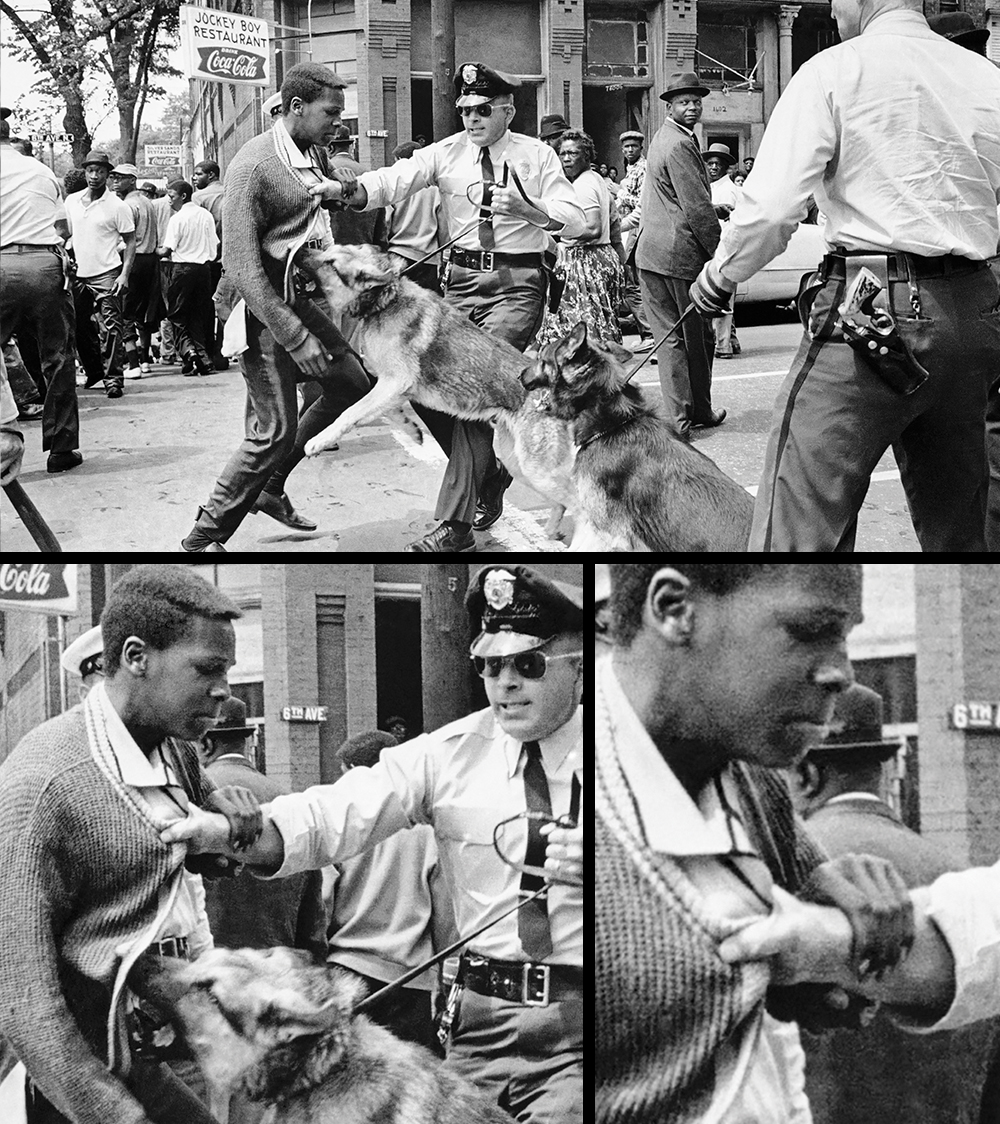

In 1963, Walter Gadsden, 15 years old, was attacked by a police dog during a protest on the streets of Birmingham, Alabama. The moment was captured by Bill Hudson of the Associated Press. His photograph was later said to have brought the world to the side of the civil rights movement—a grand claim but not an unreasonable one, given both the photo’s mass circulation and the meanings ascribed to it by white audiences.

Gadsden was a “frail Negro,” in one description; full of “saintly calm,” in the words of Diane McWhorter, paraphrasing the photographer’s editor. The writer Paul Hemphill, in his memoir of growing up in Birmingham, saw a “thin well-dressed boy seeming to be leaning into the dog, his arms limp at his side, calmly staring straight ahead as though to say, ‘Take me, here I am.’” Hudson’s photo offered a drama of wholesome nonresistance, with Gadsden in the role of a martyred innocent.

But something was obscured in that narrative, as Martin Berger argues in Seeing Through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography. The white gaze skipped right over the signs of Gadsden’s resistance—the hand on the cop’s arm, the left knee thrust into the dog’s chest. These details did not fit with the prevailing picture of the struggle for civil rights. What white people saw instead was Black passivity. In Gadsden they saw a vulnerable boy who, like Black people throughout the South, was in need of white help. The photo may have drawn sympathetic white liberals to the cause of racial justice, but it did so, Berger writes, on terms that allowed them to feel secure and magnanimous, as if they were “bestowing rights” on Black people.

In May 2020, people again took to the streets, this time in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder. Many things had changed since the day Hudson trained his lens on Gadsden. The Black Lives Matter movement enjoyed broader support than the civil rights movement did in its time, and the media documenting the uprising was no longer so monochromatically white.

But were things really all that different? I looked at front pages of the New York Times and the Washington Post during the hectic early days of the protests and saw several familiar tropes, marshaled in familiar ways. The visual portrayal of the uprising was operating within the same boundaries established by well-meaning but ultimately self-interested white liberals during the civil rights era. Now as then, it seemed, the principal concern was to channel and validate white response to Black rebellion in the streets.

A Black person at the mercy of a white person or the state was a familiar image during the civil rights movement. Think of the photos of lunch counter sit-ins where white people screamed Black people down, or the photos of water hoses turned on kids during the Children’s Crusade in 1963. Today, “passive” Black people may have their hands in the air, or perhaps they are being carted away by police in riot gear. For white audiences, these photos stamp innocence onto Black people, thus translating the protest into an acceptable cause.

In this image from the May 30 Washington Post, a Black man kneels with his fists raised. Black viewers have tended to read photographs like this one as “images of power,” Berger tells me in an email. “After all, it takes strength to calmly confront militarized police to make one’s principled point.” On the front page of an establishment newspaper, however, different meanings more readily assert themselves. The man’s hands in the air represent the compliance demanded by the state, as embodied by the indistinct armed figures in the distance. The primary colors lock in the gaze, and the longer you linger, the more you might feel as if he is offering up his body, just as Walter Gadsden seemed to. The viewer is invited to appreciate the man’s ironclad will, his brave forbearance; the viewer is not implored to consider the desperation and anger it might have taken to put himself in that position in the first place.

Front page photo: Carlos Barria/Reuters

Photos from the urban uprisings of the late 1960s presented a different image of Black protest. Black people were now “forceful figures,” Berger says. They were no longer protesters; they were rioters. Media coverage tended to focus on the aftermath of riots, reinforcing white discomfort and solidifying resistance to anything other than a “peaceful” protest.

The person depicted here could be of any race; all the viewer registers is the dark figure—“literally black,” says Michael Shaw, publisher of Reading the Pictures, a website dedicated to analyzing the visual framing of social issues—silhouetted against a backdrop of destruction. “You can see that this generation and so much of the images that come out of this are forceful, are pushing back upon that authority, where the images beforehand were pulling for that sympathy,” says Brent Lewis, a Black photo editor at the New York Times and the co-founder of Diversify Photo, a site promoting the work of nonwhite photographers. Shaw was put in mind of “war photography,” calling it “a very toxic photograph, very loaded.”

The accompanying headline, “spreading unrest leaves a nation on edge,” only furthers the sense of anxiety. Of course not everyone was on edge in that moment—what of the people who felt a sense of joy and liberation watching Minneapolis’ Third Precinct burn down?—but the assumptions embedded in the presentation give a sense of the upper bound of the liberal establishment’s sympathy with the cause. Yet, while the riot photos may have evoked the imagery of the late 1960s, Berger points out that they were not received in the same way: “Millions of whites in the 21st century were able to look at these images of powerful Black actors without losing their sympathy or pulling back” from the cause.

Front page photo: Victor J. Blue/New York Times/Redux

Large, diverse crowds were irresistible subjects of last year’s protest coverage. “There’s a kind of anonymity to them and a redundancy,” Shaw says. The protesters are always squeezed into the frame, suggesting a crowd bursting at the edges, and signage is usually prominently featured. The mildness of these images reassures white viewers that the protests are peaceful while also communicating the scale of both the problem and the resistance to it. Berger notes the Black marchers holding up cell phones in the crowd shots—“individuals who have taken charge of their self-representation…no longer reliant on the white press to get their stories out.”

In this package from the June 16, 2020, Washington Post, Shaw sees “an interesting juxtaposition where you get a dialogue between the photographs.” The allusions to the civil rights era in the crowd shot—the “I AM A MAN” sign, with “KING” in the distance—are paired with the intimate portrait of Rayshard Brooks’ family, as if history itself were beckoning the viewer to come to the rescue of Black humanity.

Front page photo: Dustin Chambers/Getty

These photos are from different protests, yet they were placed together on the New York Times’ June 1 front page. Good vs. evil is the narrative. Note the ominous, depersonalized image of the police, portrayed like an alien invasion against the unarmed, white-presenting demonstrators in the streets of Brooklyn. As with the images from the 1960s, it’s clear who the bad guys are supposed to be. White viewers are thus reassured that they are not complicit.

The conflict, in the package’s telling, is about the cops and the violence they inflict on Black people—true enough but only part of the story. “Many millions of liberal whites have no problem seeing the problem of race as one of violent police,” Berger says. “That allows them to distance themselves from racism, since they can’t imagine themselves perpetrating white-on-Black violence. White outrage at police conduct downplays their complicity in a racialized system that benefits whites.” Until white people examine how they can be participants in a movement against police brutality and still receive racism’s dividends, America will keep spinning in circles. In the early days of the uprising, the action in the streets challenged the white response. The front pages of the country’s establishment newspapers seemed to coddle it.

Front page photo: Victor J. Blue/New York Times/Redux