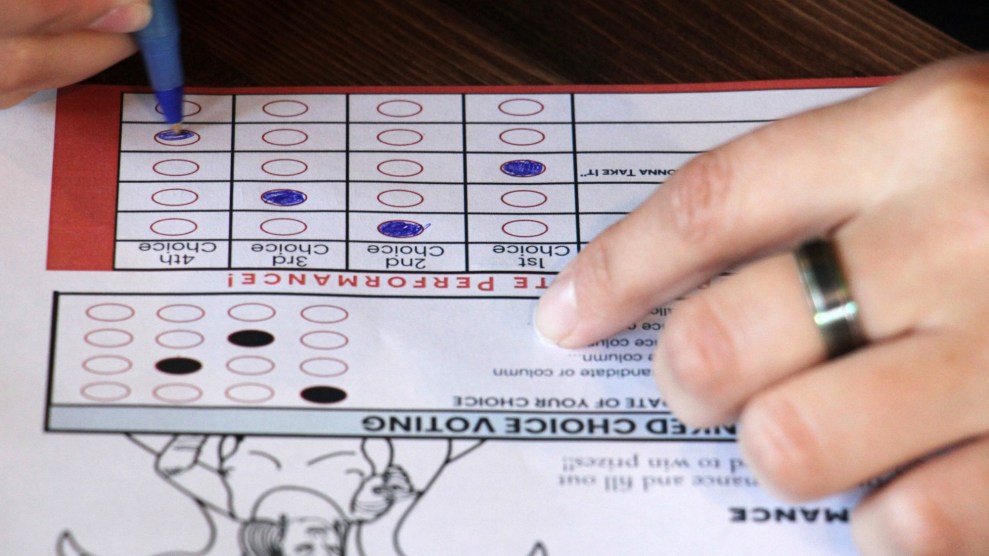

Alaskans learn about ranked choice voting in a mock election for drag queens. Mark Thiessen/ AP

It’s the system to “save America,” to some experts. To Arkansas Republican Sen. Tom Cotton, it’s a “scam.” The ever-so-eloquent wordsmith Donald Trump called it “crap voting” and a “total rigged deal.” Its backers see it as a path back to political diversity. So do its opponents. None of them are right. It’s ranked-choice voting, Alaska-style.

In November, Alaska’s high-profile House and Senate races pitted Trump backers against moderates, a test of the state’s famous independent streak. That quickly made Alaska the most prominent state to use ranked-choice voting, which it debuted in that election. The system, which redistributes a losing candidate’s votes to their supporters’ second choices, is increasingly hyped as an anti-extremism silver bullet. Alaska, where ranked-choice helped take down the MAGA crowd, is a key part of that. But it’s just one of three states, two counties, and at least 58 municipalities that use it—from Maine, which enacted RCV in 2016, to Nevada and six cities, including Seattle and Portland, that just voted to adopt it.

But it’s Alaska, where no Democrat has held major office since 2008, that’s driving ranked-choice voting’s new reputation as a “surprisingly simple tinker that could fix our democracy.” The state’s MAGA candidates, boosted by Trump’s two-for-two record there, were poised to do well in November. But Rep. Mary Peltola broke that streak in Alaska’s House, beating celebrity ex-governor Sarah Palin with help from ranked-choice. In the Senate, “disloyal and very bad” Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski—unlike other Republicans who stood up to Trump—was spared a certain primary takedown by his handpicked candidate. That’s entirely thanks to Alaska’s new system.

Peltola “is kind of a poster child” for what ranked-choice voting can do, says Rob Richie, the president of FairVote, a nonpartisan advocacy group that backs ranked-choice. Peltola, a former state legislator, picked up enough second- and third-choice votes to flip Congress’ longest-standing GOP seat in an August special election, despite initially lacking the funding of her conservative competitors.

RCV’s advocates say that it creates a healthier political culture, with more opportunity to pick a candidate voters actually like, rather than the lesser of two evils. They also argue that ranked-choice disfavors extremists’ go-to strategy of rallying their base to flood low-turnout primaries. But transforming political culture and checking extremism are huge undertakings, and ultimately, Richie says, “RCV is just a ballot type.” It won’t unleash a bunch of nonexistent moderates, favor an ideology, or reduce the actual number of extremists. It’s a modest way to better empower the electorate, with growing bipartisan support. The problem: Republicans are banning it anyway.

In February, Tennessee Republicans outlawed ranked-choice voting because officials in Shelby County, home to Memphis, talked about reviving a 2008 RCV law that was signed but never implemented. In March, Florida Republicans passed another ban on ranked-choice as a little-noticed part of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ widely criticized election bill, media coverage of which focused on its new state force of “election police” to investigate supposed voter fraud.

Palin blamed the system for her back-to-back losses in the special election and midterms, despite the fact that she is wildly unpopular in Alaska. She’s repeatedly called ranked-choice “un-American,” and signed a petition to put it to another statewide vote, although the Alaska Supreme Court has already upheld RCV in the face of challenges. In any case, the system has actually benefited Alaska Republicans, who narrowly took the state House after second-choice votes helped two Republicans pull ahead.

But there are other avenues for ballot reform: Alaska also switched to nonpartisan primaries, which Nevada has now adopted as well. Like RCV, nonpartisan primaries are a tweak—they’re not the escape from party “tyranny” sought by backers like food magnate and “rational centrist” Katherine Gehl, a major force behind Nevada’s RCV drive.

“If the hope is that there are going to be more moderate candidates,” says Dan Lee, a political scientist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, “the problem is that there isn’t clear evidence that they have that effect.” Alaska may have elected some moderates, but that’s a minuscule sample—and the most extreme candidates still made it to the general. (Maine, also famously independent-minded, uses RCV but maintains party primaries.)

In a nonpartisan system, there’s no guarantee that the major parties will make it to the final ballot. That was a fear for Democrats in the days before the Alaska primary: Peltola, finishing fourth, barely advanced to a general election that would otherwise have included just Republicans and an independent. And not everyone thinks disempowering political parties should be the goal. “Anti-party reform doesn’t rest on a coherent theory of politics,” says Jack Santucci, a political scientist at Drexel University in Philadelphia. “A coherent theory begins with the observation that politics is about choosing sides.”

Both Lee and Santucci emphasize the importance of other reforms. Santucci suggests, among other things, multi-seat Congressional districts. Lee believes that a true open system, in which independents or third-party voters could vote in an establishment party’s primaries, would be a step in the right direction. “I don’t think RCV needs to be a single thing,” says Richie, the FairVote head. “It’s a better ballot type. Making sure votes count is the common thread.”

The GOP, and its desperate measures to block those changes, face a problem: the will of the electorate. Ranked-choice voting has growing bipartisan support, as November’s elections proved. So does ballot reform in general. The MAGA politicians banning it? Not so much.