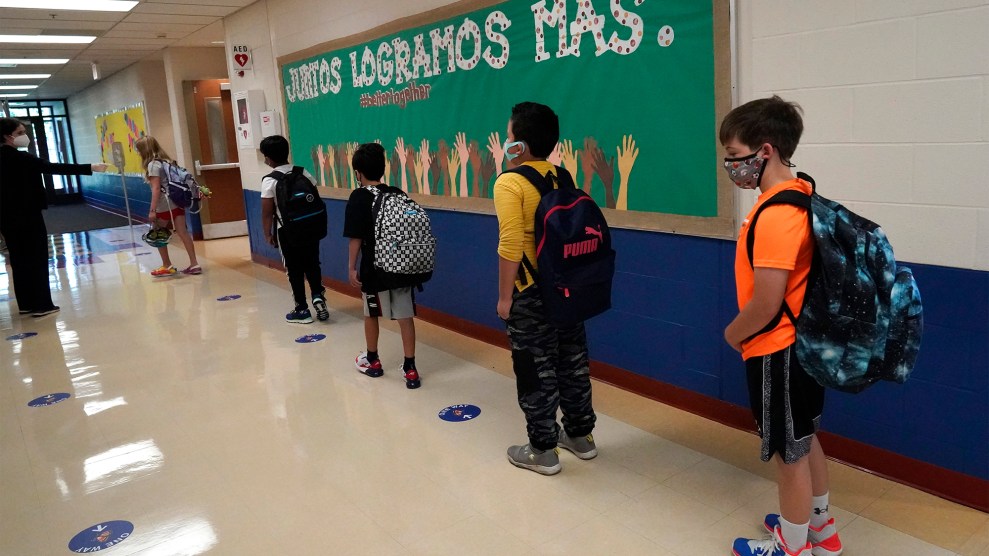

Students keep social distance as they walk to their classroom in Highwood, Illinois, in 2020.Nam Y. Huh/AP

This weekend, teachers in more than 30 cities protested against new laws that would limit what they can say in the classroom about racism in the United States.

The laws—in Texas, Idaho, Arkansas, Iowa, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Arizona, North Carolina, and other states—have emerged since George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota, after more teachers expanded lessons about systemic racism. Many of the laws ban schools from exploring “critical race theory,” which holds that any study of American history must acknowledge that racism is deeply embedded in government policies and the legal system. Some of the laws are even more broad, seeking to restrict lessons that focus on marginalized groups or equity. There’s money behind them, too. A new political action committee, the 1776 Project PAC, is fundraising to support school board members and others who push similar bills.

The conservatives cheering these new restrictions likely took a recent cue from former President Donald Trump—who during his term accused schools that teach kids about slavery of spreading “hateful lies” and insulting the country’s founders. Trump created the 1776 Commission to promote a “patriotic education,” as his administration called it, and to glorify America’s founding in ways that many historians deemed inaccurate and misleading. It’s just the latest in a long, long history of Republicans fixating on the education system as a way to push reactionary conservatism—from abstinence-only education to the Pledge of Allegiance. They accuse teachers who try talking frankly about race of being overly political and divisive with kids—as if the way we currently teach about racism in America, often by glossing over the subject, isn’t already extremely political.

On Saturday, thousands of teachers across the United States went online or hit the streets to show their frustration. In Memphis, according to the Washington Post, protesters convened at the location where Ku Klux Klan grand wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest once ran a market of enslaved people during the mid-1800s.

#TeachTruth at @TheStonewallNYC National Monument NYU professors and NY teachers. pic.twitter.com/WOB6e9NNuI

— Zinn Ed Project (@ZinnEdProject) June 12, 2021

Today was a beautiful outpouring of support to #TeachTruth in Portsmouth, NH ❤️⭐️🎼 pic.twitter.com/4OXMhv7NmS

— Misty LC (@Misty_Crompton) June 12, 2021

12 year old Jordan: "Most of my teachers told me how to count. But they didn't teach me what counts." #TeachTruth pic.twitter.com/4PMgf1rBvo

— Mike Tanier (@MikeTanier) June 12, 2021

Belton, TX pic.twitter.com/wOsQfjWNV0

— Richard Beaulé (Rick) (He/Him) (@loudguyrickyb) June 12, 2021

The national day of action was organized by the national coalition Black Lives Matter at School, and by the Zinn Education Project, a nonprofit that offers learning materials based on Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, a well-known book that focuses on the role of workers, women, and people of color in American history. Several thousand teachers signed a pledge that they would not follow the new Republican mandates. “We, the undersigned educators, refuse to lie to young people about U.S. history and current events—regardless of the law,” they wrote.

Earlier this week, my colleague Edwin Rios summed up why these laws are so worrisome:

One of the problems, and there are many, with this latest Republican obsession to frame anti-racism teaching as a bogeyman is that it seeks to impose broad, vague prohibitions on how racism is taught in America’s schools and cites a specific line of academic inquiry as a proxy for preventing schools from teaching a more raw, less whitewashed framing of American history. And conservatives have leveraged outrage over such teaching to enflame a culture war on schoolhouse grounds as a way to denigrate any conversations about race and equity—an effort that could have long-term ramifications not just for students in classrooms but the American public.

Some teachers worry that the new legislation is already having a chilling effect on educators who just want their students to think more about privilege and racial oppression. “I will say it’s already playing out,” sixth-grade teacher Monique Cottman was quoted in the Post as saying. “The white teachers who started doing a little bit more teaching about race and racism are now going back to their old way of teaching. I’ve had conversations with teachers who said things like, ‘I’m getting so much pushback for teaching Alice Walker, I’m going to go back to teaching what I used to teach.’”