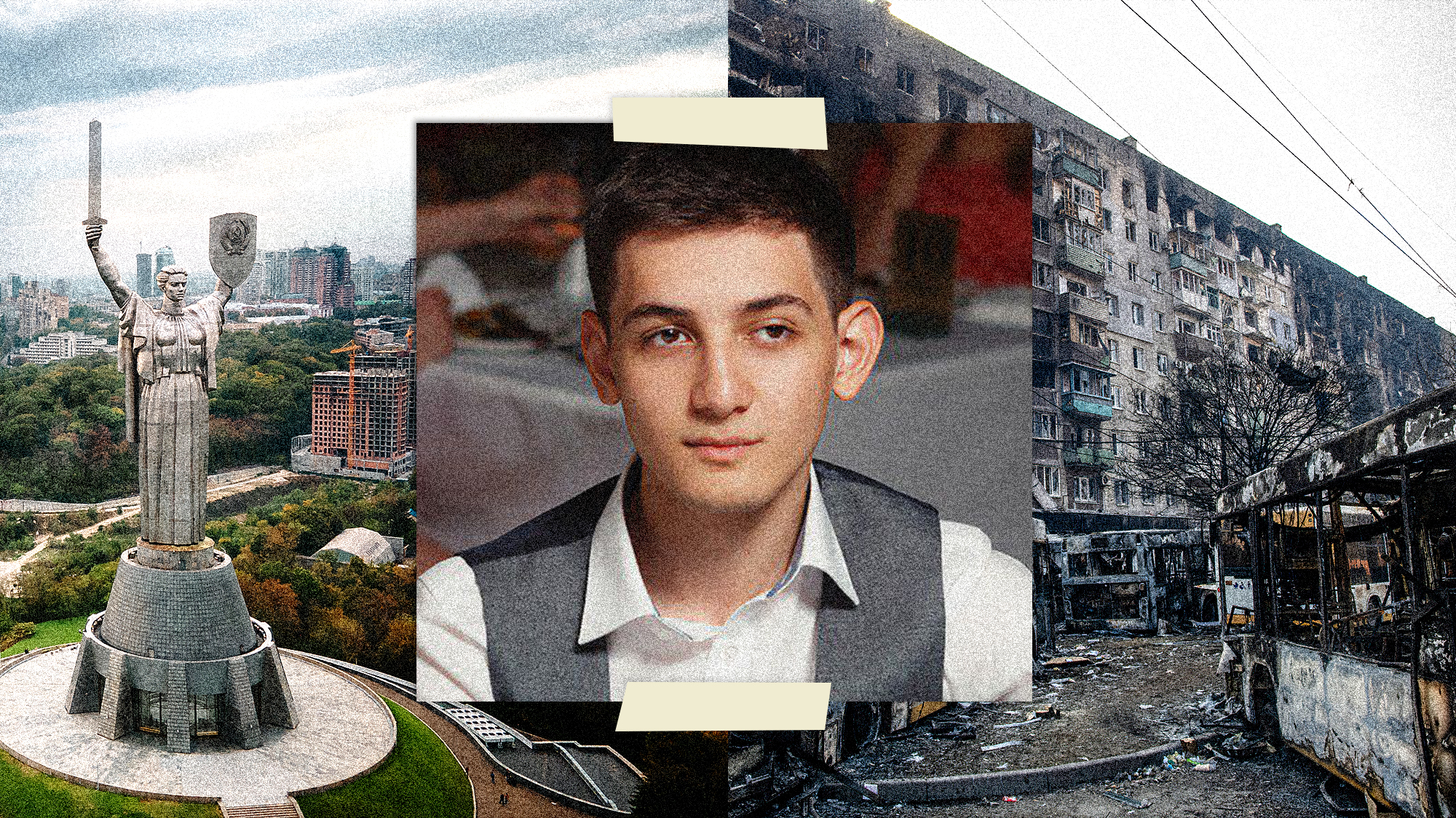

A week before Russia invaded Ukraine, Azad Mamedov’s father, feeling the war could break out soon, had asked him to return home from college to be with the family. Azad, a 19-year-old second-year student of economics in Kyiv, left for Dnipro, a city of one million people about 300 miles southeast of the capital. On February 24, after explosions shattered the peace of Dnipro, Azad, his parents, and his sister escaped to the family’s country home, in a small village 20 minutes outside of town. In the weeks since Dnipro has become a humanitarian center, and Azad returns to the city regularly, volunteering to help the tens of thousands of refugees coming from other parts of Eastern Ukraine. Azad has been journaling and writing poetry about the war and his experience. I spoke with him on WhatsApp. This conversation has been translated from Russian and edited for length and clarity.

When Everything Changed:

At 5 a.m. on February 24, I woke up from explosions. There were three or four of them. There were queues in stores and at gas stations everywhere. It was impossible to find food. Everyone was leaving but didn’t know where to go.

We arrived at my family’s country house and began to somehow come to our senses. The only thought I had was that it would not be for long. That we would go back to the city, to Dnipro, a couple of days later.

When we did go back in early March, the city was half empty. My friends and almost all my acquaintances had left. People just left everything behind. My girlfriend was in Ivanovka, a village the Russians captured. Only today, a month later, she wrote to say she was alive. She said she was fine, and that she would be out of touch for a while.

After 10 days in the city, we started to get used to the explosions and the air raid sirens. It’s terrible. Sometimes even when the wind blows or a motorcycle drives by, you think it’s a rocket. When we hear rockets, we immediately go to the basement until the sirens end. On average, we stay there for about an hour. Every day we have bombings. It’s hard for everyone now.

My Life, Before and After:

Before the war, I used to study for half the day and then go downtown to see my friends. We would go to a concert or listen to poetry. On weekends, I had meetings for a project to make students and universities in Kyiv become environmentally friendly. We were planning on holding a festival in the summer, and we had chosen the site three days before the war. More than 3,000 people were expected but now it’s been canceled.

Azad at a conference in Kyiv in 2021 holding a “Youth for Climate” sign

Photo courtesy of Azad Mamedov

Today, I worked at a volunteer center. At 4 p.m. there were sirens, and we went to the shelter and sat for two hours. I work almost every day at the headquarters with my friends. Students are not accepted into the army. We have many who wanted to serve, but they are denied. So, helping refugees and the military helps me stay sane. When you see how grateful people are to you…they see in you a ray of light that helps them.

Many universities are restarting now. We will start studying online on April 4. Since we are behind and going off schedule, our coursework will be more loaded than usual.

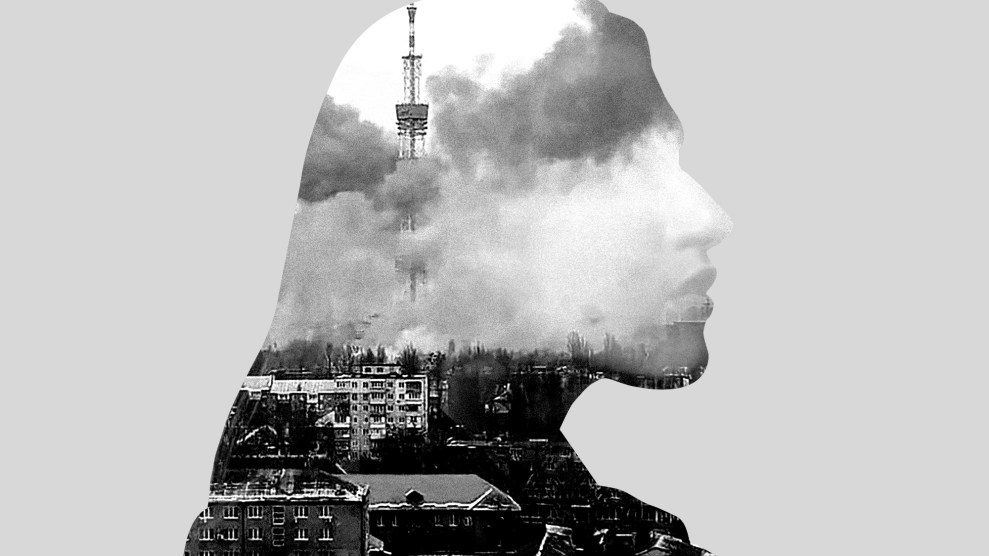

Humanitarian center in Dnipro

Photo courtesy of Azad Mamedov

I have been writing poetry for three years, reading books, and acting. In Kyiv, we shot a short film before the war. My friend is a director and he invited me to play one of the main roles. The essence of the story is how the city draws you in and then just as quickly can spit you out. We started in mid-February and only filmed a couple of scenes. Now, I think we will start shooting a film about the war. We discussed three storylines in which each story is about the path of a single person: someone who runs away leaving with nothing, another who is richer and forgets their homeland, and one who stays to help.

This is our motherland. We plan to stay here. It’s better to help here than go somewhere else and be inactive.

I’m hoping for the best.

For a few days in March, Azad also kept a journal. He shared his notes with Mother Jones:

March 5

Today, getting up at 11 as usual, I opened the phone to watch the news. Today was the first day that Kyiv and Kharkiv were not bombed, a fact that caused both joy and misunderstanding. Why is it so quiet today? Could it be the calm before the storm?

Today we drove to the city. The city feels half dead. Everyone has either left or is sitting at home. The feeling of a half-empty city causes mixed emotions, but it leaves a bright moment of understanding that everything that connected you with this city is leaving at the same moment. You don’t have time to really understand why exactly.

The joy of entering our apartment overwhelmed me. Seeing your bed where you previously slept, and the realization that such simple things have become dear to you. Things that you did not notice in ordinary life. Today I enjoy the fact that I can sleep on my bed and know that I am safe.

March 6

For the first time in two weeks, I was able to sleep well. The pleasure with which you get out of bed, and the sense that today you can imagine that everything seems to be like it was before. But the phone brings you back to reality.

A friend called me and said that her best friend was killed by the Russians in front of her mother and seven-year-old daughter near Kyiv. Honestly, lately, there have been so many stories about how civilians are being killed and this leaves a mark. Probably we will also be frightened by every rustle with the fear of wondering if this is a bomb.

Our generation has known the horror of war. The fear when you wake up in a bunker from explosions and do not know if you will survive during that day, the fear that you do not know where you will spend the night, and the fear when a friend does not answer you for 10 minutes and you can think only about the worst.

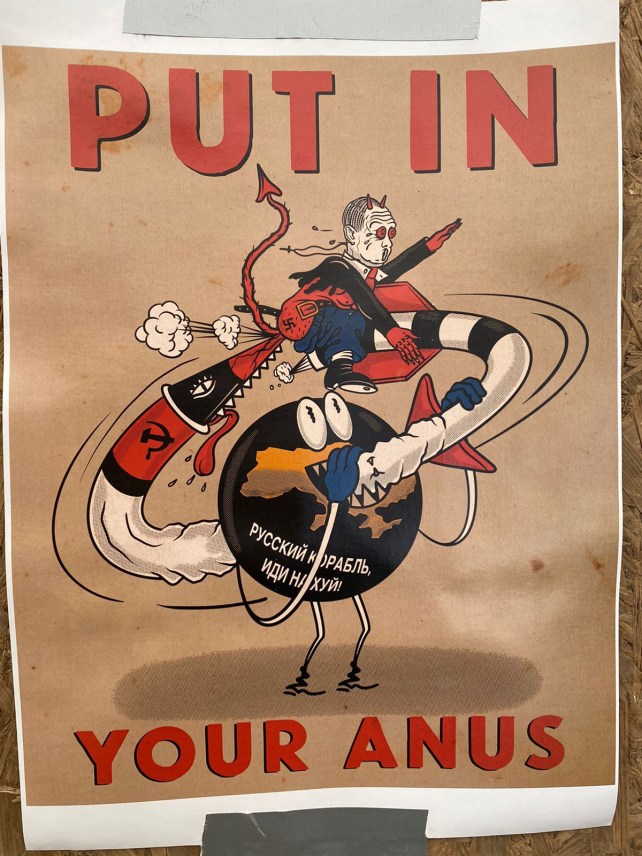

Poster at a humanitarian center in Dnipro

Photo courtesy of Azad Mamedov

March 7

Today delegates from Ukraine and Russia met. We think about what to give [my mother and sister] on March 8 [for International Women’s Day]. Everyone says that the best gift on this day is peace.

I called friends, many left their cities, leaving their dreams and hopes for the best there. When leaving, they understand that returning will not be to their old houses, which were not as important as they will be when they return.

Today, I also thought about the question, is it possible to call a person a patriot who screams about the horror of war while he is abroad and living in good conditions? Just as everyone is hoping for peace, everyone says and reassures themselves that soon everything will end and will be as it was before. But everyone understands, although they do not want to admit it, that there will never be a “before” again.