J. Scott Applewhite/AP

As a showdown unfolds on Capitol Hill this week over multiple pieces of key legislation—including a funding bill necessary to avoid a government shutdown beginning on Friday—major banks have zeroed in on one wonky and critical piece of the fracas in Washington: the debt ceiling.

This rule limits how much money the US government can borrow to pay for its existing obligations, from Social Security payment to tax refunds. And as the October 1 deadline to fund the government has inched ever closer, it has brought out some forceful language from the traditionally staid realm of banking and finance.

Earlier this month, a Goldman Sachs report called this “the riskiest debt limit deadline in a decade.” The chief economist of Moody’s Analytics told CNN that if the ceiling weren’t raised, it would usher in “financial Armageddon,” while JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon warned that it would cause a “cascading catastrophe of unbelievable proportions and damage America for 100 years.” This week, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen advised lawmakers that without action on the debt ceiling, the US will run out of money on October 18—at which point “our country would likely face a financial crisis and economic recession.”

Lawmakers are expected to vote Thursday on a short-term bill that would fund the government into December. But in order to cull enough GOP votes, the bill does not include a debt cap increase. This will leave Congress with just a few weeks to solve that problem. The Washington Post reported Thursday that the Treasury department asked federal agencies to review their spending plans for the month of October—signaling even more concern that the US government is at a real risk of running out of cash for the first time in history.

This is what it looks like when the financial system is really worried. Certainly banks and government officials have expressed their concerns before—the Federal Reserve even penned a secret, complicated crisis plan for a potential default that the Wall Street Journal revealed this week. And while the debt ceiling has always had major implications for the economy, the reaction of banks, financial analysts, and Treasury officials, this go-round has been especially severe because of a dangerous mix of economics and politics: the dire financial system consequences that would accompany inaction, and the extreme Republican obstructionism that has come to surround this particular fight.

“If you’re a bank looking at this, you don’t really need to know anything about the debt ceiling to see how the politics have just radically changed,” says Neil Buchanan, an economist and law professor at University of Florida’s law school, and the author of The Debt Ceiling Disasters. “This time, the Republicans seem willing to actually burn down the house.”

To fully absorb the scale of this moment, it’s helpful to review a brief (I promise!) history of debt ceiling fights in Congress. The debt limit has been raised or suspended 78 times since its creation more than a century ago, when Congress created the debt ceiling (and the concept of raising it) in order to afford the government more flexibility to borrow money during World War I. It has stuck ever since, leading to numerous political fights over funding many things, from the national highway system to the Vietnam War and social safety net programs, even though the concept doesn’t exist in most other countries. (It should also be noted that raising the debt ceiling does not create extra spending—it is a way of funding the items that the US government has already committed to.) No group of lawmakers has ever opted not to raise the debt cap, despite several close calls during the Obama era, when House Republicans withheld votes on the debt cap to try to force cuts to federal spending. But regardless of political differences or party control, Congress has always been able to agree that the consequences of not raising this limit are just too severe.

If Congress doesn’t raise the debt ceiling, the US will default—econ-speak that means the US government won’t be able to keep paying back its debts, particularly Treasury bonds. These are the bedrock of the global financial system, considered to be the safest of assets for the express reason that the US has never, in the history of time, defaulted on its debts. Default would likely have numerous ripple effects. The stock market would crater, leading to a loss of up to $15 trillion in Americans’ wealth, according to a Moody’s analysis. Mortgage rates and interest rates on other types of consumer loans would surge. And up to 6 million jobs would be lost, sending the unemployment rate up to about 9 percent, per Moody’s estimates.

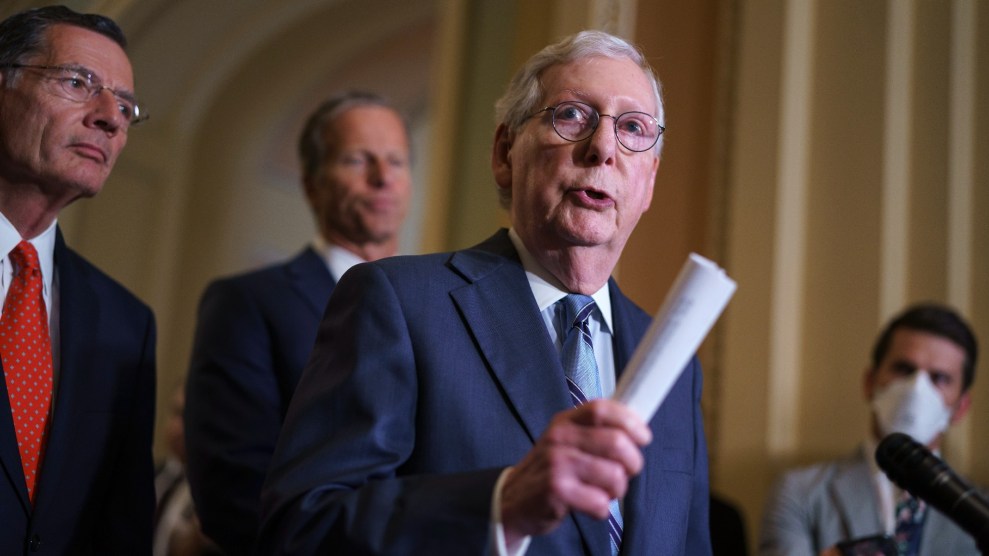

But now the US financial system is once again barreling toward this unprecedented result, thanks to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and the GOP. They have vowed to obstruct efforts to raise the debt limit and are using it as an extreme bargaining chip in their effort to block Democrats’ other priorities. Despite having raised the debt ceiling with Democratic cooperation multiple times during the Trump administration—including during COVID, to accommodate infusions of cash needed to cushion the pandemic economy—Republicans now say that Democrats, who hold slim majorities in both chambers of Congress, should raise the debt ceiling without GOP help. On Tuesday, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer sought unanimous consent to do just that—asking to bypass the typical 60-vote threshold to allow Democrats to raise the limit with a simple 51-vote majority in the Senate. McConnell blocked the measure. The New York Times deemed it “political sabotage.”

There are two other elements that make this particular debt ceiling fight especially concerning to banks and financial analysts, says Linda Hooks, an economics professor at Washington and Lee University in Virginia. The first is that this battle is linked to Democrats “historically large” $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation bill—and with that comes political unpredictability. The other, she notes, is the COVID economic recovery, which is still quite fragile.

Exactly a decade ago, Republicans also held the debt ceiling hostage to force other concessions from the Obama administration. That moment—like this one, Hooks notes—was on the heels of a historic economic crisis: the Great Recession of 2008. But this moment is even more precarious.

“By 2011 we had a sense of a recovery in progress,” Hooks says. “Right now we are less sure of that. We’re in a recovery, but a fragile recovery. The economic outlook is cloudier.”