Mother Jones; Stu Moffat/Unsplash

The day after the Brazilian national team beat Switzerland in the group stage of this year’s World Cup, a handful of players went out for dinner. The group included Arsenal’s Gabriel de Jesus and Real Madrid’s Vinícius Júnior. Ronaldo, Brazil’s former striker and a talismanic figure in football, attended. They chose to eat at Nusr-Et. That was a mistake.

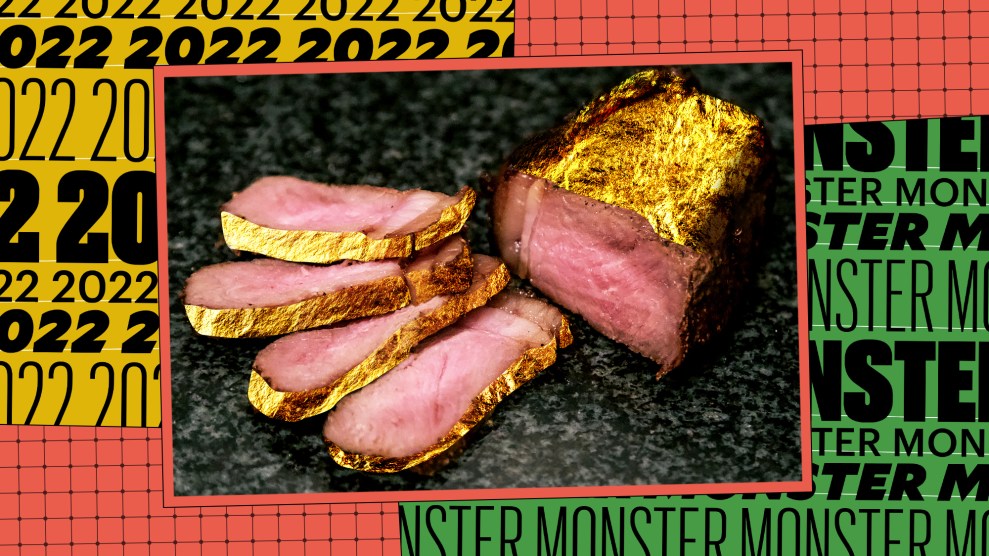

A restaurant tucked in a five-star Sheraton hotel in Doha, Qatar, it is part of a chain of steakhouses run by Turkish-born Chef Nusret Gökçe. You likely know Gökçe as Salt Bae. He rose to fame in 2017 after a viral social media video turned his over-the-top signature move—sprinkling salt on meat with an arm scrunched into his torso—into a meme. Since then, he has become an odd restauranter. Across the world, he has opened (seemingly average) places to buy steaks for ridiculous prices. His trick is an aura of luxury. In particular, he has become famous for his gilded steaks. At the restaurant, a piece of rib eye coated in 24k gold leaves goes for $2,310.

I would be willing to forgive the frivolous display of opulence if it weren’t so tacky. Or if Brazil, playing with a B-team, hadn’t lost their next match that week to Cameroon—ending a streak of 17 straight group games without a loss in World Cups. Or if, after all of this, they had won the World Cup, instead of crashing out to Croatia on penalties despite having one of the most talented squads. But, because we lost, my anger has not been sportswashed.

I won’t dispute that these players should be allowed to do whatever they want with the preposterous amount of money they make. But that doesn’t take away from the fact that what they chose to do signals how disconnected they have become from the reality of the people cheering for them. The spectacle didn’t sit well with Brazilians. Many promptly noted online how distasteful it was in light of Brazil’s flagrant wealth gap and worsening food insecurity. (Some Twitter users remarked on the hypocrisy that one of the players, wearing a watch worth more than $500,000, has been involved in a legal dispute over child support.)

Father Julio Lancellotti, a popular Catholic priest who works with unhoused people in São Paulo, described the affair as outrageous and said “it is scandalous in a country where 33 million people live in hunger, in a world where millions of people starve and die from malnutrition and in a country like Qatar, where there is immense poverty and great inequality.”

That detachment—not surprising considering that only three of the selected 26 footballers currently play in Brazil—could not have been better captured than by a moronic statement from Ronaldo. During a podcast interview, he suggested the lavish dinner could perhaps inspire the less fortunate to work hard and succeed. Because nothing screams meritocracy and social justice more than a piece of gold-plated steak that is probably not any better than the good quality meat Brazil has in abundance.

It is undeniable that football has been an important instrument of social and economic mobility and it has shaped Brazil’s cultural identity domestically and abroad in more ways than one. But it’s also true that this modern oligarch-dominated, marketplace-oriented version of the sport appears closer to the elitist origins of its rooting in late-19th century Brazil than to any ideal of a great equalizing force.

After I went on a long rant about this on a chat with my family, my father offered that I might be missing the whole picture in my indignation toward the “misstep.” The players, he said, are embedded in a toxic environment and measure and display their value—as sportsmen, as people—based on how much they earn and spend. (The attraction to Salt Bae’s restaurant goes far beyond just Brazilian players.) Many of them go from a life “in the favela to Mount Olympus without any editing in between.”

Still, not all Brazilian players have demonstrated a lack of class consciousness and leadership outside the field. At 25, Richarlison—who scored two strong contenders for best goal of the contest—stands out from the bunch.

The Tottenham forward has been vocal in his support for racial justice protests, including after the murder of George Floyd. He joined vaccination campaigns during the pandemic and acted as an ambassador for scientific research institutes. He denounced fires in the Pantanal wetlands. “I’ve been through a lot of in my life,” he has said when explaining his involvement with social issues. “I think it’s just a matter of putting yourself in the shoes of someone who is going through a difficult time, having empathy.”

As a Brazilian and football fan, I can say Richarlison makes it more palatable to cheer for this team. But the gold steak will be one more aspect about this World Cup that leaves a bad taste in the mouth.

As usual, the staff of Mother Jones is rounding up the heroes and monsters of the past year. Find all of 2022’s here.