President Joe Biden speaks about the bipartisan infrastructure bill from the East Room of the White House in Washington on August 10, 2021.Susan Walsh/AP

When Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.) said last month that she couldn’t support a $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) didn’t mince her criticism. “Good luck tanking your own party’s investment in childcare, climate action, and infrastructure,” Ocasio-Cortez tweeted in response. The New York lawmaker warned such a move wasn’t likely to “survive a 3 vote House margin,” dangling the ever-looming threat that her fellow House progressives could take down both a budget bill they deemed insufficient and the bipartisan infrastructure deal Sinema had just helped to negotiate.

At first blush, the chiding seemed to simply follow the well-worn grooves of Democrats’ intraparty fights. Ocasio-Cortez, a vanguard of the House’s left flank, chastised a moderate Arizona senator for her unwillingness to put federal resources behind the social programs that progressives favor. But the overwhelming majority of what’s in the $3.5 trillion budget bill isn’t just a progressive wishlist: It’s the bulk of President Joe Biden’s agenda, much of which ended up on the cutting room floor of the bipartisan infrastructure deal the Senate passed on Tuesday. The reconciliation bill—which includes major investments in child care, climate initiatives, housing, and education—isn’t subject to the Senate’s typical 60-vote threshold and can pass the chamber with a simple majority of Democratic votes.

Once it became clear in January that Democrats were going to have the tie-breaking vote in an evenly split Senate, this year’s congressional session was set to become a debate between an empowered progressive wing in the House—led most notably by Ocasio-Cortez and other members of the Squad—and a more moderate faction of Democratic senators. The president, as the party’s head, would assume the role of peace broker. And Biden, who vanquished his progressive 2020 rivals with a moderate platform and a penchant for bipartisan dealmaking, seemed most likely to side with the Sinemas than the Ocasio-Cortezs.

But as Congress considers an infrastructure proposal and reconciliation deal likely to define Biden’s legacy, it’s the moderate lawmakers, not the left flank, who are most willing to publicly rebuke the main ideas Biden has presented as his agenda. And Biden, so far, has leaned in favor of the progressive’s playbook when it comes to getting that agenda over the finish line.

The Senate’s moderating forces on Biden’s ambitions over the first half-year of his presidency are well-documented. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) exercised so much influence over the White House’s COVID relief package that his colleagues referred to him as “your highness.” He ground progress on Democrats’ COVID relief package to halt at the eleventh hour to bend the bill’s unemployment enhancements to his liking. Manchin shares Sinema’s skepticism over the $3.5 trillion in spending, though he promised to vote for it “out of respect for my colleagues.” Both moderates did, in fact, vote in favor of opening debate on the overall spending number after passing the infrastructure bill on Tuesday. But Manchin said he’s “very, very disturbed” by the budget’s line items intended to reverse the effects of climate change—line items he’ll have ample control over as the chair of the Senate’s Energy and Natural Resources committee.

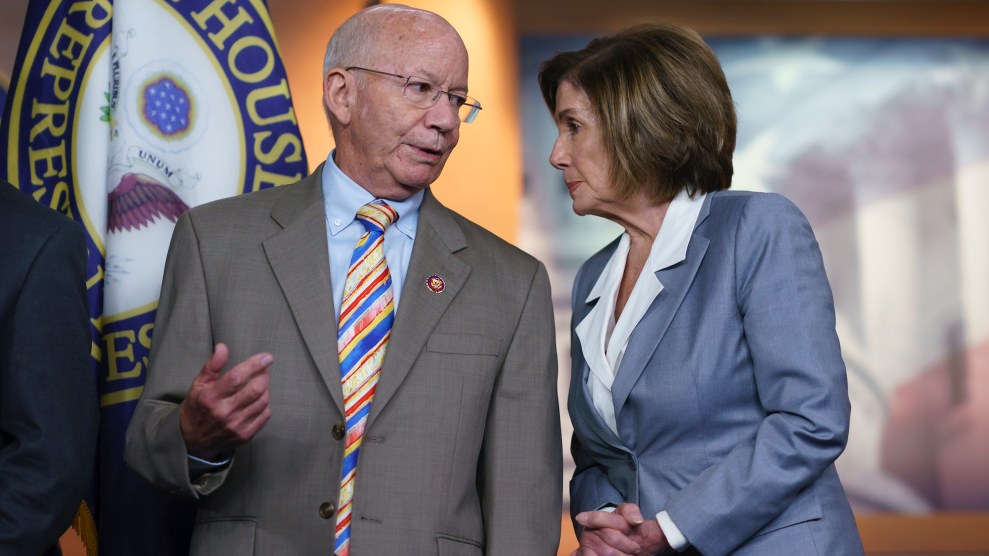

While Manchin and Sinema are likely to support some eventual party-line bill, the same can’t necessarily be said of their centrist House counterparts. Two of them have already vowed to vote against any reconciliation bill, regardless of size. Last weekend, six moderate House Democrats began circulating a letter demanding that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) hold a vote on the bipartisan infrastructure bill that passed the Senate on Tuesday “as soon as the Senate completes its work.” That request contradicts Pelosi’s promise to bring up the infrastructure and the reconciliation bills for votes at the same time, a maneuver designed to ensure the overall package of Biden’s agenda gets over the finish line.

The looming reconciliation fight is just one in a string of recent instances in which moderate Democrats have bucked the White House. After the Supreme Court ruled in June that it would be up to Congress to extend the federal eviction moratorium past its July 31 expiration, centrist House Democrats conveyed to Pelosi that they weren’t interested in passing an extension. That forced the White House into a politically dicey position of navigating what executive action might be allowed without invoking the wrath of Brett Kavanaugh. It also denied Democrats a clean political win of being able to squarely blame Republicans for blocking relief.

For most of the 2020 presidential campaign and transition, the Democrats’ progressive wing had been portrayed as the president’s chief intra-party antagonizers. The left pointed to Biden’s track record on criminal justice and bankruptcy reform as evidence of his unwoke, corporatist past. Biden rode through the presidential primary in the centrist lane, touting promises to reach across the aisle. Progressives spent the transition preparing to squeeze the incoming administration, recalling how President Obama had iced them out. Instead, they encountered a White House responsive to their priorities, which have been reflected to a large extent in the pair of economic proposals intended as cornerstones of Biden’s legacy.

This isn’t to say that progressives haven’t been a thorn in the White House’s side. Left-wing lawmakers and their allies have relentlessly pushed Biden to throw his weight behind ending the filibuster and urged him to fight more vigorously for legislation blocked by the rules, such as Democrats’ voting right agenda. They, too, are agitating for a fight on the infrastructure deal: Rep. Pramila Jayapal, chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, echoed Ocasio-Cortez’s warnings on a call with reporters last week, promising “any number of members in the House” are also willing to “vote ‘no’ if certain things don’t happen. But for the most part, those “certain things” are holding their colleagues to a watered-down version Biden’s more aggressive agenda as the baseline, and pushing for more spending on programs if they can.

The White House hasn’t criticized agitators from any wing of its party as its attempts to shepherd the bills through the House and Senate. The slim margins offer a practical incentive for keeping mum: The reconciliation bill needs the support of every single Democratic senator and all but three Democratic House members in order to become law. There’s also a good chance the intra-party tensions resolve themselves. Democrats desire to appear both unified and capable of delivering measurable results ahead of the 2022 midterms, a strong incentive to skip red lines in favor of compromise.

Biden’s official Twitter account heralded the passage of the bipartisan Senate bill with a call to Congress to send it to his desk “as soon as possible,” language that seemed to echo moderates’ preferences. But White House press secretary Jen Psaki clarified later Tuesday that the president will work “in lockstep” with Pelosi on the sequencing of the bills, deference that preserves his agenda and progressives’ desires. On matters of style, Biden sees himself in the moderates, preferring across-the-aisle dealmaking to partisan warfare. But he’s unwilling to put that style ahead of substance in pursuit of his legacy—a legacy that, for now, is more closely aligned with his party’s left flank.