Mother Jones illustration; Unsplash; Bob Daemmrich/Zuma

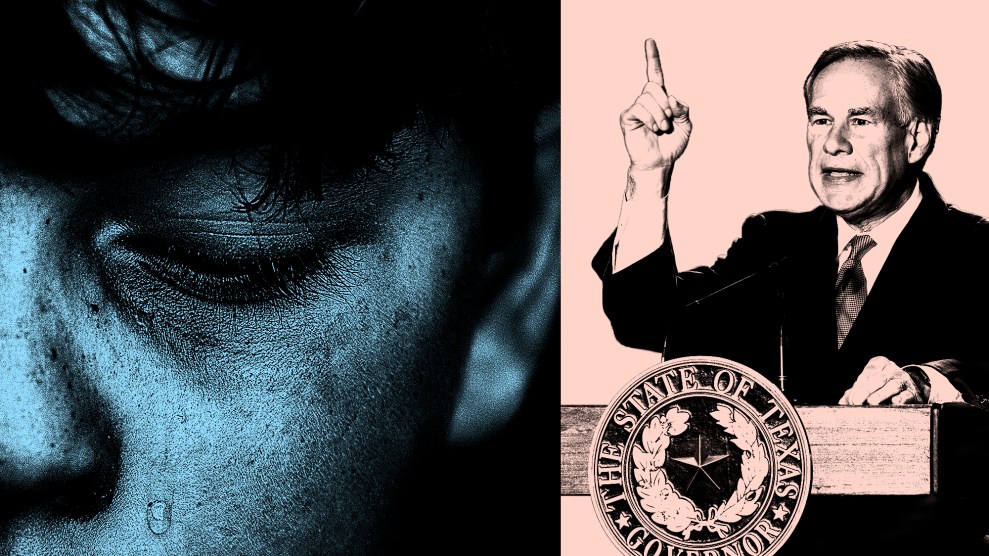

After Texas Gov. Greg Abbott ordered state officials in February to launch child abuse investigations targeting parents who helped their transgender kids get gender-affirming health care, a 14-year-old trans girl became so anxious about the prospect of losing access to her medications that she was pulled out of school and hospitalized for days. Some doctors and pharmacies around the state stopped offering teenagers life-saving puberty blockers and hormone treatments. A mental health provider in Austin abruptly withdrew care from a suicidal trans boy, leaving his parents to sleep on his bedroom floor night after night to ensure he didn’t kill himself. Many families fled the state.

Those are just some of the stories in a legal brief submitted to a state court last week on behalf of two LGBTQ-focused nonprofits and 13 Texas families with transgender kids. The families are begging the court to make permanent a prior temporary injunction prohibiting state officials from investigating parents under Abbott’s order. Although Texas’ Department of Family and Protective Services hasn’t yet ripped any trans children in Texas from their homes and sent them to foster care, the families argue its investigations have already had tragic consequences.

Since Abbott’s directive took effect, the Transgender Education Network of Texas (TENT), one of the nonprofits cited in the brief, has received at least 60 reports from families struggling to obtain health care for trans children. Some doctors reportedly denied prescriptions for kids at the onset of puberty, hoping that it might be legally safer to offer them treatment at a later point. The nonprofit is working with 27 families in two metro areas who could not obtain puberty blockers, reversible prescriptions that give trans kids a chance to explore their gender identity as they grow older while temporarily delaying the puberty changes in their body that could make their gender dysphoria worse. Equality Texas, the other nonprofit in the brief, says kids have been turned away by doctors or denied prescriptions at pharmacies in Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and the city of Garland.

Families say they’re also afraid to get their trans children other types of health care, worried that the kids’ gender identity and medical history might become known to the hospital and be shared with state authorities. According to the brief, when one trans kid went to a hospital for emergency psychiatric treatment, hospital staffers reported the mother to state officials, who accused her of child abuse. In another case, a trans child almost slept in a hallway at a mental health facility because the facility, citing legal risks, didn’t want to admit the kid to a ward. TENT intervened.

“As a result of losing healthcare,” the families in the brief saw their kids experience “a variety of debilitating symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and thoughts of self-harm.” The 14-year-old girl I mentioned, identified as A.P., was so “paralyzed with anxiety” that she was pulled out of eighth grade and had to finish the academic year at home. A nonbinary teen identified as C was devastated when their school cited the governor’s order as a reason to rescind approval of a learning unit about nonbinary gender identities, which the teen had hoped would help bullies at school become more understanding. A 9-year-old started crying when their parents told them to no longer talk publicly about being trans. “The child has since expressed fear of being…put up for adoption, sharing the heartbreaking worry that ‘nobody would adopt me because I am trans,'” the brief says.

Another 9-year-old girl started carrying a laminated business card with her to school and on the playground, stating her name and that she did not consent to speak with any child welfare investigators who might try to interview her away from her parents. The girl developed anxious tics, clearing her throat repeatedly before talking, and her little brother started having nightmares about losing her. Statewide, TENT says that within just one month of the governor’s directive, it received messages from dozens of families whose trans children had mentioned suicide. “Put simply,” attorneys wrote, Abbott’s order “traumatizes children.”

The order has also coincided with transphobic harassment and attacks. After the directive, Equality Texas received hate mail threatening staff members, while protesters came to the premises to yell and swear. False rumors that the Uvalde school shooter had been trans, the group heard, led someone to assault a trans teen in El Paso. One family said their church’s Pride event for children was disrupted by protesters who took the kids’ photos and threatened to report parents to child welfare investigators.

That climate is driving many families out: About 20 percent of the families who previously worked regularly with TENT left Texas after the governor’s order. Equality Texas says about 10 percent of its volunteers, who helped the group by testifying at legislative hearings and other events, also left. Sometimes, this means splitting up relatives. A 15-year-old trans boy identified as N moved out of state with his mom while his dad and younger brother stayed in Texas. The boy had to interrupt his first romantic relationship for the move, and his mom was forced to stop caring for her elderly parents and disabled sibling in Houston. Others stayed in Texas but have “turned down job offers or opportunities to grow their family businesses because they might have to leave at a moment’s notice,” the brief says.

The brief supports a lawsuit filed in March by the ACLU and Lambda Legal, an LGBT rights group, seeking to stop the state’s investigations of families with trans kids. A district court initially granted these groups a temporary statewide injunction to stop the investigations, but in May the Texas Supreme Court pushed back—narrowing the injunction so that it would only block the investigation of one particular family who were plaintiffs in the lawsuit. The next month, the ACLU and Lambda Legal filed a second lawsuit on behalf of three more families. The same district court issued another temporary injunction stopping investigations against two of those families. The court is now considering whether to also extend the injunction to protect any members of the LGBTQ group PFLAG, more than 600 of whom live in Texas.

Abbott’s order is opposed by major medical groups like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association, which say that gender-affirming health care is widely accepted and often life-saving for teens struggling with gender dysphoria. Most trans children begin with a social transition, changing their hairstyle and clothes and going by a new name. At the onset of puberty, they may begin puberty blockers, which are reversible. The next step, hormonal therapy, can cause permanent changes in the body, but older teenagers often start with small doses and build up over time. Surgeries are usually not performed until adulthood.

As the court battles continue, the 13 families who filed their brief last week asked the district court to bring back and make permanent the initial statewide injunction from the first lawsuit. “An injunction is necessary,” their attorneys wrote, to let families like theirs “care for their children’s health, feel safe in their homes and schools, and return to the ordinary joys and cares of parenthood and family life in Texas.”