On a scale of 1 to 10, Sarah Holzer considered the pain of breaking her tailbone a definite 10. That is, until 12 years later, when, at 27, she went in for her IUD insertion. She was nervous as she waited in the doctor’s office, having heard from friends that it might be painful, but she had been assured at her previous appointment that it would be just a quick pinch. When it came time for the procedure, the nurse held down her shoulders, pinning her to the table, and that was when Holzer realized it was really going to hurt. She ended up blacking out from the pain. Immediately afterward, she threw up. “Once I got an IUD,” she told me, her pain scale changed. “A bone break to me is maybe now like a 2.”

It sounds extreme, but Holzer isn’t exaggerating—and she isn’t alone.

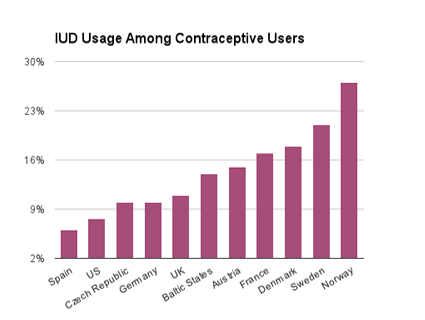

The IUD is one of the most effective birth-control devices on the market, and the copper version is the only widely available nonhormonal option besides barrier methods like condoms or diaphragms. According to the CDC, more than 8 percent of women ages 15 to 49 are using IUDs, or intrauterine devices, as of 2019.

IUDs were initially popular in the US in the 1970s, until problems with the Dalkon Shield IUD led to widespread fear of the devices and the misconception that they were all dangerous. (While there were infections and unintended pregnancies related to Dalkon Shield, IUDs today are considered incredibly safe.) They became widely used again in the last decade, after the Affordable Care Act helped to bring down their costs for many patients. And now, as anti-abortion activists continue their assault on abortion access, IUDs may soon become even more popular—because they can last for up to a decade. Dr. Christina Bourne, the medical director of Trust Women, which runs abortion clinics in Oklahoma and Kansas, estimates she has placed twice as many IUDs in the past month as she has in the past year.

Today, there are five types of IUDs available in the US. To place an IUD, a provider inserts a speculum and then usually uses a tenaculum, a device that resembles a pair of scissors with hooked ends, to stabilize the cervix before inserting the IUD through the opening of the cervix and into the uterus. The process takes about five minutes, but the experience of insertion can be excruciating.

Providers know this process can be extremely painful for some patients, but there has not been enough research on the topic to understand why this is the case. As a result, options on how to treat patients are limited. Aside from recommending that patients pop an ibuprofen beforehand, there are no comprehensive guidelines around how best to make the procedure more comfortable. Some providers use lidocaine gel or local anesthesia, and while a 2019 review found promising evidence that these strategies have the potential to lessen pain, not enough research has been done to make any one method the standard of care.

There are even some gynecologists who prescribe misoprostol prior to an IUD insertion. Misoprostol is a hormonal drug that is used to prevent stomach ulcers, but it is perhaps best known for its use in medication abortion to induce cramping that helps empty the uterus. The rationale is that it could help to dilate the cervix, reducing pain during the IUD procedure. But several studies have shown that the effects of misoprostol to ease the insertion process are insignificant, if it helps at all, and the side effects are often so awful that two days of misery negates any small possibility that the pills might aid the insertion process. Dr. Leah Torres, medical director of West Alabama Women’s Center, says she does not use misoprostol as pre-treatment for IUDs for this reason. “In medicine, decisions regarding interventions should be made weighing benefits against risks,” Torres says. “In this case, the risks—unpleasant side effects—seem to outweigh the benefits.”

Essentially, providers are left to do the best they can with the tools they have, and women are expected to endure the pain, says Katherine Winters, a nurse midwife in Seattle. It is “frustrating,” she says, “that I don’t have better options to provide to people that just want good birth control.”

There are still other barriers to potentially useful methods of pain management. For example, sedation isn’t commonly offered because it is too expensive for many patients and requires medical equipment many clinics don’t have. Laughing gas, which is commonly used in the UK for labor and minor procedures, could be an option, but is not widely used in the United States. Leena Nathan, the medical director of UCLA Community OBGYN Practices, has done IUD insertions on patients in an operating room before, especially when they are already undergoing another procedure, and believes that sedation is a good option for some people. Torres believes moderate sedation should be the default. “In my opinion, that this is not a default practice or option for IUD insertion speaks to the deeply rooted misogyny and patriarchal practices in medicine,” she says. “Outpatient clinics interested in and willing to incur additional costs should include this as an option for IUD insertions.”

Complicating matters further is that it’s not always certain a patient will feel any significant pain. Though Holzer’s ordeal isn’t atypical, it’s also common for patients to feel only slight discomfort, or even have very different experiences of insertions. Patients who have given birth vaginally tend to have an easier time than patients who haven’t because their cervix has dilated; one study estimates that about 17 percent of women who haven’t given birth vaginally experience substantial pain, compared with 11 percent with a previous vaginal delivery. Yet aside from childbirth history, it’s extremely difficult even for experienced providers to anticipate how a patient might react.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists admits that more research is needed. The authors of a 2019 review of pain interventions acknowledged, “In the modern era of medicine, our inability to recommend any positive treatment for pain relief with [IUD] placement creates professional discomfort,” to say nothing of the discomfort it causes actual patients. Yet despite the fact that practically everyone in the field agrees that IUD insertion pain is a giant problem without a good solution, very little work is being done to develop less painful, long-acting, reversible contraceptive options for women. Study after study has found that government agencies like the National Institutes of Health underfund medical research about women. Winters, the midwife, finds this unacceptable. “I absolutely believe that if men were the ones getting IUDs, the procedure would look a lot different by now,” she says.

The looming Supreme Court decision on abortion rights means it’s more important than even to remove barriers from access to contraception. And for people currently making decisions about contraception, the pressure is on.

Beyond the anecdotes of individual providers, research backs up the idea that potential shifts in reproductive policy can drive demand for IUDs. One study found that there was a 22 percent increase in long acting reversible contraception insertion rates in the month following the 2016 election—likely spurred by fears about what the new administration would do to the Affordable Care Act, and thus access to contraceptives, as well as the future of Roe. Many of the fears that led more patients to get IUDs in the wake of Trump’s election nearly six years ago are finally being realized, so it wouldn’t be surprising to see a similar or even greater uptick in patients interested in IUDs now.

The reality that nearly half of all Americans live in states where abortion could be banned would be reason enough to drive more patients to seek out IUDs, but on top of the fears about how to manage an unwanted pregnancy, birth control itself could be the next fight for the anti-abortion movement. As my colleague Kiera Butler has reported, Christian activists who believe that birth control itself is a form of abortion are being bolstered by secular wellness influencers who have begun to promote a view of hormonal birth control as “unnatural.”

IUDs in particular could be at risk because they can stop a fertilized egg from implanting in the uterus and some people against abortion view fertilization as the point life begins. Some IUDs can also be used as an emergency contraceptive, which is another possible target for the anti-abortion movement.

Oklahoma, for one, recently passed an abortion ban that starts at fertilization. And though that bill specifically carved out an exception for emergency contraception and IUDs, it lays the foundation to go further and provides a terrifying example of legislation that calls a fertilized egg an “unborn child,” at a time that comes before the scientific community would generally even consider a person to be pregnant, and at least 9 weeks before ACOG would even call the embryo a fetus. Then just last month, Missouri state Sen. Denny Hoskins said that “anything’s on the table,” in discussing his opposition to the emergency contraception Plan B. This comes after Missouri voted last year to ban state funding for contraceptives like Plan B and some IUDs. Though that language didn’t make the final bill, the Missouri Independent reported that there could be renewed energy for that fight once Roe is overturned.

The irony is that the IUD has been proven to be effective in curtailing abortion rates when access to them is expanded. When Colorado introduced a program in 2008 that removed financial barriers and improved overall access to IUDs, teen birth and abortion fell significantly, and the state avoided nearly $70 million in public assistance costs over five years. If pain weren’t a problem, who knows how many more women would benefit from IUDs? The loss is hard to quantify.

Also hard to quantify is the trauma that many patients experience during insertion—and how that can color a patient’s future health care interactions. When Holzer expressed how painful she had found her insertion, she recalls the physician assistant telling her, “I knew that if I was honest with you that you wouldn’t have actually gotten the IUD.” When Holzer left her doctor’s office, she sat in her car for an hour still reeling. “It made me very distrusting of anything any doctor ever says to me,” she says. “I really haven’t gone to the doctor that much since.”

Additional reporting from Becca Andrews.