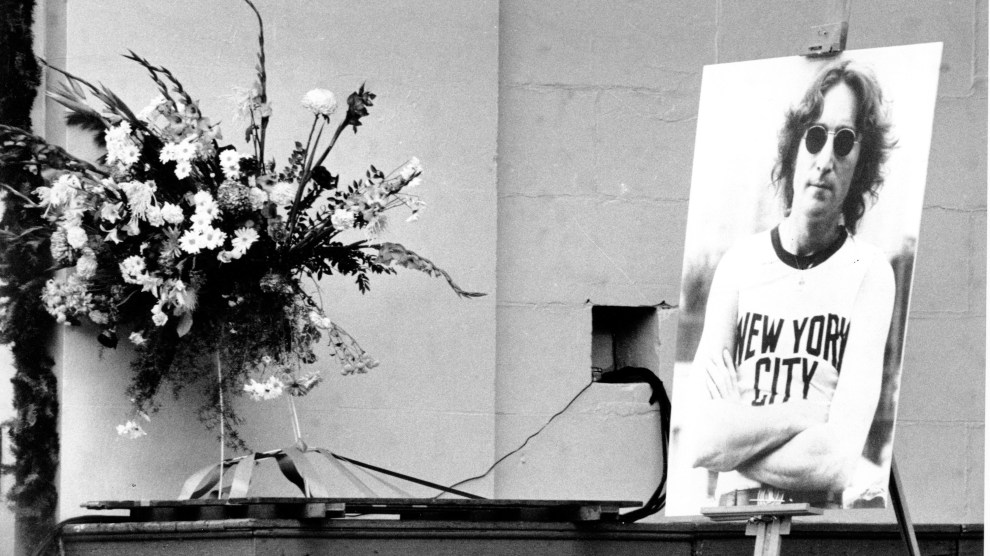

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

After high-profile mass shootings, Republican officials and gun lobbyists always point to mental illness as the cause and call for keeping firearms away from dangerous people. “We as a society need to do a better job with mental health,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said at a press conference in late May after a teen used an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle to murder 19 children and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde. Abbott also emphasized that 18-year-olds have been allowed to buy “long guns” in Texas “for more than 60 years.”

Blame on mental illness as the fundamental cause of mass shootings is unsupported by evidence and highly misleading. Extensive case research shows that, despite popular myth, mass shooters are not insane people who suddenly “snap.” But such rhetoric has long served as a way for politicians to distract from strong bipartisan support among Americans for more stringent gun laws, including comprehensive background checks for gun buyers.

Still, a range of behavioral and mental health problems factor into mass shootings and other forms of gun violence, and that speaks to the potential of a specific policy for restricting access to firearms: extreme risk protection orders, known as red flag laws. Federal funding for states to implement these laws is a significant component of the bipartisan gun bill now moving through the Senate.

A civil procedure currently used in 19 states and the District of Columbia, red flag laws allow police, family members, and in some cases other individuals to seek a court order to temporarily prohibit guns for people deemed by a judge to pose significant danger to themselves or others. Most of the 19 states adopted this policy in the past five years. Now, new research shows that California’s red flag law has been effective in helping to prevent gun violence—including 58 threatened mass shootings.

A study from the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California-Davis, published this month in the peer-reviewed journal Injury Prevention, examined a total of 201 cases in California during a three-year period beginning in January 2016, when the state’s policy went into effect. None of the 58 individuals who threatened mass shootings committed such attacks after they were subjected to what California calls “gun violence restraining orders.” Nor did any of them later commit suicide using a gun, which is both a major factor in mass shootings and the leading type of gun death annually in the United States. Red flag laws appear to help prevent suicide in general; 40 percent of the 201 total cases involved threats of self-harm, and a quarter of the cases involved threats of harm both to self and others.

The study included 12 cases involving school shooting threats. None of those individuals went on to commit such attacks.

As with the broader prevention work of behavioral threat assessment, it’s difficult to attribute the absence of violence to any particular intervention. The study’s authors are careful not to claim that the court orders were the cause of nonviolent outcomes. But their deeper study of 21 of the 58 cases involving mass shooting threats further suggests that the red flag policy is effective: The researchers found no subsequent gun homicide of any kind in those 21 cases. (The authors told me that they are currently pursuing the same deeper examination of the other 37 cases involving mass shooting threats.)

“Policymakers should being thinking of extreme risk protect orders as important life-saving tools that [have] widespread support among the general public,” says Veronica Pear, an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at UC Davis Health and the lead author of the new study. “Residents of all states deserve to have this option available to them so that they can help prevent firearm violence from occurring in their communities.”

The policy has consistently seen strong bipartisan support among Americans, including gun owners. Its popularity was reconfirmed in mid-June by a Fox News poll.

The UC-Davis analysis points out explicitly that the protection orders from judges are based on behavioral warning signs—communicated threats of violence and other behaviors indicating danger—and that psychiatric diagnoses are not a recommended focus for making the determination. That’s borne out by the study: a clinical diagnosis of mental illness was present in only a fifth of the total cases—a risk factor primarily for suicide—and only 11 percent of cases involved psychosis or hallucination.

This aligns with previous study of rampage shooters. It’s possible that some mass shooters and those who threatened attacks may not have been adequately screened for mental health conditions. But a groundbreaking study of shooters by the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit, whose investigators had unparalleled access to case information, revealed that many perpetrators clearly did not qualify for a clinical diagnosis of mental illness, as a leader of the FBI team told me during my reporting for my new book, Trigger Points.

Among the other findings from the study of 201 cases in California: All but 13 of the subjects were male, and 61 percent of the subjects were white. Four out of five cases involved threats to harm others, and nearly a third included threats against intimate partners. (That underscores the importance of closing the “boyfriend loophole,” another sharply politicized policy included in the Senate bill.)

The funding for red flag laws in the Senate gun bill was a point of contention in hammering out the legislative text. As with the enduring issue of comprehensive background checks, that tension underscored the stark disconnect between what most Americans say they want and the legislative stalemate over guns, long beholden to far-right demagoguery. The bill’s lead Republican negotiator, Sen. John Cornyn, was roundly booed during a speech at the Texas GOP convention last weekend, including jeers of “No red flags.” His fellow senator Ted Cruz characterized red flag laws as “a vehicle to disarm law-abiding citizens without protecting due process.” John Barrasso of Wyoming, the third-highest-ranking Senate Republican, said earlier this month that “there is no role of the federal government for red flag laws,” adding, “Wyoming is never going to pass one.” The National Rifle Association rejects the policy outright, calling such measures a “mortal danger” to gun rights.

But these criticisms fly in the face of mounting evidence that red flag laws could help prevent mass shootings on a broad scale. The California research team is now also part of an ongoing six-state study, whose authors have found 626 cases since 2013 in which extreme risk protection orders were issued by judges in response to credible threats of mass shootings.

Whereas initial research into the policy indicated that suicide could be the most promising area for prevention, the prevalence of mass shooting threats has also stood out. “That caught us by surprise,” Garen Wintemute, a longtime leader of the UC-Davis research program and a coauthor of the new study, told me.

The more recent findings, Wintemute said, have prompted plans for further research into the potential that red flags laws hold for reducing mass shootings. Lawmakers who are authentically focused on preventing the next Uvalde, Buffalo, Oxford High, or myriad other scenes of devastation would do well to pay attention to the growing results.

Update, June 23: The authors of the California study clarified that, to date, they conducted research specifically to confirm the subsequent absence of a mass shooting in 21 of the 58 cases involving such threats. That research into the remaining 37 is pending. They further confirmed that none of the remaining 37 case subjects appears in the Mother Jones database of mass shootings.