Martin Barraud/Getty Images

Cook County Associate Judge Stuart Katz wanted to try something completely different. The Illinois juvenile court judge was sick of the usual options: locking up young people or sentencing them to community service. More “creative” approaches, like mentoring or drug treatment programs, helped the kids who had been prosecuted, but they did little for the people those kids hurt, Katz says. “You also want to give back to the community,” he explains, “and back to the victim.”

So in 2011, he launched a program to give convicted youth the option to participate in a restorative justice process, in which people who cause harm, and those affected by their actions, are brought together for a facilitated dialogue. Together, they reach an agreement about how to repair whatever damage has been done. For a hungry child who stole a bag of Cheetos from a Target, such an agreement might involve a community nonprofit helping his family get food stamps, says Patrick Keenan-Devlin, executive director of the Moran Center for Youth Advocacy, an Illinois juvenile defense and social work nonprofit. In a hypothetical case of sexual assault, it might involve a perpetrator fully admitting their guilt to a survivor. Kids who successfully participated in the process set up by Katz, which was facilitated by a local Catholic restorative justice group, received community service credit that counted toward their sentence.

For the first 10 or so kids who opted in, the program was “hugely effective and transformative,” says Katz, who is now retired. One marker of its success was the recidivism of participants, which fell to almost zero. According to Katz, one child who was caught breaking into a police officer’s house ended up playing on a basketball team coached by the cop after they went through the process. “It was just amazing, and the sort of thing that absolutely never would have happened had it not been for that kind of a program,” Katz says. “That was so clearly the intent of the restorative justice program—to help these kids not recidivate, to help them understand, to let them get what help they needed, and to deal with this on a more personal level, and not just as a cold courtroom.”

But it wouldn’t last. Before long, public defenders started declining Katz’s offers for restorative justice, worried that whatever their young clients admitted during the process might later be used against them in court. “Just like any other criminal defense lawyer, they’re not going to allow their client to incriminate themselves,” says Amy Campanelli, the former chief public defender in Cook County. Restorative justice, Campanelli explains, involves an open discussion about why a person did what they did, to get to the root causes of a harmful behavior. But if, for example, a participant arrested for selling heroin to an undercover cop says they dealt drugs for years to support an addiction, what’s to stop a prosecutor from tacking on additional possession and trafficking charges? Even when restorative justice practitioners use their own confidentiality agreements, “people can drive Mack trucks through loopholes within those,” Keenan-Devlin says.

Without a guarantee that statements made in restorative justice wouldn’t be used against the kids who opted in, Katz’s program fell apart in 2012. Now, a new law might make programs like Katz’s possible again. In July, Illinois lawmakers attempted to solve the problem that plagued it by barring any statements made in a restorative justice process from being used later in lawsuits, prosecutions, or other court proceedings. The “privilege” now granted to restorative justice in Illinois resembles the same protections afforded to conversations between doctors and patients; therapists and clients; or in legal mediation. It doesn’t prohibit participants in restorative justice from disclosing what’s said in the process. But it prevents those disclosures from being used later to prove a legal case. “It really is about evidence—what can come into a court of law from those sanctioned relationships,” says Keenan-Devlin, the law’s co-author.

With its new law, Illinois joins a small group of states—including Delaware, Nebraska, and Tennessee—that have created special protections for what’s said in a restorative justice process, according to a database maintained by Shannon Sliva, a professor of social work at the University of Denver. But Illinois’ may be the broadest, because it recognizes not only “victim-offender dialogues” used in the criminal legal system, but also grassroots processes that aren’t directly associated with the courts, such as peace circles run by schools, nonprofits, or individual practitioners. Sliva, who has tracked over 240 pieces of restorative justice legislation passed from the 1970s to 2019, says the law’s definition of restorative justice is unusual because it uses the language of restorative justice practitioners rather than that of the criminal legal system: It references “parties who have caused harm” rather than “offender,” as well as trauma and a goal of strengthening community ties.

While state laws authorizing and governing restorative justice have become increasingly common, Sliva says, they don’t always yield an uptick in the use of restorative processes. Proponents of the new Illinois law believe it is essential groundwork for the spread of such practices. “That’s the big question,” Sliva says. “If, a year from now or three years from now, or five years from now, that Illinois finds that the passage of this bill has expanded access.”

Supporters see restorative practices as a powerful alternative to the traditional justice system, in which judges and prosecutors representing the government send people to prison as a way of punishing past crime and deterring future crime, with “rehabilitation” an afterthought if it happens at all. Victims, meanwhile, have their testimony used by a prosecutor to secure a conviction, but are otherwise left out of the justice process. Supporters argue that restorative justice, in contrast, allows victims to define what “accountability” and “justice” mean to them; the people who cause harm get an opportunity to right their wrongs to the extent possible while being supported by their community. Ideally, this prevents them from committing the same crime again. “Restorative justice is a way to create or reestablish relationships where they’ve been broken. It puts names and faces to these things in a way that we haven’t done in quite some time,” says Tanya Woods, whose Chicago-based organization, the Westside Justice Center, uses restorative practices to resolve matters that otherwise would go to civil court. But participants have to feel safe enough to be honest—and in most places in the US, restorative justice conversations are not privileged. “If people are guarded by what they think they can say, you don’t have an honest, open and candid process or conversation, because people have to be worried about what they’re going to say being used against them later,” Woods says. “It almost damns the conversation before it even gets started.”

“We really want to see restorative practices practiced universally,” Keenan-Devlin says. “We wanted the state, essentially, to condone restorative practices, and communicate out to the residents of the state of Illinois that this is something we encourage. So when you communicate in a restorative setting, you know that the tentacles of the state will not be present, and will not undermine—I’m going to talk like a Catholic for a second—the sanctity of that practice.”

Restorative justice isn’t a religious concept, but Illinois’ new restorative justice privilege law originated in Chicago’s Catholic community. In 2015, during a series of meetings on restorative justice held by the Catholic Lawyers Guild of Chicago, Katz aired his frustrations with the failure of his old program. Other attendees, including Keenan-Devlin, proposed drafting a rule change for the Illinois Supreme Court that would create a restorative justice privilege. When that effort failed, a coalition of advocacy groups led by the Evanston-based Juvenile Justice Initiative brought the idea to the legislature.

Restorative justice had already gained a little ground in the state. At the urging of the legislature, the Juvenile Justice Initiative had begun researching restorative justice in 2015. Focusing on Northern Ireland, which implemented restorative justice for youth after the Troubles, and other places abroad, they found that other countries broadly followed the United Nation’s principles for the use of restorative justice programs. “One of these critical principles is confidentiality,” says Betsy Clarke, founder and president of the Juvenile Justice Initiative. “You can’t have a restorative justice practice without people feeling safe.” Over the following year, Clarke’s group worked with a London-based foundation to help the Circuit Court of Cook County create “restorative justice community courts.” Launched in 2017, those courts now operate in three neighborhoods, handling nonviolent cases involving young adults. Meanwhile, schools in Chicago adopted restorative processes to deal with student discipline problems without suspensions or other punishments.

But it took three attempts for the privilege legislation to pass, after bills died without a floor vote in both 2019 and 2020. This year, SB 64 sailed through the Democratic-majority legislature—passing the state Senate mostly along party lines, and winning over a handful of Republicans in the state House of Representatives.

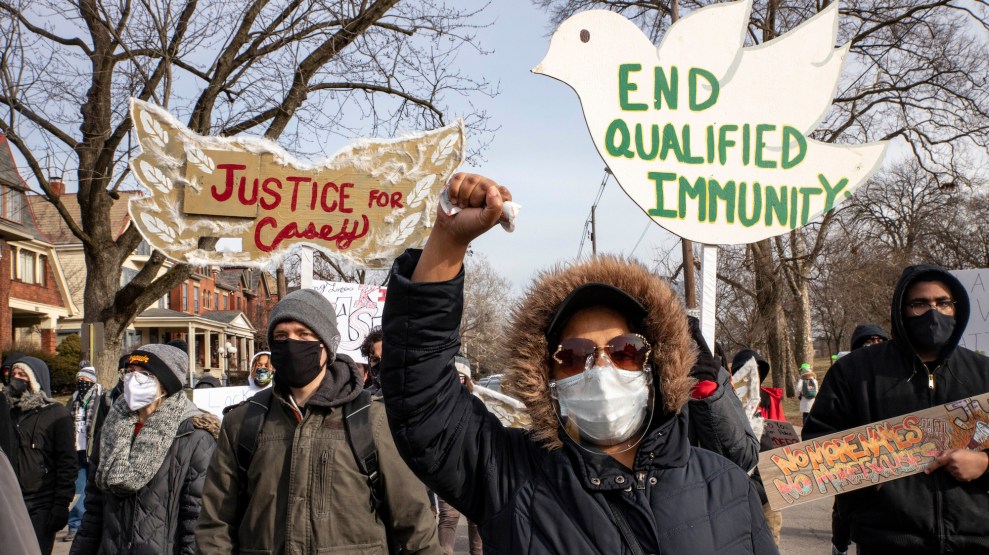

What changed? “The death of George Floyd,” Katz says simply. In response to last year’s uprising against racism and police brutality, the Illinois legislature made major changes to the state’s criminal legal system, passing landmark bills to abolish cash bail, expand prisoners’ rights, and create a new process to decertify abusive police officers. “Floyd’s death made people aware that we need to do things differently,” Katz says. “Restorative justice was one of the things that started getting thrown out there as an alternative to police, when you talk about defunding police in a broad sense.”

Black and Brown communities have the most to gain from restorative justice, Woods argues, because they’re the ones most hurt by the punitiveness of the traditional justice system. “The cumulative effect of unfair and unjust systems weighs more heavily upon those who’ve already been oppressed for generations,” she says. “It hurts us more than it hurts anybody else. Because we’re more likely to be picked up off the street, arrested, for crimes that if we lived in Glenview, probably somebody would just call our parents.”

But in addition—and crucially, according to Clarke—victims’ rights organizations also lined up to support SB 64. Advocates for survivors of gender-based violence argued to the legislature that restorative justice isn’t simply a way for perpetrators to avoid jail time—it gives survivors a much-needed option for pursuing accountability, justice, and healing.

“We have survivors who are walking in the door and saying, ‘This person harmed me. I don’t necessarily want them to go to jail. I don’t want them to go to prison,’” says Madeleine Behr, policy manager for the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation. Some of those survivors don’t want to go through the often retraumatizing process of reporting to Chicago police, who have a poor track record of responding to reports of sexual harm—making arrests in only 10 to 20 percent of cases, according to a CAASE analysis. Others are looking for alternative forms of redress, or simply for their abusers to take responsibility for hurting them. For those survivors, Behr says, restorative justice ought to be an option. “Part of restorative justice is making sure that the survivor can really hear from the person that harmed them that they admit to what they did,” Behr says. “The survivor can specify what they need from that person to be able to heal. It can be really tailored to what the survivor wants.”

“But that can’t happen,” she adds, “if the people who have caused harm can’t really fully open themselves up to that process.” Before SB 64 passed, when survivors asked CAASE about restorative justice, advocates had to let them down gently.

Having gender-based violence survivors on their side “completely changed the politics,” Clarke says. “That really countered any concerns by law enforcement. Once you have groups that have been harmed, survivor groups, coming forward and saying, ‘We need this option,’ then prosecutors, sheriffs—whatever they say doesn’t carry as much weight.”

“There is often this perception that criminal justice reform and supporting victims are counterintuitive and oppositional,” Behr says. “We fundamentally repudiate that every chance we get. We can create systems that are beneficial to all parties, and make communities safer, and actually create the kind of accountability and justice that people are looking for.”

Of course, there are far more barriers to expanding the use of restorative justice than just the issue of privilege. Sliva, at the University of Denver, points to persistent reluctance among judges and prosecutors to use restorative justice, even when their state has passed legislation authorizing it. Campanelli, who became vice president of restorative justice at Lawndale Christian Legal Center after the end of her term as Cook County public defender, argues that another barrier is money—politicians who don’t believe that restorative justice can effectively address crime pour money into law enforcement and prosecution, rather than community-oriented solutions.

Restorative justice, after all, is also a challenge to those who currently hold power in the criminal justice system. “It’s taking the power away from the judge and the prosecutor,” Campanelli explains. “It’s the community who’s going to have a say in this, and say, ‘Look, we know we know what the effects of crime are on our community, and we’re going to change it. And here’s how we’re going to do it.'”