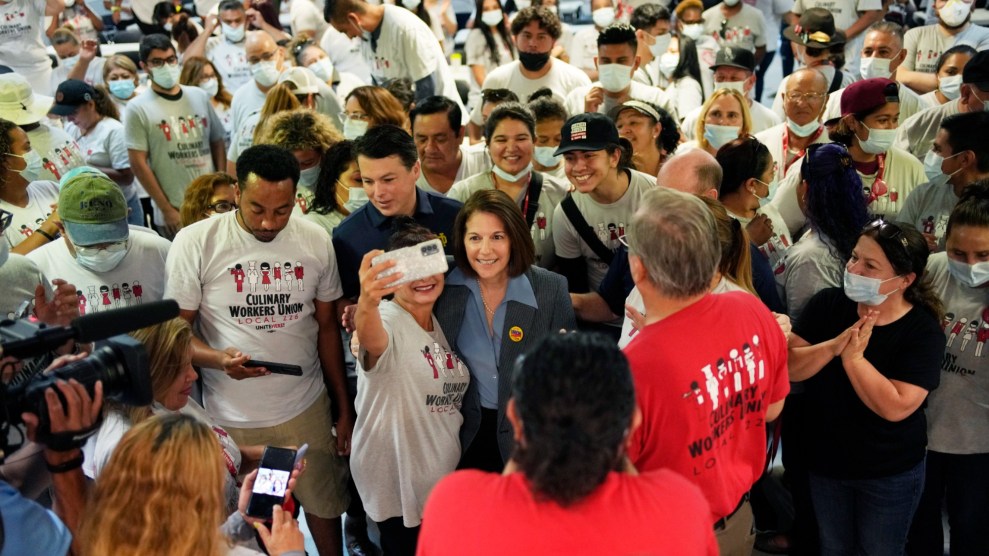

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto meets with members of the Culinary union.John Locher/AP

For the past two months, Irving Zavaleta, 36, has been staying at an Airbnb in the central area of east Las Vegas, but he hardly spends any time there. Instead, for 14 hours a day, every day, he is most likely to be found at Mi Familia Vota, a national nonprofit promoting voter participation among Latinos. Zavaleta is a program manager at their local headquarters about a 10-minute drive from his temporary lodging. “I’m staying close by since I pretty much live in the office,” he tells me.

Zavaleta spearheads a voter mobilization effort that focuses on people known as “low to mid-propensity voters,” which is to say those who are most likely not to vote because they haven’t voted regularly in the past or have never voted at all. The people Zavaleta reaches out to include newly naturalized immigrants and young Latinos who recently turned 18 and became eligible to vote.

Zavaleta and his “small but mighty” team of 15 to 20 people on any given day, have been emphasizing the most pressing issues on the ballot this election—democracy, LGBTQ and immigrant rights, abortion—while also resorting to what he describes as “social pressure.” The idea is to impress on prospective first-time voters the potentially decisive nature of their participation. Their future and that of their families are in their hands—an empowering message that organizers hope will translate into action. “We’ll tell them: Latinos can make a difference this November,” he says. “We can decide who our next governor or senator will be. We can make the decision here in Nevada.”

He’s usually based in North Carolina, but since September as Election Day approached, he decided that Nevada was the obvious place to be. This swing state is one of the epicenters of the battle for control of the narrowly divided US Senate and includes some of the most competitive House races in the country. It is also where Latino voters are expected to have an outsized influence on the outcome of the elections. “The stakes are high,” Zavaleta, who was born in Veracruz, Mexico, says, noting that projections by the nonpartisan National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials Educational Fund show that more than 165,000 Latinos in Nevada will be casting ballots in November and they will comprise more than 1 in 5 midterm voters in the state. “That is huge.”

A lot is at stake in the Nevada US senate race. @CortezMasto @AdamLaxalt #NVpol https://t.co/HvbntsyrL4

— Irving Zavaleta (@irvinghzavaleta) November 1, 2022

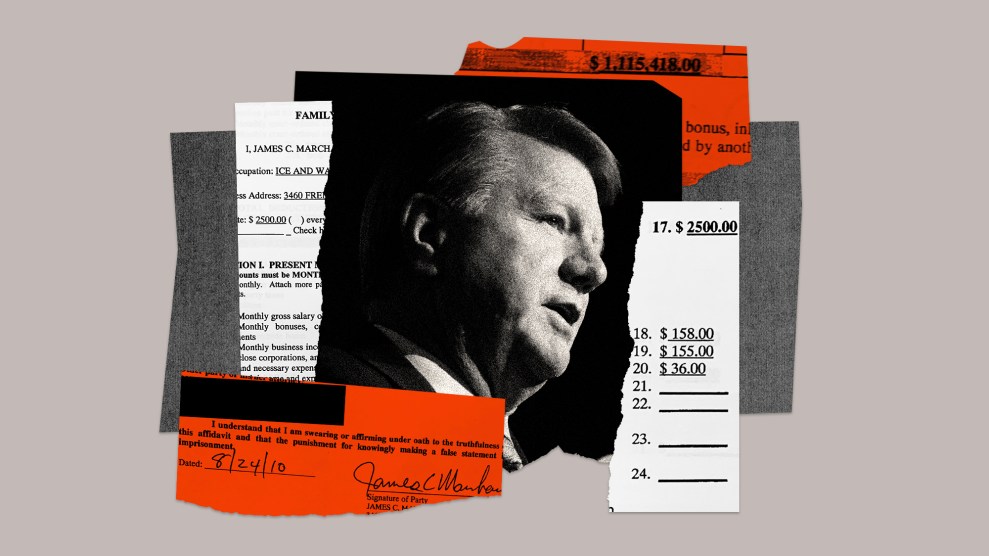

Perhaps in no other race is securing Latino voters turnout as critical as in the neck-and-neck contest that could oust Democratic incumbent and first-ever Latina Senator Catherine Cortez Masto, and determine the balance of the chamber. She is facing off against Republican Adam Laxalt, a former state attorney general, Trump loyalist, and election denier. Both candidates have been targeting working-class voters hit hard by the pandemic with speeches focused on economic anxiety and the high cost of living.

Cortez Masto’s campaign also hopes to turn voters away from her opponent by attacking his anti-immigrant and anti-abortion stances. He believes decisions on abortion access should be left to the states and wrote in an op-ed for the Reno Gazette Journal aimed at “setting the record straight” on his views about the issue. He noted that he would support a referendum restricting the proceeding after 13 weeks of pregnancy. Meanwhile, following the GOP playbook in races across the country, Laxalt has tried to associate the Democratic candidate with socialism, soaring crime, and a border crisis. But despite Laxalt’s concerted efforts to woo Nevada’s Latino voters and with polls suggesting Cortez Masto’s might stand more favorably with them, what could ultimately tip the scale on this election is success in the get-out-the-vote push.

“We’ve known early on that race was never about Laxalt and Cortez Masto,” says Emmanuelle Leal-Santillan, national communications director of the Latino-led voter mobilization group Somos Votantes, whose affiliated PAC has invested heavily in English and Spanish-language ads supporting the incumbent and encouraging voter registration. “The election is between [people] coming out to vote for the Senadora and Democrats and not voting…This has always been a turnout election in our view.”

Somos Votantes has been sending 200 canvassers a day to knock on doors and talk to voters across Nevada and Arizona, according to executive director Melissa Morales. The group also has specific outreach initiatives aimed at Latino women and young people who Morales says lean heavily Democrat but lag in voter turnout. Their messaging strategy has been to acknowledge people’s economic pain and propose positive solutions “rather than playing a rhetoric or a blame game.”

“I don’t think we’re going to see a lot of Latino Democrats shift to Republicans,” Morales adds. “I’m more concerned about whether Latino Democrats stay home.”

Yesterday was a historic day! My mom became a citizen on September 8th & this is her first time voting.

Vote for people who can’t vote, vote for your children & vote for their future—because they are the change we need as a country.

Mom, this is your day, & I'm so proud of you. pic.twitter.com/FnZn9XNszp

— Steven Horsford (@StevenHorsford) October 31, 2022

While the economy, health care, and jobs are top of mind for voters, immigration policy also carries some weight, particularly in the contested Nevada gubernatorial race. Incumbent Democrat Steve Sisolak could be unseated by GOP challenger and Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo, who has bragged about deporting 10,000 people. In an attempt to dissuade GOP hardline voters from supporting Lombardo, the powerful Culinary Workers Union, which counts many immigrants as members, recently sent out mailers stating that they once endorsed the candidate and that he was softer on immigration than he claims. Immigration might not be the top motivator for turnout to vote, but it can certainly be a disqualifier for supporting some candidates. “It’s very personal and local to Latinos and families in Nevada,” Morales says. “The unfortunate and sad thing about an issue like immigration is that so much of the community that is affected by it is unable to vote.”

On the first day of early voting in Nevada on October 22, Somos Votantes organized an event outside the East Las Vegas Library where community members cheered on about 10 first-time voters as they cast their ballots accompanied by the tunes of a mariachi band. Jacinto Alfaro-Martinez stood among them. He turned 18 in June and voted for the first time last month after having done volunteer work around voting education for two years.

“This election is personal to me,” says Alfaro-Martinez, whose parents are non-naturalized immigrants born in El Salvador and Mexico. “There’s more than just myself that I’m voting for. I’m voting for the people who can’t vote, for my mom, my dad.” He was part of Somos Votantes’ youth leadership program and has since become a staff organizer. Whether he’s handing out flyers, doing phone banking, or attending community events, Alfaro-Martinez says there’s a “strong sentiment towards voting and making change.” Of Sen. Cortez Masto, he says, “She cares about people like me.”

Devonte is a 1st time voter who knows hardworking Latinos need to show up for each other at the ballot box. When he casts his vote for La Senadora Cortez Masto, he's voting for good-paying jobs, affordable health care and low-cost childcare, which affect our comunidad every day pic.twitter.com/VjgUfiUGtm

— Somos Votantes (@SomosVotantes) November 2, 2022

Caridad Abejean, 56, is one of the thousands of newly naturalized immigrants who have become eligible to vote in Nevada in recent years. Between 2016 and 2020, almost 43,000 immigrants have gone through the citizenship process in the state, according to a “New American Voters 2022: Harnessing the Power of Naturalized Citizens” report. That’s a larger number than the margin of roughly 33,000 votes by which President Joe Biden carried Nevada two years ago. Abejean, who is originally from Cuba and went through the Culinary Workers Union citizenship project, which has helped 18,000 people become citizens since 2001, cast a ballot for the first time this year. She is one of the 450 canvassers the Culinary Workers Union has sent to Reno and Las Vegas who have already knocked on 950,000 doors. “I’m a very proud first-time voter,” Abejean told me in Spanish. “I’m happy knowing I’m giving a voice to our community. I’m doing this with my heart.” Her vote, she says, will go towards protecting women’s rights to choose and “decide over our own bodies.”

In this final stretch, it’s all hands on deck to get voters to the ballots until the last vote is cast. For Make the Road Action Nevada, a nonprofit focused on engaging Latinos in the political process, engagement with first-time voters, including those who only speak Spanish, is a priority. Audrey Peral, the organization’s director of organizing, recalls how during a recent voter registration training session they were able to register a young man who had come in with his father to volunteer, and whose 18th birthday was just a few days away. (In Nevada, 17-year-olds can preregister to vote and automatically become eligible to vote upon turning 18.) Not only has he voted for the first time, but he’s also joined the organization’s paid canvassing program.

“What we focus on is the empowerment piece and the informational component,” Peral says, adding that this is a year-round effort, not just before the elections. “Making sure folks understand what is at stake…We’ve found that when we take time to explain how [voting] impacts their daily lives, they very much do care about the issues. These are everyday people who are dealing with real problems and helping them understand they have the power to change that is important.”

For his part, Zavaleta has been using the little free time he has to do phone banking. Because of Nevada’s transient population and shifting demographics, “We always have to be educating, engaging, and encouraging people to get to the polls. It never stops.”