Arianna Anderson had just gone into labor with her fifth child in March 2021 when a bathroom pipe burst. She scrambled to pack for the hospital and, with her husband working out of state, shuttle her young children off to a sitter. Water rushed from a cabinet, pooling on the floor. “Can you imagine? My water was breaking, and there was water coming from underneath the sink,” Anderson recalls. By that point, her four-bedroom, 100-year-old rental house on the 33rd block of Colfax Avenue in north Minneapolis’ McKinley neighborhood had become the starring villain of her life.

Its issues were myriad, its pestilence almost cinematic. During colder months, it lost heat. In the summer, its mold thrived as Anderson’s 7-year-old son fought bloody noses and asthma attacks. In the autumn of 2021, she says a swarm of more than 60 wasps nested in the kitchen, emerging with a vengeance when she cooked. The family kept a butter knife in the upstairs bathroom to jimmy the door each time the knob fell off. (Firefighters once had to come free her son.) When she returned from the maternity ward with her infant daughter, she discovered fallout from the burst. “There was thick mold,” the 37-year-old says. “So I had to bring a new baby home to that.”

A stay-at-home mom, Anderson has been renting the house for about seven years at just over $1,000 per month—with the help of a Section 8 housing voucher—from HavenBrook Homes. Now a subsidiary of private equity firm Pretium Partners, HavenBrook bought the house along with roughly 200 other single-family units across north Minneapolis after the 2008 subprime lending crisis triggered thousands of foreclosures. Renters complain that the company neglects its properties—HavenBrook has been cited more than 200 times for violating Minneapolis housing laws since 2018—and serially charges hidden fees. (On January 10, 2022, the city council revoked two rental licenses held by HavenBrook.)

“In north Minneapolis, [developers] come into our community, they buy up these homes, they do patch work, they get tenants in—and then they sell it for more money,” says Anderson, a lifelong Twin Cities resident. “They don’t give back to our community.”

While Anderson never really considered herself a political activist, as her anger with her landlord grew, so did her inclination to do something. Together with the local nonprofit United Renters for Justice, Anderson began lobbying for the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA)—a proposed ordinance under city council consideration that she believes would help prevent companies like HavenBrook from buying and neglecting the city’s dwindling supply of affordable housing.

TOPA would require many property owners to notify tenants in writing of plans to sell their building, and give them the right of first refusal to purchase it. For tenants who can’t afford to buy their home, the policy would allow them to assign their purchasing rights to a third party vetted by the city, ostensibly reducing the likelihood of a slumlord or hedge fund swooping in to buy it.

Even before the pandemic housing market pushed rents up by a national average of 12 percent, the poorest renters in America were reckoning with a steady rise in mean housing costs—18 percent since 2017. Cities that have toyed with opportunity-to-purchase reform consider it just one of several options that could help keep tenants in their homes amid ballooning rents. “During Covid, we saw what I would describe as a proliferation of these investment firms buying up single-family homes with the explicit intent of either flipping them or renting them,” says Jeremiah Ellison, a city council member and bill sponsor. “I think [TOPA] is a strong option to protect north Minneapolis from investors who really just see an opportunity to seize on cheap real estate in our community.”

While not as widely known a policy as rent control, similar opportunity-to-purchase bills have cropped up in jurisdictions across the country as deepening socioeconomic inequality puts wider homeownership out of reach. In 1980, Washington, DC, was the first city to pass such a law, which remains a national blueprint; a local think tank found that between 2002 and 2012 the policy helped keep an estimated 1,400 units more affordable. Legislatures in at least 10 jurisdictions have since enacted some kind of opportunity-to-purchase reform, including Chicago and San Francisco. Some of those policies, like San Francisco’s, only give the right of first refusal to qualified nonprofit housing developers for multiunit apartments; others, like the one passed in Minnesota in 1991, apply solely to residents of manufactured home parks. In Minneapolis, the measure would apply to most property owners with more than five units. Berkeley, California, and New York state are currently considering similar opportunity-to-purchase laws.

An Urban Institute report from June found that the Twin Cities metro area has the nation’s highest racial gap in homeownership, a trend the study largely credits to the influx of private equity firms that gobbled up single-family homes in lower-income neighborhoods. Investment firms like Pretium, Apollo Global Management, and Cerberus own more than 1,000 rental properties in Minneapolis with fewer than four units, including single-family homes; most recent multiunit building sales have been to national companies. (A Pretium spokesperson told Mother Jones it had “invested more than $46 million in renovations and maintenance to address pre-existing conditions” since acquiring HavenBrook’s properties last year, and denied “that we have in any way contributed to housing inequality issues in Minneapolis.”)

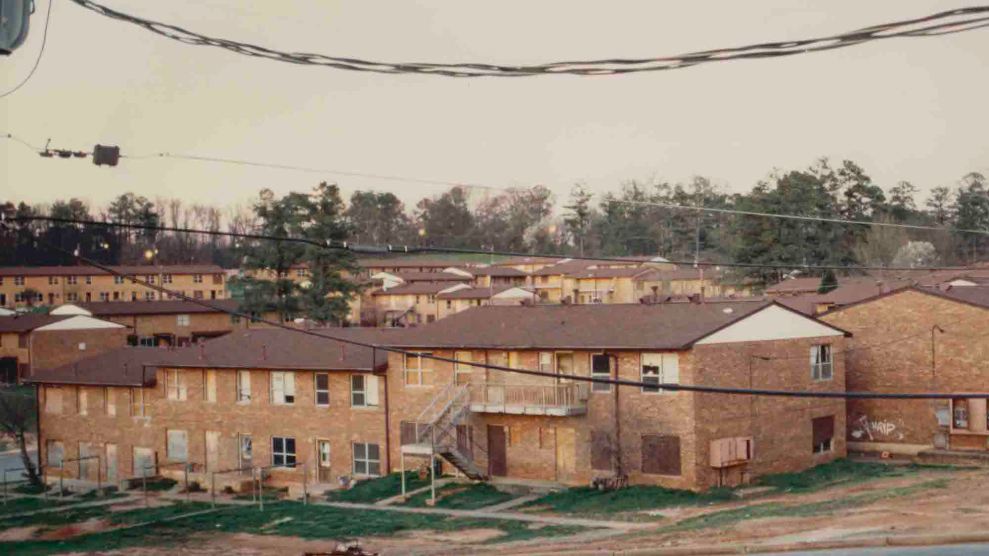

Between 2000 and 2018, the homeownership rate among Black residents in the counties housing Minneapolis and St. Paul dropped 10 percent. Over roughly the same period, Folwell, a neighborhood adjacent to Anderson’s, went from 23 to 53 percent renter-occupied. More than three-fifths of white Minneapolis residents own their homes, while only about one-fifth of Black residents do. The collective impact, says Steve Fletcher, a former councilmember and an original co-sponsor of TOPA, is “a real risk of investment capital shifting what the city feels like and who the city is for.”

With those trends underway, advocates argue that it’s the right time to pass such a measure. “There’s an opportunity here to get ahead of it,” says Jennifer Arnold, co-director of United Renters for Justice. “We’re not at the crisis point that they are on the coasts.”

A preliminary study of the proposed ordinance by the city’s economic development department indicates that it would apply to roughly 30 percent of Minneapolis renters living in small buildings—and every renter living in an investor-owned property. Even if they can’t afford to buy their homes should they ever go up for sale, the city’s current TOPA draft would allow them to assign their purchasing rights to qualifying organizations—companies, nonprofits, or even the city itself. The process would give the renters a bargaining chip, with potential commercial buyers incentivized to appeal to existing renters by offering things like long-term affordability covenants, rent stabilization agreements, or better building maintenance rules.

Under the law, tenants “don’t get it at a discount. They’re not guaranteed the building,” says Ellison, who is the son of Keith Ellison, the state’s attorney general and a former member of Congress. “But the building can no longer kind of be sold right underneath them without them having an opportunity to really be involved.”

Minneapolis housing activists have put together a string of recent victories—from a 2018 council ban on single-family zoning to a successful November 2021 ballot measure paving the way for new rent control. The city’s lawmakers have been formally studying how to implement opportunity-to-purchase reform since at least 2019; the council’s housing committee directed staff to begin drafting a bill in March 2020.

But in the wake of a summer of protests spurred by the May 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, half the city council was voted out, including three of TOPA’s original four sponsors.

“It definitely hurts…to not have my co-authors here to shepherd this process along,” admits Ellison, the only one to win reelection. “I’m definitely going to be feeling that.” But the same election saw voters approve the rent control initiative and elect three democratic socialists to city council, giving hope to lawmakers working to ready a version of TOPA for a vote early this year.

Like all great movie villains, Anderson’s home has wormed its way in to her heart. She sees so much potential in it, if only the landlord would invest in repairs. She dreams about how the new law could help her buy it and rent it out at an affordable rate to a family who needs it, or simply help her family stay in the neighborhood she adores. “When you own something, you take better care of it,” she says. Of TOPA’s potential to promote homeownership, she adds, “I think it gives people a sense of pride and a sense of meaning. And it would add value to our community.”