not be enough to say “let’s storm the Capitol,” for instance?

One ambiguity that exists to this day is whether the speaker not only has to specifically intend to create a likely and imminent danger of grave harm, but also has to expressly advocate unlawful conduct. If someone said “storm the Capitol” with a specific intent of causing individuals to go to the Capitol immediately, and with the intent and the understanding that that was likely to happen imminently, that would be punishable.

Some have argued that the crimes committed by protesters on Wednesday do fit the definition of seditious conspiracy under the penal code. What’s your take on that?

If you protested outside the Capitol, within the appropriate bounds of free speech, you couldn’t be punished. The protesters who actually entered the Capitol can certainly be punished because what they did was not speech. So they don’t have any First Amendment defense if they actually violated the law by trespassing onto the Capitol in order to disrupt the ordinary workings of government. That goes beyond the First Amendment and could fairly be characterized as unlawful and seditious conduct.

Could one argue that President Trump himself committed that crime?

In terms of Trump, there are three questions that one has to ask: First, did he expressly advocate the unlawful conduct that occurred? Second, did he have the specific intent to cause what happened, or was he just calling on people to engage in legal protest? That depends on complex evidence about what his goal was and about what he literally said. And third, there’s the question of “likely and imminent.” I have no doubt that the “grave harm” part of the test would be satisfied by what happened. The speech that took place right before they went to the Capitol would satisfy the imminent issue. But was it likely that they would invade the Capitol rather than simply protest? That’s a factual question. What one would have to prove to criminally punish Trump consistent with the First Amendment is that he specifically intended to cause protesters to go beyond protest and do what they did, and that it was likely that they would do that. I think one question is the politics of the situation. Is it constructive to do that, politically? If a prosecution would be brought, would it be successful? There may be even more evidence of specific intent than we’re aware of. But I would need to know more than I do know about exactly what was said and the way in which it was said.

In September, Attorney General William Barr suggested that those who protested in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder should be charged with sedition. How was that different?

I’m not aware that the Black Lives Matter protesters were intending to, or effectively did, interfere with the functioning of government in the same way that these protesters did. I could see prosecuting them for the specific crimes—breaking windows and so on—that they committed that aren’t protected by the First Amendment. But in terms of sedition, I’m not aware that those protests were designed in any way to overthrow or interfere with government itself. As opposed to now.

I do think it’s important to invoke that concept in a way that is accurate. It’s not unusual in a time of great stress for people to exaggerate what they think. But in this situation, given what happened in the Capitol, I think using the word sedition is perfectly reasonable. The purpose of invading the Capitol while Congress was in session was clearly to directly interfere with the functioning of the government and to prevent it from operating.

In terms of civil liberties, do you have any concerns or considerations about the current moment?

It’s important to understand why the Supreme Court ultimately took such a strong free speech protective approach in Brandenburg. What it recognized, in light of our own history, is that if the government has the authority to punish people for criticizing the government, that obviously is completely incompatible with a well-functioning democracy. The Justices came to realize that the temptation to prosecute speakers for speech that is critical of the government, because they want to shut those people up, not because they actually are likely to cause any serious harm, is extremely dangerous to democracy. It has to be an extraordinarily exceptional situation to punish speech. The government can punish the actors, but it can punish the speech only in those situations where there’s really no ambiguity about what they intended and what the risks were. If you don’t have an extremely demanding standard, you invite prosecutions of critics, and that’s not acceptable.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.