Pat Mazzera/Getty

Roughly three months ago, Evanna Hu realized something had to change. For months, she and other Asian Americans working in the national security field had heard a startling number of anecdotes about a climate of fear and hostility toward people of Asian heritage. Approval for security clearances were “taking a lot longer” for some government employees and contractors. At the State Department, more Asian American diplomats are facing restrictions on where they can serve and what positions they can hold—a process that has grown so dispiriting that one employee told CNN, “It helps immensely to change one’s last name.”

For Hu, the chief executive of an artificial intelligence company that does business with the Defense Department, she began noticing microaggressions and “not-so-micro aggressions” in her interactions with government officials. “There was always this initial skepticism of my citizenship and my loyalty,” she recalled. “I finally got really fed up with it.” She turned to several peers and wrote an open letter. Signed by more than 220 people in her field, the letter condemned the “xenophobia that is spreading as U.S. policy concentrates on great power competition” and warned that it “has exacerbated suspicions, microaggressions, discrimination, and blatant accusations of disloyalty simply because of the way we look.”

Across the United States, anti-Asian hate crimes have skyrocketed in recent months. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino found that while hate crimes as a whole largely declined in the largest US cities, anti-Asian hate crimes rose by nearly 150 percent in 2020. Researchers and Asian American community leaders believe the Trump administration’s fixation on China as the source of the coronavirus—often with disparaging phrases like “China virus” or “kung flu“—contributed to an environment in which Asian Americans are more at risk. Trump’s use of the term “China virus” was “deadly for the Asian American community because it really did racialize the virus,” says San Francisco State University professor Russell Jeung, who co-founded the group Stop AAPI Hate last year. “Chinese people were stigmatized.”

When discussing China as a rival superpower vying for sway in foreign relations, Republicans were quick to use near-apocalyptic language to characterize the threat. In December, then-Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe wrote that China “poses the greatest threat to America today, and the greatest threat to democracy and freedom world-wide since World War II.” In March, Rep. Rob Wittman (R-VA), a member of the House committee that approves the Pentagon’s annual policy priorities, said “China’s goal is nothing less than the complete destruction of the United States.”

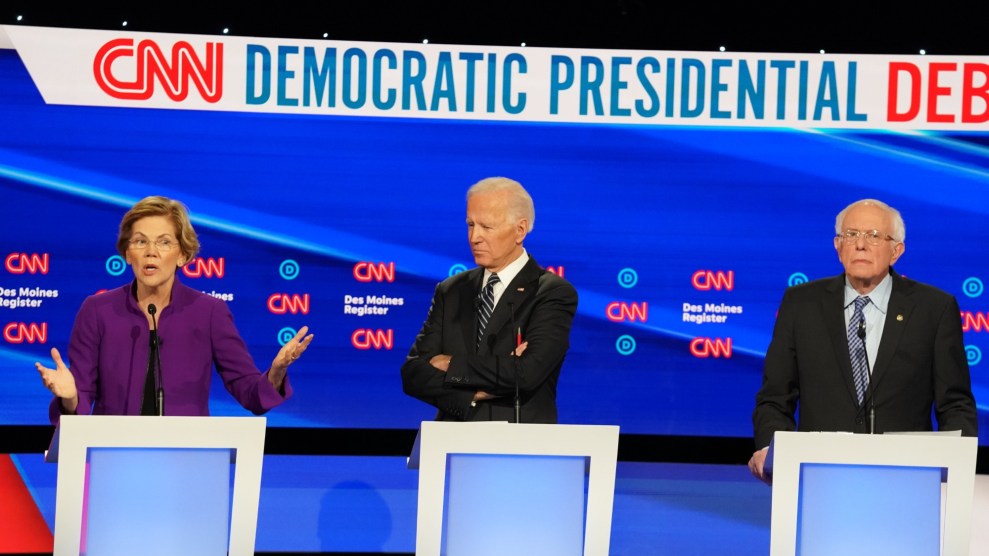

While Democrats have largely avoided the racist caricatures that Trump would employ, the emphasis on China as a top threat and rival hasn’t changed that much under Joe Biden. The president has made competition with China a key priority for the US military and described the US conflict with China as a “great inflection point in history” that determines who will “win the 21st century.” He’s even kept some of Trump’s more hawkish policies, including a wave of tariffs affecting Chinese goods, in place for now.

China’s repressive turn under leader Xi Jinping poses innumerable challenges for the region and for Chinese people themselves, who find their freedoms restricted and their cultural diversity extinguished. In the United States, China poses a much different, multilayered problem. Watch a congressional oversight hearing on nearly any topic—from espionage to climate change or trade—and China almost always comes up.

This laser-like focus on China comes with its own risks, community leaders and Asian American scholars say. As China becomes a universal bogeyman for US politicians, Chinese Americans can become targets of racism in the same way Muslim Americans were during the War on Terror. How Democrats learn to talk about China—in all its manifold complexity—may not just be key to the next decade of national security strategy. It will also go a long way toward avoiding the mistakes of the last two decades and show how serious Joe Biden is at confronting anti-Asian violence.

After the murder of eight people in Georgia two months ago, Biden went to Atlanta and said “our silence is complicity.” To Jessica Lee, a senior research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a think tank that advocates military restraint, Biden’s remarks “missed the mark in an important way.” Lee, who has written frequently about the connection between national security policy and anti-Asian violence, wrote that Biden’s White House “failed to acknowledge that Washington’s over-the-top language about China is fueling an atmosphere of fear and anxiety, which boomerangs in the form of violence against Asian Americans.”

“If there was any doubt that American foreign policy is domestic policy,” she added, “these shootings should quell them.”

Anti-Asian hate is far from a recent phenomenon in US history. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was one of the first pieces of legislation to explicitly limit immigration and remains to this day the only federal immigration restriction to single out just one specific country or ethnic group.

In 1913, California barred Asian immigrants from owning land, becoming the first of more than a dozen states to impose similar legislation. Japanese Americans, many of whom would be moved to internment camps following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, were increasingly targeted as well. Later laws that privileged the admittance of Northern Europeans at the expense of Asians and Mexicans solidified the nativist notion of the United States as a white country. President Woodrow Wilson, asked by a supporter in California for his view on Chinese exclusion, responded, “We cannot make a homogenous population out of people who do not blend with the Caucasian race.”

China and the United States—allies in World War II—found themselves on opposite sides of the Korean War and relations between the two countries were not normalized until Richard Nixon visited the country in 1972. China eventually became a global player and successive US presidents bet on its economic opening sparking a kind of social and cultural liberalization. But that bet proved wrong. The Chinese Communist Party has only become more entrenched in its rule as China’s economy has grown at a faster rate than any other modern country.

Recent hostility toward Chinese Americans corresponds with a rise in the perception of China as a predominant threat to US national security. In 2001, only 14 percent of Americans believed China was the “greatest enemy” of the United States, according to a Gallup poll. Two decades later, 45 percent of Americans listed China. The prominence of China as a national security talking point has kept Democratic lawmakers and foreign policy activists alert to the potential for the conversation to veer in a racist direction. “When this rhetoric gets out of hand and there is intense xenophobia, then there is a blowback on Asian Americans,” Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), himself a Taiwanese immigrant, said at an Asia Society event in April.

The challenge is to separate the actions of Xi Jinping’s government, which include the killing and imprisonment of Uyghur Muslims and the eradication of democratic norms in Hong Kong, from the identity of Chinese and Asian Americans. In recent weeks, progressive foreign policy advocacy groups have become especially vocal about establishing this distinction. “The relationship between the United States and China is poised to be one of the most pivotal foreign policy issues of the coming decades,” begins a memo sent out by one group, Win Without War, earlier this month. “Unfortunately, much of the current discourse on the issue—on both sides of the aisle—is steeped in a dangerous, antagonistic mindset that risks igniting a catastrophic new Cold War.” The memo goes on to emphasize the importance of cooperation with China on global issues like climate change and nuclear proliferation and rejects the notion that a threat from China “can be solved through further military buildup or economic antagonism.”

Lee, the senior research at the Quincy Institute, is one of many progressives and scholars in the antiwar community working to draw attention to examples of overheated rhetoric, especially from Democrats. Last spring, activists flagged a Biden campaign ad that criticized Trump’s sluggish response to the coronavirus pandemic. “Trump rolled over for the Chinese,” the ad’s narrator says at one point.

Asian American activists were not pleased, as Politico reported at the time. “Wow @JoeBiden. Already trying to out-Trump Trump,” Cecillia Wang, a deputy legal director at the national ACLU tweeted. “This kind of fearmongering is causing violent attacks on Asian Americans.” When Biden released a follow-up ad weeks later, the tone softened considerably. There was no mention of “the Chinese” or of Trump’s travel ban, which the first ad had maligned as “not exactly airtight.”

Since taking office, Biden has kept the national security focus on China as congressional Democrats work to pass a bipartisan package of bills aimed at preserving the US supply chain—given China’s control of exports crucial to the production of electronics and certain medicines—and countering Chinese influence domestically. This latter bill, known as the Strategic Competition Act, spawned a series of condemnatory articles from Quincy scholars, who said it “would effectively constitute a declaration of cold war on China by the U.S. Congress.” The legislation, pushed by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), treats Chinese “influence” as a global terror and includes a $300 million fund “to counter the malign influence of the Chinese Communist Party globally.”

Even Biden’s defense budget uses China as an implicit argument for more funding. When his administration announced its request for $715 billion in defense spending in April—a rejection of progressive demands to cut the budget from last year—a White House statement said the budget considers “the need to counter the threat from China” as the Pentagon’s “top challenge.”

For Democrats, the relentless focus on competing with China on trade and manufacturing not only creates some common ground with Republicans, but also could interest workers eager for an aggressive attempt to keep jobs in the United States. It also invites other problems—which progressives are quick to point out. Erica Fein, senior Washington director at Win Without War, says “it’s a big problem that Democrats believe they can score cheap political points by being hawkish towards China.”

“Not only does it lead to more xenophobia and racism at home, it could even lead to an actual war,” she adds. “This is one of the biggest challenges for the progressive movement, and it’s going to take a major shift in priorities to get us where we need to be.”