During his time in the White House, no target provoked as much anger from Donald Trump as the American press. In 2017, he declared, “The press, honestly, is out of control.” In 2019, he called it “truly the enemy of the people.” His reelection campaign sued the Washington Post and the New York Times. Some 500 of Trump’s tweets attacked individual journalists by name, and at one point he accused the Times of “treason.” When Trump and Vladimir Putin—under whose rule some critical journalists have been assassinated—sat down for a press conference at a Group of 20 summit, Trump pointed to the reporters waiting in front of them and joked, “Get rid of them.”

A century earlier, an American administration did get rid of opposition journalism with a ruthlessness Trump would be fiercely jealous of. It closed down about 75 newspapers and magazines, prevented the distribution of specific issues of many more, and put journalists on trial in federal courts. This entire operation was managed from the landmark Washington building that would become, 100 years later, the Trump International Hotel.

Ironically, this wave of repression took place under a president who, on the surface, appeared to be the polar opposite of Trump. Before entering politics, Woodrow Wilson was known as an intellectual: a longtime college professor and the president of Princeton University. But when in April 1917 the United States declared war on Germany, joining the bloody conflict that had ravaged Europe for nearly three years, both the United States and its president revealed a ferocity that few people had anticipated.

It was not that we had previously been a peaceful nation without tensions. There were plenty of these, which often turned violent: between nativists and immigrants, business and labor, and white and Black Americans. But when the United States joined the First World War, it deepened all of these divisions. And a new fault line emerged, between those who thought the war was a noble and necessary crusade, and those—mainly but not entirely on the political left—who thought it was a catastrophic mistake. Among the war’s opponents were most supporters of the Socialist Party, which had won 6 percent of the popular vote in the 1912 presidential election.

The government feared trouble: demonstrations, industrial sabotage, and attempts to disrupt the newly imposed draft. Wilson was as quick as Trump to brand anyone who disagreed with him as traitors. “Woe be to the man or group of men that seeks to stand in our way in this day of high resolution,” he declared on June 14, 1917. Any such opponents were “agents and dupes” of the German kaiser. The very next day, Congress passed the centerpiece of a string of repressive measures, the Espionage Act. (Amended, it is still in effect today, and was used to indict whistleblower Edward Snowden.)

Despite its name, the new law had almost nothing to do with spies. Both opponents and supporters saw it for what it was: a club to smash progressive forces of all kinds. Sen. Lee Overman of North Carolina, for example, a plump, courtly Democrat who once helped filibuster an anti-lynching bill to death, declared that the Espionage Act was needed to prevent propaganda “urging Negroes to rise up against white people.” The act defined almost any opposition to the war as criminal. The penalties were draconian: “a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both.” What could send you to jail for 20 years? The list was so far-reaching that it was a prosecutor’s dream. At risk, for instance, was anyone who “shall willfully make or convey false reports or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the United States.”

Dismaying liberal intellectuals who had previously admired him, Wilson wanted still more. “President Wilson today renewed his efforts to put an enforced newspaper censorship section into the espionage bill,” reported the Washington Evening Star as the Espionage Act was under debate in Congress. Wilson wrote to the chair of the House Judiciary Committee, “The great majority of the newspapers of the country will observe a patriotic reticence about everything whose publication could be of injury, but in every country there are some persons in a position to do mischief.” This clause was voted down, and members of Congress promptly congratulated themselves on having preserved free speech.

However, though it didn’t use the word, the new law did indeed allow censorship. At a time when there was no other way to distribute publications nationally, it gave the postmaster general the authority to declare any newspaper or magazine “unmailable.” That power could not have landed in more dangerous hands.

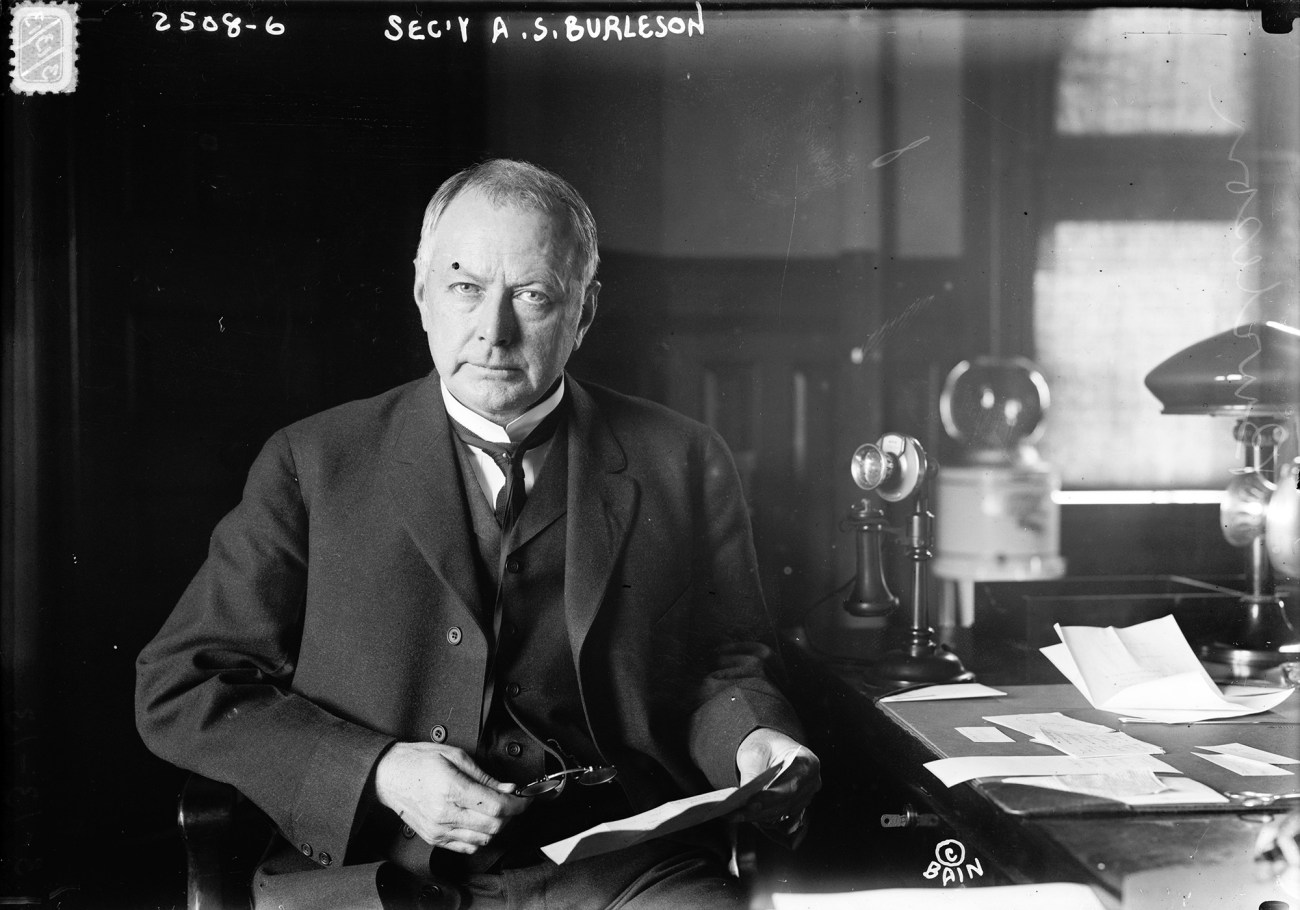

Former Rep. Albert Sidney Burleson of Texas “has been called the worst postmaster general in American history,” notes historian G.J. Meyer, “but that is unfair; he introduced parcel post and airmail and improved rural service. It is fair to say, however, that he may have been the worst human being ever to serve as postmaster general.”

Until the passage of the Espionage Act, two features had distinguished Burleson’s time in that office: his opposition to postal workers’ unions, which he felt were “a menace to our government,” and his zeal for segregation. He was eager to attack such affronts as having white and Black postal workers sorting letters in the same railway mail car, or using the same restrooms (“intolerable”), or having white and Black patrons line up at the same post office window. He segregated postal lunchrooms and ordered screens erected in work areas so white employees would not have their view sullied by Black ones.

Measures like these, incidentally, did not bother Burleson’s boss in the least. The first Southerner elected president since the Civil War, Wilson had a startlingly benign view of slavery, made virtually no protest against the more than 400 lynchings of Black Americans that took place during his presidency, and was fond of telling “darky stories” during Cabinet meetings.

For Burleson, such beliefs were rooted in his background. In the year of his birth, 1863, his father testified in a legal proceeding that he owned “over twenty negroes and over five hundred sheep.” Both his father and grandfather had served in the Confederate army, and in 1917 the postmaster general was seen weeping at the sight of a parade of elderly Confederate veterans.

Now, this arch-segregationist had suddenly become America’s chief censor as well, with powers seldom wielded by any single government official before or since.

One scholar describes Burleson as having “gray and rather cold eyes, and short side whiskers. With his conservative black suit and eccentric round-brim hat, he closely resembled an English cleric.” Wilson and other Cabinet members nicknamed him “The Cardinal.” But while conventional enough, his attire was often in disarray. “Burleson acted the part of a homely, uncouth politician, which he was not,” wrote Treasury Secretary William McAdoo. “In reality he was a gentleman of education and ability. But he had a slovenly way of dressing. His clothes were frequently rumpled and rusty. I think he intended to create the effect that he was no better than the humblest citizen.” Despite this populist surface, Burleson had a taste for luxury. A top-hatted coachman transported him and his wife around Washington in an elegant, two-horse barouche.

Albert Burleson

Bains News Service/Library of Congress

A Secret Service agent in Wilson’s detail found The Cardinal “an extremely sly gentleman. He was so astute and secretive that his left hand never knew what his right was doing.” Rain or shine, he carried a black umbrella that he tapped on the floor or sidewalk while walking, for he suffered from gout but was embarrassed to reveal it by using a cane. He combed his hair forward to cover a bald patch.

Like most who had occupied the job before him, Burleson, who normally dropped by the White House three or four times a week, helped the president he served by artfully dispensing patronage, especially the country’s 56,000 postmaster positions. One Kansas senator, for example, won five postmasterships to distribute in return for voting the way Wilson wanted on a tariff bill. But to Burleson, exercising the virtually unprecedented power to censor the nation’s press was far more exciting.

In his mind, some publications were automatically suspect, especially “those offensive negro papers which constantly appeal to class and race prejudice.” A day after the Espionage Act passed, he instructed postmasters throughout the country to immediately send him any newspapers or magazines that looked suspect. His office was in the Post Office Department headquarters in Washington, the building that several incarnations later would be the Trump International Hotel, where a lobbyist currying favor could stay in the Postmaster Suite for $4,396 a night.

Burleson was on the lookout, he said, for any publications “calculated to…cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny…or otherwise embarrass or hamper the Government in conducting the war.” What did “embarrass” mean? Burleson listed a broad range of possibilities, from saying “that the Government is controlled by Wall Street or munition manufacturers, or any other special interests” to “attacking improperly our allies.” “Improperly”? He knew that sweeping and vague threats inspire fear, and so, when a delegation of lawyers headed by the famous defense attorney Clarence Darrow visited him to demand clarity, he refused to spell things out in any detail.

The first victim of Burleson’s censorship powers, which he flexed before the Espionage Act was even signed, went almost unnoticed. It was the Rebel, a socialist newspaper in Hallettsville, Texas. The Rebel opposed the war, but the postmaster general’s swiftness in barring it from the mail was clearly due to revenge. Calling him “a notorious exploiter of his peons,” the paper had several years earlier exposed how Burleson had managed a Texas cotton plantation that his wife inherited. First, it revealed, he evicted Mexican tenant farmers, replacing them with white farmers; then he leased out the land to the state, which replaced the white farmers with prisoners in striped uniforms living in tents and working under armed guards. The prisoners were routinely whipped when they didn’t work hard enough.

One reason Congress so willingly gave The Cardinal the power to declare something like the Rebel “unmailable” was that this law would not affect mainstream daily newspapers. Not only were the vast majority uncritical supporters of the war, but they were delivered to homes by carriers or sold at newsstands. Most of the publications that depended on the mail were foreign-language papers, opinion journals, and the socialist press.

There were well over 100 socialist publications; three-quarters of American states were home to at least one. Whatever the Allies claimed to be fighting for, most socialists felt, American lives should not be added to the millions already lost; workers of different countries should be battling the capitalists and not each other. That gave Burleson the excuse to go after their periodicals, and he did so with a vengeance, banning 15 from the mail within a month after the Espionage Act passed. Before long, he’d shut down dozens more.

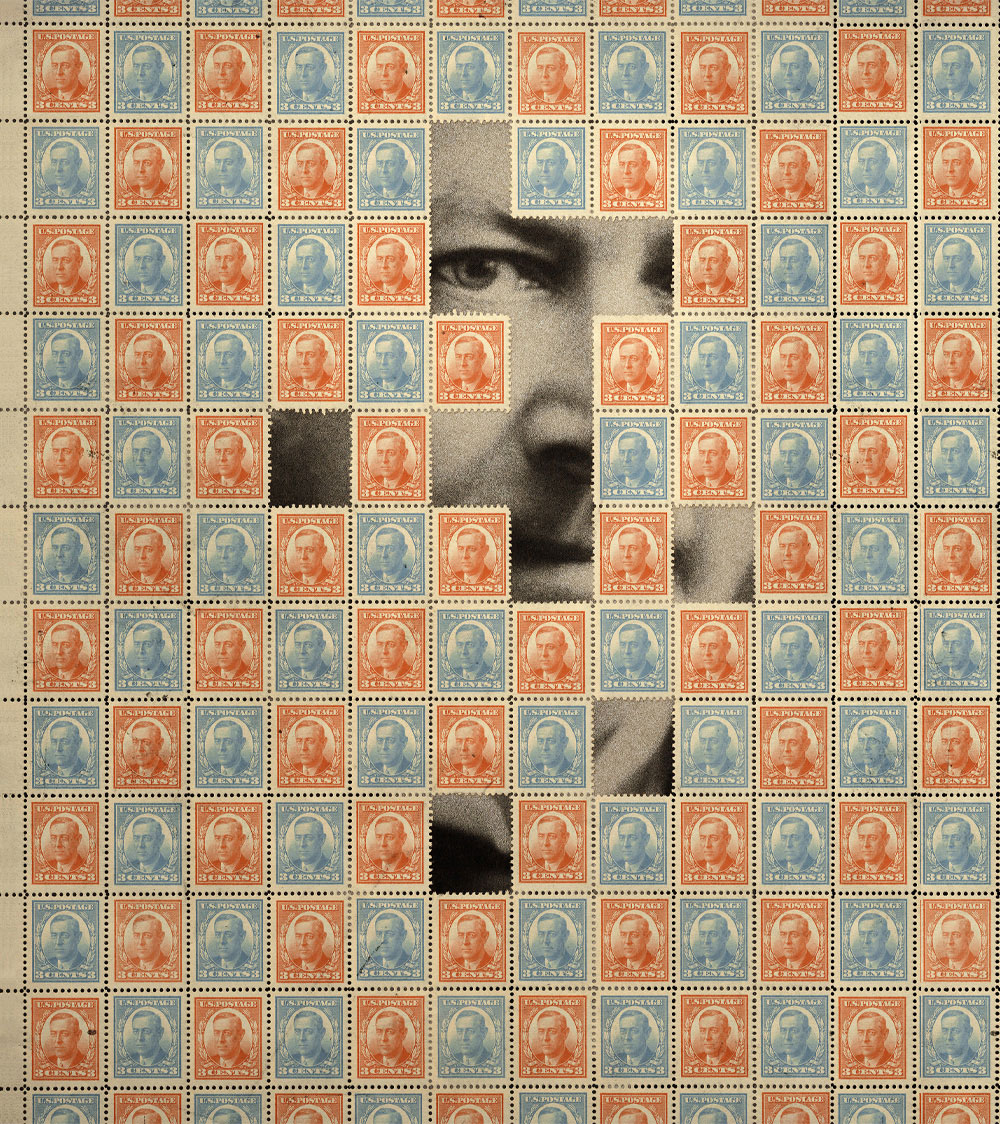

His best-known target was the Masses, a monthly published in New York City. Named for those who socialists were convinced would triumphantly shape history, it was never actually read by the masses—its average circulation hovered around 12,000. But it was one of the liveliest journals the United States has ever seen, publishing a mix of political commentary, fiction, poetry, and narrative reporting, and pioneering the sort of cartoons captioned by a single line of dialogue for which the New Yorker would later become famous. A “slapdash gathering of energy, youth, hope,” the critic Irving Howe later wrote, the Masses was “the rallying center…for almost everything that was then alive and irreverent in American culture.”

The Masses editor Max Eastman had met Woodrow Wilson several times, even visiting him at the White House. But that was no protection now, for there was no doubt where the magazine stood on the war. One cartoon, for example, showed a skeleton rising out of a dark pool while clasping several screaming figures in its arms, with the caption “Come on in, America, the Blood’s Fine!” Another, one that reportedly infuriated Burleson, showed the Liberty Bell crumbling. The postmaster general declared the magazine’s August 1917 issue “unmailable,” and soon afterward revoked its second-class mailing permit entirely. Losing such a permit multiplied a publication’s mailing costs at least eightfold—an expense few could afford.

(This was not the last time an American president would come after a magazine he didn’t like. During Ronald Reagan’s presidency, Mother Jones was forced to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees fighting an ultimately successful battle to prevent the IRS from taking away our tax exemption as a nonprofit organization.)

Furious about the growing repression, Eastman complained that “you can’t even collect your thoughts without getting arrested for unlawful assemblage.” For the government, barring the Masses from the mail was not enough; it soon put Eastman and several others associated with the magazine on trial for violating the Espionage Act—twice, because the first trial resulted in a hung jury. At the second, writer John Reed testified powerfully about reporting from the front line in Flanders, where, in no man’s land, “the wounded had lain out there screaming and dying in the mud.” This carnage had made a soldier start shrieking so uncontrollably that his comrades gagged him, tied his arms, “and took him back to the base hospital.” His eloquence was powerful, and the jurors voted 8–4 for acquittal. But the country’s best magazine was silenced for good.

Before long, Burleson would stifle virtually the entire socialist press, with a prewar combined circulation of some 2 million. Particularly devastated were the many rural socialist papers, which had no other way but the mail to reach their subscribers. Only one in 10 were still publishing by 1920.

Another Burleson target was the nation’s large foreign-language press. After all, many ardent patriots thought, who knew what manner of subversion was being preached right under your nose by the roughly 2,000 newspapers and magazines in dozens of languages, from Slovak to Japanese, which no proper American could read?

A new law soon required that for any article to be published in another language “respecting the Government of the United States, or of any nation engaged in the present war,” the editor had to first file a complete translation with the local postmaster. This was a crippling expense, and also created a backlog of translations awaiting approval. Before any direct censorship even took place, many periodicals were forced to close.

Nevertheless, the government soon decided that requiring translations wasn’t enough, and the Justice and Post Office departments jointly set up a bureau to keep an eye on such publications from the main New York City post office across from Penn Station. This bureau employed more than 30 translators and made recommendations about what to censor. A publication could come under suspicion even, in the words of one functionary, from “tendencies looking toward social equality.” Officials prided themselves on being able to catch sedition in almost any tongue, although they were once flummoxed when they could not find anyone who knew Ladino, the language of Sephardic Jews. Finally the bureau discovered a Ladino speaker at another government agency, who examined the newspaper under suspicion and reported that it “was not an offensive publication.”

As the author of more than a dozen books himself, Wilson knew many writers, and they besieged him with anguished letters protesting censorship. In response to one such plea from writers for the doomed Masses, Wilson forwarded the letter to Burleson with a note saying, “These are very sincere men and I should like to please them.” This was the president’s usual style with his Cabinet. As if still a professor critiquing students’ doctoral theses, he tended to give suggestions rather than orders.

President Woodrow Wilson and his cabinet. Back row: Woodrow Wilson, William G. McAdoo (Secretary of Treasure), Thomas W. Gregory (Attorney General), Josephus Daniels (Secretary of the Navy), David F. Houston (Secretary of Agriculture), William B. Wilson (Secretary of Labor) ; front row : Robert Lansing (Secretary of State), Newton D. Baker (Secretary of War), Albert S. Burleson (Postmaster General), Franklin K. Lane (Secretary of the Interior), William C. Redfield (Secretary of Commerce).

Apic/Getty

Burleson replied that “the publications involved have neither been suppressed nor suspended, but particular issues of them which were unlawful have been refused transmission in the mails, as the law requires.” There were a few more mild complaints from Wilson, but only twice did Burleson bend to the president’s suggestions. On all other occasions, the postmaster general’s axe continued to fall. Not only did Wilson fail to restrain him; neither did the attorney general, Thomas Gregory, a zealous enforcer of the Espionage Act. Burleson and Gregory, another Confederate veteran’s son and a fellow Texan, were fond of angling together for bass in the Potomac.

On at least one occasion, the president urged an even harder crackdown on the press. In September 1917, Wilson sent Gregory a copy of an obscure Chicago antiwar newspaper that had provoked his ire, the People’s Counselor, requesting, “I would very much like you seriously to consider whether publications like the enclosed do not form a sufficient basis for a trial for treason…One conviction would probably scotch a great many snakes.” Gregory saw to it that the paper’s publisher was arrested and indicted under the Espionage Act.

Along with outright censorship came what emerges under all such regimes, self-censorship. The editor of New York’s Jewish Daily Forward, the country’s leading Yiddish newspaper, announced in the fall of 1917 that “the paper will henceforth publish war news without comment and will not criticize the allies, in order to avoid suspension of mailing privileges.” Many other editors quietly made similar decisions.

Before long, the post office would ask the “cooperation of librarians in the matter of destroying all copies in their libraries, of books that have been declared unmailable.” Nor was it the only arm of the government to move beyond its jurisdiction. The War Department gave the American Library Association a list of books it wanted removed from library shelves. After a novel called Men in War by a Hungarian pacifist was banned from the mail on the grounds that it called the ongoing conflict a “wholesale cripple-and-corpse factory,” the Army’s Military Intelligence branch kept its publisher, Boni & Liveright, under surveillance to see if it was preparing to publish anything similar.

Once Burleson killed off the Masses, Max Eastman and his sister, Crystal, a journalist and feminist militant, started a new magazine, the Liberator, with many of the same writers. They steered a more careful course and avoided being shut down. But the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation often wreaked havoc on the magazine’s distribution. If Emma Little of 1430 Kern St., Fresno, California, wondered what had happened to one package of Liberator issues she evidently planned to sell or distribute, Justice Department files reveal that Special Agent George Hudson had seized them from the Wells Fargo Express company because they “contained seditious matter.”

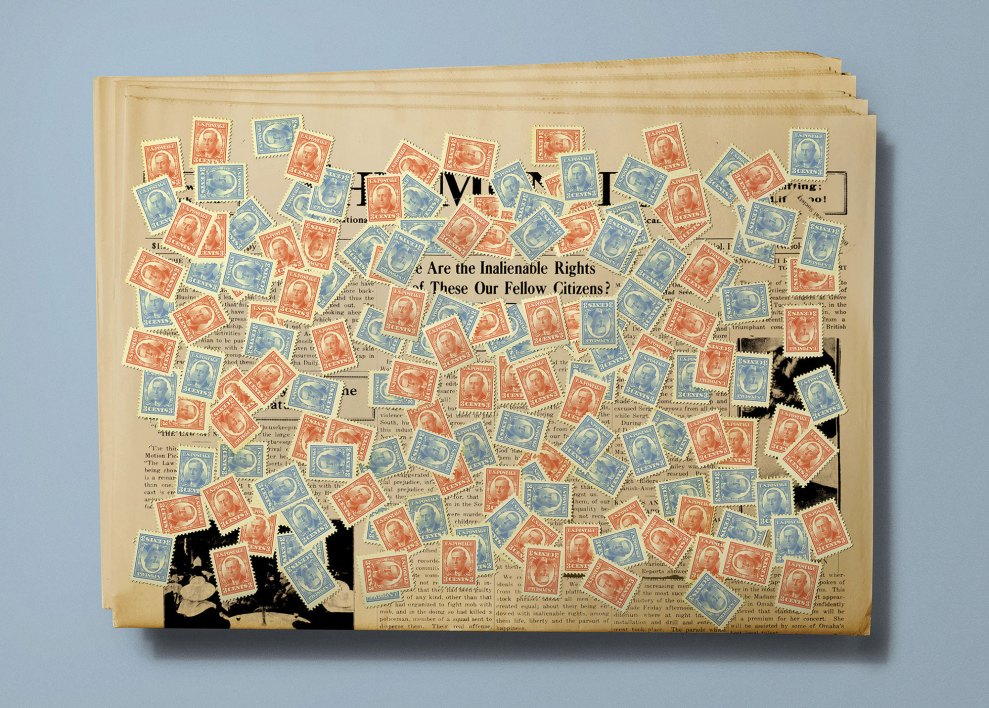

Less than a year after the passage of the Espionage Act, The Cardinal had deemed 44 American periodicals entirely “unmailable,” a total that would, before long, include some 30 more. He also banned specific issues of many more or warned publishers he would do so if they didn’t fall in line. The Nation earned his wrath for criticizing a labor leader who was a key Wilson ally; the Public, a progressive Chicago weekly, for urging that the government raise funding for the war by taxes instead of loans, to put more of the burden on the wealthy; and the Black-led Amsterdam News when it complained that Black soldiers were dying for the rights of Serbs and Poles in Europe while they risked being lynched at home.

Burleson banned issues of the Gaelic American for backing Irish independence and of the Freeman’s Journal and Catholic Register for reminding readers that Thomas Jefferson had also supported that cause. Following his lead, local postmasters around the country began removing from the mail newspapers and magazines they didn’t approve of. Southern postmasters were particularly likely to do this when Black periodicals like the Chicago Defender or W.E.B. Du Bois’ the Crisis published exposés of lynching.

Sometimes, after banning an issue or two, the postmaster general would declare that, because a periodical had not been publishing regularly, it was no longer entitled to second-class mailing privileges. Burleson also seized 600 copies of a pamphlet, “Why Freedom Matters,” not because it criticized the war—it hadn’t—but because it attacked censorship. He found “unmailable” no fewer than 14 pamphlets published by the National Civil Liberties Bureau, soon to become the American Civil Liberties Union.

From such a ban, there was no appeal. The prohibited publications could only file lawsuits—none of which, during Burleson’s tenure, succeeded. Sometimes, as if anticipating the hero of Kafka’s The Trial, a journalist could not even learn what he or she was accused of. According to Oswald Garrison Villard, the editor of the New York Evening Post, William H. Lamar, the post office’s chief legal officer, once said, “You know I am not working in the dark on this censorship thing. I know exactly what I am after. I am after three things and only three things—pro-Germanism, pacifism, and ‘high-browism.’”

For individual journalists, censorship could be the least of their worries. When the San Antonio Inquirer, a Black newspaper in Texas, published a letter that the Justice Department thought too favorable to some Black soldiers who had mutinied, the paper’s editor was sentenced to two years in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. At least 25 other journalists were among the more than 400 men and women who spent a year or longer in federal prisons between 1917 and 1921 solely because of something they wrote or said, according to a tabulation by lawyer and historian Stephen M. Kohn. “The number of political dissidents who served less than a year in prison,” he cautions in his book American Political Prisoners, “is simply too great to document.”

In 1918, Congress passed the Sedition Act, in effect a set of amendments toughening the Espionage Act. The new law made it criminal to provide “disloyal advice” about buying war bonds, or to “utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States.” The Sedition Act also made legal something Burleson had already been doing with great zest: refusing to deliver mail. A committee preparing the defense of hundreds of arrested members of the Industrial Workers of the World, the country’s most militant labor union, as well as trying to support their wives and children, found that checks mailed to it never arrived. Letters to possible witnesses were never delivered. The staff of a socialist paper in Milwaukee failed to receive business correspondence or even their subscriptions to the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune. And, having already bottled up most Socialist Party publications, the post office now stopped delivering letters between the party’s Chicago headquarters and some local chapters. This was a crippling blow at a time when the only other means of communication were costly telegrams or long-distance phone calls.

Censorship spread to education. Columbia University’s war-hawk president, Nicholas Murray Butler, had two pacifist faculty members fired. New York state passed a series of laws affecting schoolteachers: They could now lose their jobs for “treasonable or seditious statements”; they had to be American citizens; and all schools had to teach a course in patriotism and citizenship. New York City went further, requiring all teachers to sign loyalty oaths, and holding hearings where students testified about what their teachers said in class. Across the country, teachers and professors lost their jobs.

The work the government had started was continued by mobs. When E.A. Schimmel, a professor of modern languages at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, antagonized a local vigilante group, the Knights of Liberty, its members tarred and feathered him. An Iowa minister and a friend were dragged through the streets with ropes around their necks until one of them agreed to buy a $1,000 war bond. In Berkeley, California, a mob of thousands, including many university students, attacked a pacifist church, setting fire to its tent tabernacle and several wooden cottages surrounding it, while tossing the pastor and two elders into the church’s baptismal tank. In Madison, South Dakota, a crowd of hundreds surrounded the family home of 30-year-old Ingmar Iverson, the state chair of the Socialist Party and a conscientious objector. When he failed to appear, members of the mob chopped their way through his roof with axes, tied his hands and feet, and prepared to paint him yellow. Police rescued him just in time, but the mob dispersed only when Iverson promised to leave town.

When the first World War ended with the armistice of November 11, 1918, there was no letup in repression. Burleson continued to block the left-wing newspapers and magazines he despised. The postmaster general, the New York World commented, “appears to think that the war is either just beginning or is still going on.” When a US District Court found in favor of several publications that had challenged him, Burleson, with Wilson’s full approval, appealed the verdict. Nor did Congress have much interest in ending censorship. A proposal by a few senators to do so was quickly doomed. Robert La Follette, the strongest progressive voice in the Senate, declared that its failure “ought to make the framers of the Constitution open their eyes in their coffins.”

One ongoing Burleson target was the nation’s leading socialist daily, the New York Call, which fought for two years to get its second-class privileges restored. But Burleson ruled that, because the Call had violated the Espionage Act, it was not a bona fide newspaper and so was not entitled to second-class privileges. This was as if, the New Republic noted, the Pennsylvania Railroad refused to sell a ticket to someone convicted under that law “on the ground that…he was no longer a ‘person.’”

The Justice Department’s patriotic venom also persisted. In November 1919, a year after the armistice, three men in Syracuse, New York, published a pamphlet calling for amnesty for conscientious objectors still behind bars, complete with drawings of the well-documented, notoriously brutal treatment these pacifists had received there. The leaflet’s authors were arrested, indicted under the Espionage Act, and sentenced to 18 months in prison.

Albert Sidney Burleson remained in office until the last day of the Wilson administration, March 4, 1921. He then retired to Texas, until his death in 1937. Wilson’s successor, Warren Harding, a former newspaper publisher, had—for all his flaws—no desire to continue censorship. His postmaster general limited himself to the usual distribution of patronage jobs and peripheral involvement in one of the administration’s several corruption scandals. But dozens of the periodicals Burleson had killed off between 1917 and 1921 never came back to life.

Today, news and opinion come to us in many forms beyond type on a printed page. And just as technology has mushroomed, so have the threats to freedom of speech. Every week, it seems, brings new restrictions, from Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill and the banning of dozens of math textbooks to prohibitions on teaching anything related to critical race theory and the removal of classic children’s books, like Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen, from a public library in Texas. In recent months, at least 11 states have passed laws regulating the teaching of history, and right-wing activists in at least five have forced school libraries to remove particular books from their shelves. With such pressure only mounting, the censorship and repression of a century ago stand as a reminder of how fragile the civil liberties we take for granted can be, and how urgent their defense.

Adapted from Adam Hochschild’s American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, was just published by Mariner Books.