It’s been a long time since I sat in an American history class, but what I remember of my education in Jacksonville, Florida, in the 1980s and ’90s is how much of it was not fact, but myth.

I was taught that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights—a concept that seemed plausibly defensible to a kid—and that “our side” had its own heroes and its own stories worth remembering. Several of my relatives who live in north Florida still fly the Confederate flag on their boats and paste Stars and Bars stickers on their trucks. Some of them wear it on T-shirts, claiming, of course, “heritage not hate.” But to me, what the Confederate flag celebrates is Southerners’ long tradition of lying to ourselves about the past.

Some of the most obvious, in-your-face lies are in the huge physical reminders—the monuments, markers, and signs venerating the Confederate dead. Most of these monuments didn’t go up immediately following the Civil War. They first appeared in the 1890s as part of the backlash to Reconstruction. A second wave took place in the 1950s and ’60s during the civil rights movement. These weren’t coincidences; as Clint Smith writes in his book How the Word Is Passed, monuments to the Confederacy were part of “an effort to reinforce white supremacy at a time when Black communities were being terrorized and Black social and political mobility impeded.”

These structures have been powerful symbols of racism, our nation’s original sin. But now time is catching up with them and they have started coming down—sometimes by popular choice, sometimes by force. While more than 700 Confederate monuments are still on display in the US, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s 2020 Whose Heritage? report, which tracks public symbols of the Confederacy across the United States, found that 94 Confederate monuments were removed from public spaces last year. This was more than had been taken down in the preceding four years combined, according to the group.

Fueled by episodes of police violence and institutional racism, many Americans are finally seeing these monuments for the first time not as benign relics but as part of a campaign to dehumanize Black citizens. Cities, counties, churches, and universities are awakening to the bitter significance of these symbols and covering them up, tearing them down, or dismantling them entirely. Where elected officials have been slow to act, ordinary people have taken matters into their own hands.

In the fall of 2020, I became interested in the question: What’s next? That monuments were coming down at all clearly spoke to a shift in Americans’ perception of history, but what would happen to those statues seemed like it might be even more telling—a sign of the nation’s future.

Left: The Athens Confederate Monument on the main drag in front of the University of Georgia’s campus. Installed in 1872, the base of the obelisk listed names of local Confederate soldiers who were killed during the Civil War. Conversations began about moving the monument in 2015 after the Charleston church shooting. After George Floyd’s death, it became a rallying point, with protesters calling for it to be removed. The mayor agreed, and Athens-Clarke County commissioners unanimously approved moving the obelisk in June 2020. [Photo: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock]

Center: Nothing now sits in the monument’s former spot. The mayor proposed a $450,000 plan to relocate it close to the site of one of Athens’ few skirmishes during the Civil War, at Barber Creek. Following that plan, the structure now sits on the old Timothy Road on-ramp, a dead end road visible from an interstate bypass loop.

Right: Georgia is one of a slew of southern states that have a monument preservation act on the books. But on August 10, 2020, workers finally started removing the memorial from its prominent location between historic downtown and the University of Georgia. Before it was relocated, it lay disassembled in a field on property owned by the Athens-Clarke County government.

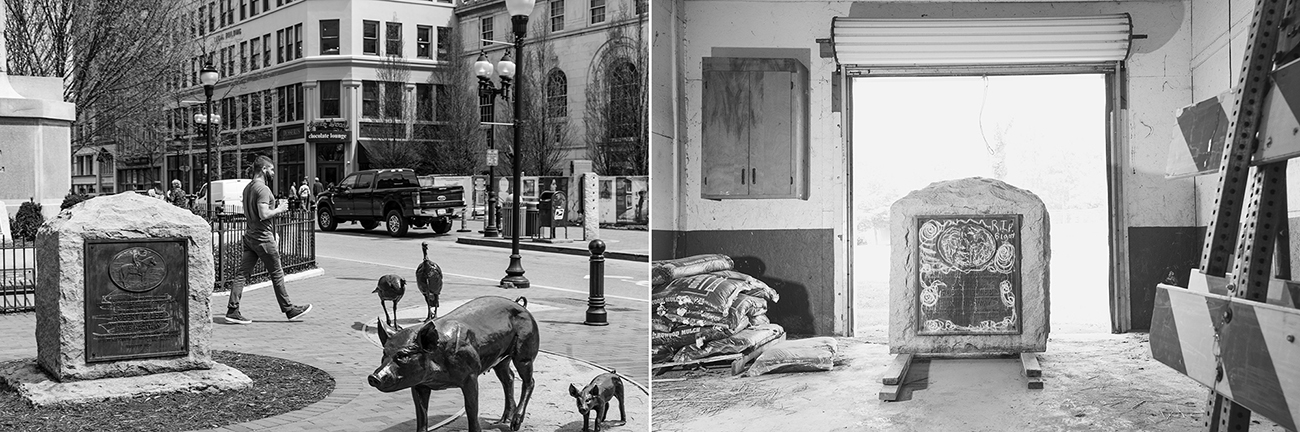

Earlier this year, in April, I started a five-week, 7,300-mile road trip through the South to document Confederate monuments that had been taken down since George Floyd’s death the previous spring. My goal was to create a record of an unraveling—this moment in time when long-held narratives about Southern pride and the memorialization of Civil War “heroes” are literally being knocked off their pedestals. I’m photographing the spaces where the monuments once stood, as well as where they’ve ended up. I’m also pairing these photos with archival images of the monuments, sometimes commemorated on postcards, other times in state and university archives, or in the Library of Congress.

Some cities in Alabama, North Carolina, and Texas have relocated their monuments to Confederate graveyards or local museums. Other cities in Georgia and Florida have moved them out of the public eye and onto private property. And many more have hidden their monuments away in shipping containers, warehouses, storage sheds, public works facilities, city impound lots, a prison maintenance yard, and other “secure undisclosed locations.”

At Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland, community relations and preservation manager Chris Haugh decided not to wipe away the markings protesters had left on a statue of a Confederate soldier that was toppled, beheaded, and tagged with red spray paint. It marked the burial ground of 408 unknown Confederate soldiers who died on July 9, 1864, at the nearby Battle of Monocacy. The monument is history, he said, but so is the paint and other damage. “That’s history, too.”

With that remark, Haugh captured the story I want to tell. It’s about the moment we began to reject the cruelty and white supremacy of once-revered men—and about what comes next, what’s worth preserving, and why.

Left: On June 11, 2020, less than 30 minutes after the Gadsden County commissioners unanimously agreed to remove and relocate the Confederate statue in front of the county courthouse in Quincy, Florida, a crew was on scene to remove it.

Right: The monument is now being stored underneath a tarp in a maintenance yard at the at the Quincy Correctional Institution (also known as the Quincy Annex), behind razor wire and a securely guarded chain link fence.

Left: The DeKalb County Confederate Monument was a 30-foot stone obelisk erected in front of the former county courthouse by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in Decatur, Georgia, in 1908.

Center: A DeKalb County judge ordered its relocation after the city argued it would become a threat to public safety during recent protests over George Floyd’s death. He ordered it removed by midnight June 26, 2020. The building now houses the DeKalb History Center Museum, and historians and local officials have talked about installing a statue of the late civil rights activist Georgia Rep. John Lewis in its place.

Right: The monument currently lies in storage in a county maintenance facility, and some of the protester’s graffiti still remains.

Left: The Nash County Confederate Monument in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, was sponsored by Colonel R. H. Ricks, a Rocky Mount native and Confederate veteran, who donated funds for its purchase and installation. It was dedicated on May 14, 1917; Governor Thomas W. Bickett delivered the address, and a BBQ dinner was served afterwards. Rocky Mount was the site of Rocky Mount Mills, a large mill complex begun in 1818 that exploited slave labor until 1852. [Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill]

Center: Rocky Mount’s City Council voted 6-1 to remove the monument on June 2, 2020. Crews began removing it on June 29.

Right: The monument has been dismantled and is currently being stored behind a barbed wire fence in the city’s impound lot at the back of a wastewater treatment facility, along with several vehicles, air conditioning units, and two RVs.

Left: The Monument to the Unknown Confederate Soldiers at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland, in 2012. [photo: Pollockdog]

Center: The life-size statue of an unknown Confederate soldier was toppled from its base, beheaded, and spray painted by protesters. It was discovered on the morning of June 30, 2020, when cemetery staffers showed up for work. The cemetery superintendent says it will likely not be repaired.

Right: The statue is being stored in a maintenance shed on cemetery grounds, tucked underneath a tarp, lying amongst the shovels and wheelbarrows. It’s still got the scars of red spray paint and tar and is broken into pieces from being pulled down.

Left: A view of the statue of a Confederate States solider in front of the Henry County Courthouse in Georgia. Donated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1910, the statue of soldier Charles T. Zachry has an inscription that reads: “To our Confederate soldiers those who fell in fiercest fighting and sleep beneath the soil of every Southern State…May God preserve forever in our hearts, their memory, and in all minds a knowledge of their motives and their cause.” [Photo: Lee Reese/Shutterstock]

Center: The Henry County Commission voted four to one to dismantle the structure in July 2020. While state law prohibits the removal of monuments, the county attorney relayed to commissioners that it does allow for local governments to “take appropriate measures to preserve, protect and interpret” them. It was removed and hauled away on July 28, 2020.

Right: The county bought a used shipping container for $4,200, where it will be stored on a secure, well-lit, security-camera-lined property for the time being.

Left: The Robert E. Lee monument in Asheville, North Carolina, used to mark the route of the Dixie Highway. Upon dedication in May 1926, a representative from the Dixie Highway Committee spoke of the “far-reaching results” achieved in honoring the “memory of the South’s greatest hero, Robert E. Lee” and said the plaques will speak a “silent message through all the coming years.” In more recent years, the marker stood near the center of Pack Square Park.

Right: The marker was removed by contractors for the city of Asheville on July 10, 2020, and placed in storage at a secure facility. The graffiti on it reads, “R.I.P. Bigot.”

Left: Louisville, Kentucky, Mayor Greg Fischer had wanted to remove the statue of Gen. John Breckinridge Castleman for years before it came down. “Although John B. Castleman made civic contributions to Louisville, he also fought to keep men, women, and children bonded in the chains of slavery and touted his role in the Civil War in his autobiography years later,” Fischer said in June 2020. The statue was dedicated on November 8, 1914. [Photo: Aura Ulm/Scene World Imaging–Louisville KY]

Center: Crews took down the statue in Louisville’s Cherokee Triangle on June 8, 2020, after 11 straight days and nights of protests over the police shootings of Breonna Taylor and David McAtee.

Right: The statue is currently stored behind a city building, partially covered, and still wearing the paint that protesters tagged it with. According to the city, the plan is to place the statue at Cave Hill Cemetery, where Castleman is buried.

Left: The Confederate War Memorial of Dallas was a 65-foot-high monument in the city’s downtown that paid tribute to soldiers and sailors from Texas who served with the Confederacy. The monument was dedicated in 1897 and was flanked by statutes of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Gens. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Albert Sidney Johnston. [Photo: Mark Arthur/Wikimedia Commons]

Center: Workers began dismantling the memorial in Pioneer Park Cemetery on June 22, 2020, 16 months after the Dallas City Council voted to remove the monument.

Right: The statues were crated up, and because of its size, the obelisk was removed in pieces. It’s currently stored at Hensley Field, a former US Naval air station in Dallas.

Left: The Spirit of the Confederacy Monument in Sam Houston Park, in Houston, Texas, was unveiled on January 19, 1908. The bronze structure is an angel with a sword and palm branch, standing on a granite pedestal, and the dedication states: “To all heroes of the South who fought for the principles of states rights.” [Courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University]

Center: In 2017, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner created a “task force of historians, community leaders, and department directors to review the city’s inventory of items related to the Confederacy and recommend appropriate action,” according to a press release. They recommended the Spirit of Confederacy Monument and a statue of Confederate soldier Richard W. “Dick” Dowling for removal from city property, but not destroyed. The statues were removed on Juneteenth last year.

Right: After more than a century in Sam Houston Park, the Spirit of the Confederacy statue was moved to the Houston Museum of African American Culture to educate visitors about racism in America and reclaim the narrative, according to museum CEO Emeritus John Guess, Jr.

This project was funded in part by the Pulitzer Center and a grant recipient of the 2021 W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund.