As of this writing, 695 people have been charged for federal crimes related to the January 6, 2021, Capitol breach—crimes motivated by the lie that Joe Biden won because of nationwide election fraud. Of those 695 people, not one has been charged with sedition, defined in the US Code as two or more people conspiring to “overthrow, put down, or to destroy” the government, “prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law,” or “by force to seize, take, or possess any property of the United States.”

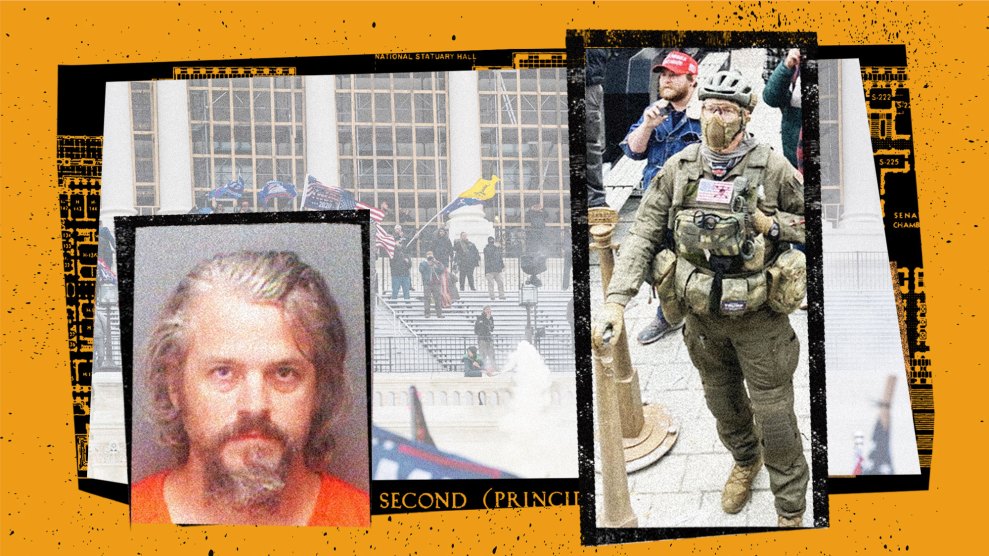

January 6 defendants came armed with bats and bear spray and stun devices and guns and zip ties, aiming to overthrow the election by any means necessary. They called for the execution of the vice president. They assaulted law enforcement, bludgeoning officers with American flagpoles and police barricades. They stormed the Senate floor, stole mementos, and seized government files. They told us what they were there to do—for weeks ahead of time, in some cases—and they very nearly did it.

But no one has been charged with sedition, because America does not talk about violent expressions of white supremacy as sedition. Even when it manifests as a coup against America itself.

Not every person who stormed the Capitol is enrolled in a white supremacist group, but one does not need to avow white supremacy to be its surrogate. What other ideology imbues a mob with the power to besiege the citadel of American democracy and attempt to usurp an election, all in the name of “patriotism”?

“I was listening to Infowars and I was, like, getting patriotic,” said Daniel Rodriguez, who tased DC police officer Michael Fanone during the breach. “We thought we were being used as a part of a plan to save the country, to save America, save the Constitution, and the election, the integrity.” Rodriguez, who helpfully described himself to federal prosecutors as a “piece of shit,” was indicted not on sedition but on more technical charges like obstruction of an official proceeding, along with theft and destruction of government property.

“My story is just that we thought that we were going to save America, and we were wrong,” claimed Rodriguez.

Yet his story is part of an American tradition that casts white supremacy as well-meaning patriotism gone awry, instead of as an ideology antithetical to our best aspirations. But “negro sedition,” as one 1919 newspaper put in the headline of an article warning of “physical…opposition to the government,” has always been viewed as anti-American. Take George Ware, an aide to civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael and an organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In August 1967, Ware was arrested in Tennessee on a warrant charging him with sedition for comments he’d made at a Black school in Nashville: “Black people must achieve power by whatever means necessary, including violence.”

A week after Ware’s arrest, Rep. William Cramer, a Republican from Florida, spoke before Congress in support of HR 421, also known as the “anti-riot bill.” “Outside agitators are using interstate commerce to incite or encourage riots and apparently on a planned, premeditated basis,” he said, assailing Ware and Carmichael as “symbols of the revolution and rebellion that many others are preaching and practicing.”

A grand jury declined to indict Ware, but the appraisal of Black dissent as sedition that landed him in jail for a week has not waned. In the aftermath of protests over George Floyd’s murder, Trump Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen suggested charging protesters with sedition, highlighting a hypothetical example of a group that “has conspired to take a federal courthouse or other federal property by force.”

Even being white does not provide full protection against sedition charges—especially when the white person is advocating for Black Americans. In 1835, Reuben Crandall, a white New York physician and alleged member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, was arrested in Washington, DC, for publishing and circulating material pushing “seditious libel and inciting slaves and free blacks to revolt.”

One newspaper warned that Crandall was “exciting the minds of negroes against whites”; another demonized him as a harbinger of violence toward white citizens. After his arrest at the hands of district attorney and “Star-Spangled Banner” composer Francis Scott Key, a lynch mob gathered. Quick intervention by the mayor saved Crandall’s life, but the crowd still got its fix by launching a multiday assault against the city’s free Black people.

When Crandall’s trial began, the Sedition Act of 1798—created to prosecute critics of Federalist policies—had long since expired. That did not stop Key from indicting Crandall on five counts of seditious libel, claiming he had violated common law. It was the first time an American had been charged with sedition for inciting insurrection among Black people, enslaved or free.

Crandall was eventually acquitted, but not before spending eight months in jail and contracting a fatal case of tuberculosis. During the trial, Key asked the jurors to understand the threat of anti-slavery literature: “What are these writings?…They declare that…we have no more rights over our slaves than they have over us. Does not this bring the constitution and the laws under which we live into contempt? Is it not a plain invitation to resist them?”

After months of smearing election administrators in predominately African American cities, Trump took the mic at the rally just before the Capitol siege to issue a similar, if less articulate, plea to his disciples: “If we allow this group of people to illegally take over our country because it’s illegal, when the votes are illegal, when the way that they got there is illegal, when the states that vote are given false and fraudulent information.”

Using a string of euphemisms for Black vote, Trump spread racist lies. “The problem is Fulton County, home of Stacey Abrams,” he said. “Why wouldn’t they let us verify signatures at Fulton County, which is known for being very corrupt…They go to some other county where you would live…We won’t have a country if it happens.” (Note his use of “we” and “you” and “us.”) “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore,” Trump said. “After this, we’re going to walk down and I’ll be there with you…we’re going to walk down to the Capitol.”

When the rioters arrived at the Capitol, they, like Trump, granted no legitimacy to ballots cast for Biden by Black Americans. “I voted for Joe Biden,” Capitol Police officer Harry Dunn recalled telling insurgents as he confronted them inside the building. “Does my vote not count? Am I nobody?” He was met with jeers. “You hear that, guys?” he remembers a woman wearing a pink maga shirt shouting from a mob of about 20 rioters. “This nigger voted for Joe Biden.”

No one had ever called officer Dunn that word while he was in uniform until it was done in the name of patriotism by rioters carrying banners bearing memes and symbols of white supremacy. There’s a consistency in calling Colin Kaepernick a traitor for kneeling to protest police brutality during the National Anthem and calling officer Dunn a “nigger.” The people who say such things believe they alone are the true adherents to the spirit of the lyrics written by Francis Scott Key.

And what can happen when sedition charges are brought against white people? In 1987, Frazier Glenn Miller Jr., the founder of the Carolina Knights of the KKK and the White Patriot Party, was indicted for conspiracy to acquire stolen military weapons, robbery, and the attempted assassination of Southern Poverty Law Center co-founder Morris Dees. Miller made a deal with federal prosecutors that allowed him to escape sedition charges. But in exchange for a five-year sentence (he served only three), Miller agreed to testify against 14 other white supremacists who would be charged with sedition in a 1988 trial in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Defendants included Richard Snell, who was already in prison for the murder of a pawn shop owner whom Snell had mistakenly thought to be of Jewish descent, as well as the slaying of a Black Arkansas state trooper. (Snell also had a major role in perpetuating false drug-running conspiracy claims that swirled around Bill Clinton.) Three other defendants were leaders of white supremacist groups: Robert Miles, former grand dragon of the KKK in Michigan; Richard Butler, head of an Idaho Aryan Nations chapter; and Louis Ray Beam Jr., a former grand dragon of the Texas Klan. Prosecutors sought to prove that, among other things, 10 of the defendants were guilty of seditious conspiracy, and five had plotted to murder a federal judge and an FBI agent as part of a plan to establish a white nation in the Pacific Northwest.

The prosecution had 113 witnesses and FBI wiretap transcripts capturing the accused coordinating about stockpiling weapons and conducting armored car robberies, assassinations, and municipal sabotage. Before the verdict, the judge told the jury, “The fact that you may think it was impossible for the defendants to overthrow the government is not a defense to the charge.”

Despite that instruction and mountains of evidence, the 14 white supremacists were acquitted by an all-white jury. One juror went on to marry a defendant; another told a reporter he agreed with many of the white supremacists’ ideas. But what may have sealed the acquittal was that the jury did not find the argument that the defendants were dangerous credible. In other words, they did not believe white supremacy was a coherent pathway to topple the American government—or they did not care if it was.

Miller’s brush with the law left him unchanged; in 2014, he would be arrested for murdering three people in an anti-Semitic attack in Kansas. Snell was executed for his earlier charges on April 19, 1995, the same day Timothy McVeigh blew up Oklahoma City’s federal building, which Snell had previously plotted to bomb himself. While McVeigh, also a white supremacist, was indicted on 11 counts, sedition wasn’t one. He was executed in 2001.

If those who assaulted the Capitol are not charged with crimes that equate them as anti-American, what, in the name of America, might they do next?

Republicans who tolerate claims of a rigged election may not espouse allegiance to the Capitol insurrection itself, but they display alignment with its ends. Their gambit is that Trump and his disciples are their political life force—something to pledge fidelity to even if it means the obliteration of democracy, the Constitution, and the star-spangled banner. Here we might remember another thing Francis Scott Key said to the jury in Crandall’s trial:

“All men,” he told them, “must be supposed to intend what it is the evident tendency of their doctrines to accomplish.”