Modern conservatives love to own the libs by supporting people who claim they’ve been “canceled.” Yet Kyle Rittenhouse can’t seem to draw a crowd, no matter how many times he gets shut down.

In January, Rittenhouse headlined the Rally Against Censorship in Conroe, Texas, an event you’d expect to draw a healthy turnout in a Texas county that voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump in the 2020 election. But when I arrived, only about six people had lined up for the early-access VIP snaps with Rittenhouse, mostly paunchy older white men in black button-down shirts, black jeans, and cowboy hats.

In 2020, Rittenhouse, then 17, shot three people, killing two of them, during protests over police violence in Kenosha, Wisconsin. He became a household name. Prosecutors charged him with multiple felonies. During his trial, Rittenhouse testified that he’d acted in self-defense. The jury acquitted him of all charges in November 2021.

At first, Rittenhouse espoused a hope for a new life. Four days after his not-guilty verdict, he told NewsNation’s Ashleigh Banfield that he was considering changing his name, growing a beard, and losing some weight so people wouldn’t recognize him in public. “I just want to be a normal 18-year-old college student trying to better my future and get into a career in nursing,” he said, explaining that he didn’t like fans asking him for selfies. “I just don’t want to be taking pictures with people I don’t know.”

Yet there he was in Conroe, more than a year later, sporting not a beard but a suit and tie and mugging for photos with strangers who’d paid the $275 VIP fee to meet him. Rather than slink off into anonymity after his acquittal, Rittenhouse has spent the past year trying to rebrand himself as a free speech and gun-rights activist. Following the siren song of the right-wing industrial complex, Rittenhouse, now 20, spends his time going on podcasts, attending conventions, and taking selfies with fans. He tends to stick to safe spaces: Zoom interviews from his bedroom with sympathetic B-list right-wing media—Sebastian Gorka, fringy YouTubers—or the occasional star turn at scripted conventions hosted by the conservative youth group Turning Point USA. He risks few public appearances outside that cozy bubble.

The Rally Against Censorship—sponsored by Defiance Press, a publishing house that has put out books by controversial figures such as noted Islamaphobe Frank Gaffney and infamous Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio—should have been a hot ticket. Indeed, at least 1,000 people had registered for the event online. But as the night wore on, fewer than half of the 450 white chairs I counted ever filled up, even though general admission was free. The empty seats were a stark indicator that Rittenhouse’s quest for conservative influencer status isn’t winning many converts, even as it’s destroying whatever second chance his acquittal might have promised for a normal life.

Defiance had originally planned to host the rally at the local Southern Star brewery. When word spread on social media that Rittenhouse would be there, the brewery pulled out, prompting a wave of furor among conservatives and a barrage of death threats against the brewery owners. A week after the brewery cancellation, Rittenhouse was in Las Vegas during the Shot Show, the gun industry’s biggest trade show. He was scheduled to headline a private event sponsored by the National Association for Gun Rights at a Venetian hotel restaurant. But the hotel, located only two miles down the Strip from where a gunman slaughtered 60 people in 2017, pulled the plug on the event at the last minute, saying that it “did not align with our property’s core event guidelines.”

You guys aren’t going to wanna miss out on this one! @NatlGunRights @dudleywbrown pic.twitter.com/dgQSQGsW3B

— Kyle Rittenhouse (@ThisIsKyleR) January 16, 2023

In an editorial in the Washington Times, Rittenhouse complained that he’d been “stripped of my right of expression at establishments in Texas and Las Vegas” by “far-left trolls.” Not to worry, however, Rittenhouse declared that he would never give up. “I’m sure left-wingers will continue to try to pressure venues to cancel my events,” he wrote. “I’m not deterred. I’m used to firing back.”

When Rittenhouse traveled to Kenosha from his home in Antioch, Illinois, in August 2020 and patrolled the streets with an AR-15 style assault weapon strapped to his chest, the city was on fire. Over that fateful summer of Covid lockdowns, the whole country was awash in protests in response to the police killing of George Floyd in Minnesota. Armed militia groups often materialized to greet the protesters, claiming they were there to “assist” local law enforcement in keeping the peace—so-called assistance that many local police departments tacitly sanctioned.

In Kenosha, the police shooting of a Black man named Jacob Blake had sent protesters streaming into the streets. Cars were torched, buildings burned. Right-wing media fanned the flames with endless footage of the smoldering city and mostly Black protesters. “Joe Biden’s voters really are a threat to you and your family,” Tucker Carlson said during a Fox News segment. “Nobody stopped them from burning down [a] business or burning down the city…The Democratic Party of Kenosha decided to embrace the mob.”

On Facebook, a newly formed militia group called the Kenosha Guard issued a call for “patriots willing to take up arms and defend our City tonight against the evil thugs” to come to the city. Alex Jones’ conspiracy theory website InfoWars amplified the request. Some 4,000 people responded to the Facebook post, some with ominous responses: “Counter protest? Nah. I fully plan to kill looters and rioters tonight. I have my suppressor on my AR, these fools won’t even know what hit them,” one warned. “It’s about time. Now it’s time to switch to real bullets and put a stop to these impetuous children rioting,” wrote another. Groups like the Boogaloo Bois, a far-right anti-government extremist group sometimes associated with white nationalists, flocked to Kenosha.

Into all this chaos walked Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year-old high school dropout pretending to be an EMT, toting a Smith & Wesson assault rifle. He crossed paths with Joseph Rosenbaum, a suicidal convicted sex offender who just hours earlier had been released from a Milwaukee mental hospital. Rosenbaum had been raging, setting fire to a dumpster, tipping over a porta-potty, and screaming threats at random people. Rosenbaum chased Rittenhouse. He was carrying a plastic bag with a toothbrush in it, which he threw at Rittenhouse. A reporter from the Daily Caller who filmed the episode later testified that Rosenbaum lunged for Rittenhouse’s gun, at which point he shot him four times and ran away.

Others in the crowd gave chase, believing Rittenhouse was an active shooter. A protester tripped him, and he landed on the pavement. Another protester, Anthony Huber whacked him with a skateboard and tried to grab his weapon. Rittenhouse shot Huber in the chest, killing him. Another onlooker, Gaige Grosskreutz, ran to the scene. Armed with a Glock pistol, he pointed the gun at Rittenhouse, at which point Rittenhouse shot Grosskreutz, too, shearing off most of his biceps.

With his gun still strapped across his chest, Rittenhouse tried to surrender to the many police officers on the scene. They responded by pepper spraying him and telling him to get out of the way, believing that the real shooter was elsewhere. He went home. His mother later drove him to the police station to surrender.

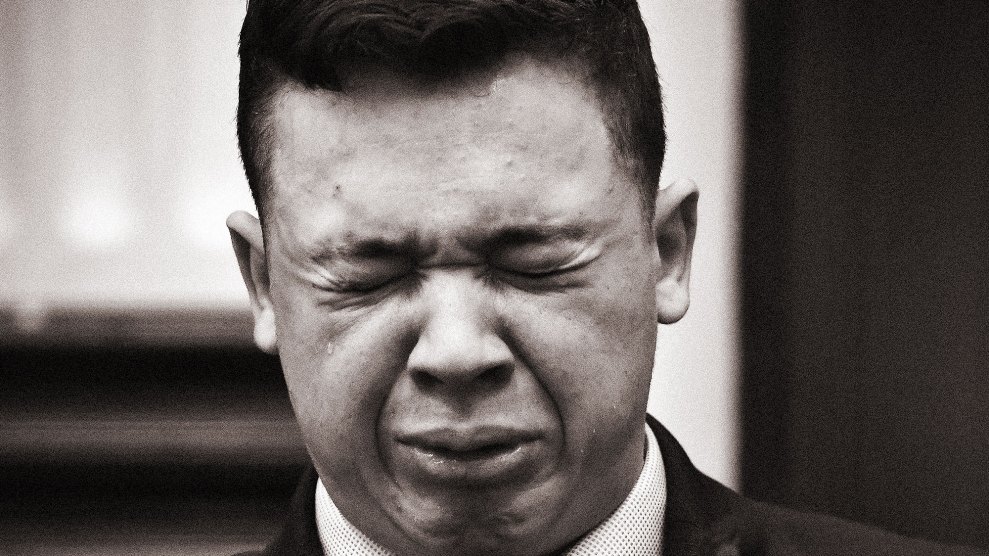

The story went viral. Liberals saw Rittenhouse as a racist vigilante who killed people protesting police violence against Black people, and an emblem of the racial double-standard in the justice system. If he’d been Black, the argument went, police surely would have shot him. Meanwhile, conservatives celebrated a classic “good guy with a gun,” a patriot who’d come to defend a city under siege. After a televised trial that lasted over two weeks in 2021, a jury found that Rittenhouse had acted in self-defense. Rittenhouse famously burst into tears and fell to the floor when the jury forewoman read the not guilty verdict.

With help from Jillian Anderson, a former “Bachelor” contestant turned publicist, Rittenhouse immediately took a victory lap on the right-wing media circuit that had embraced him within hours of the shooting. He gave his first interview to Tucker Carlson, who had embedded a production crew with Rittenhouse’s legal team during the trial and created a Fox Nation documentary about “Saint Kyle.” On the day of the verdict, former president Donald Trump issued a statement saying, “Congratulations to Kyle Rittenhouse for being found innocent of all charges. It’s called being found not guilty—and by the way, if that’s not self-defense, nothing is!”

In the heady days after the verdict, Rittenhouse met with Trump at Mar-a-Lago and Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) offered him a congressional internship. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) introduced legislation to give him a congressional gold medal. (To date, she’s the only sponsor of the bill.) The conservative youth group Turning Point USA welcomed Rittenhouse with fireworks, confetti, and a standing ovation when he took the stage at its annual conference. Conspiracy theorist Jack Posobiec led the crowd in chants of “Kyle! Kyle!”

The Montgomery County fairgrounds building where Rittenhouse appeared at the Rally Against Censorship was little more than a cavernous metal warehouse with a concrete floor. It had all the glamour of an aircraft hangar, but it had been available after the brewery canceled the original event, allowing it to go on as scheduled. Defiance Press authors were stationed around the room ready to sign books. Here was Dr. Rob Bryant, with Fraud President, a novel about “election integrity.” Here was Troy Wilson, the rare Mother Jones reader at a right-wing gathering, plugging Fake News: A Novel. At one end of the room, a stage had been constructed with a podium in front of a backdrop of the Alamo. Armed attendees sporting the inevitable Trump regalia and “Make Texas a Country Again” hats enjoyed the free pizza and swag from groups like the Montgomery County Tea Party that had set up tables in the back.

After a series of speeches from Daniel Miller, founder of Texit, the Texas secessionist movement, and several Defiance authors, company founder David Thomas Roberts took the podium to introduce Rittenhouse. Wearing a fringed-sleeve suede jacket, dark cowboy hat, and brandishing the long musket featured in the publishers’ logo, he welcomed “all you deplorables, despicables, outlaws, insurrectionists, anti-vaxxers, tea party insurrectionists, conspiracy theorists, domestic terrorists, whatever you want to call us.” He spent a few minutes congratulating himself for allowing the fake news into the event—“we didn’t censor ‘em,” he bragged—before proceeding to trash all the reporters who’d covered the controversy over the brewery canceling the rally, calling one from the Texas Tribune “a piece of shit.”

Finally, Roberts introduced Rittenhouse, “an insightful young man.” He said he’d gotten to know Rittenhouse and his girlfriend when they visited him at his ranch. After receiving a standing ovation, Rittenhouse took a seat in front of the Alamo, which glowed like a gold shrine behind him.

Unlike the others, Rittenhouse did not give a speech. He held a question and answer session with Cassandra Spencer, a former Project Veritas undercover operator and author of Impact: How I Went Behind Enemy Lines In Our Struggle Against The Far Left. Spencer had a tough assignment: prying sentences out of someone barely out of high school whose only claim to fame is having shot three people and gotten away with it. Rittenhouse conceded that as a 20-year-old, “I don’t think my life is that interesting.” Before coming onstage, he explained, he “was back there playing Minecraft.”

With gentle prodding from Spencer, Rittenhouse offered up a litany of familiar grievances about the media. “There are people who want to kill me because of what the media has said about me,” he told her. He described walking to the convention center for a Turning Point USA conference when “some car sped past me screaming ‘murderer.’ People want to hurt me. They want to hurt my loved ones.” Thanks to the media, he said, people think “I’m that guy who killed Black people.” (The people he killed were white.) His whole trial was televised, but he insisted the media were not getting the facts of his story out. (Rittenhouse refused to do any interviews with the few reporters in the room, even though I’d asked for one in advance.) Spencer was a deft interviewer, but Rittenhouse answered her questions like he was filling out one of those rubrics elementary school kids use to learn essay writing. Prompt: “Explain how censorship has played a role [in your life].” Answer: “Censorship has played a major role in my life by taking my supporters off Twitter.”

His lackluster performance might be one reason why his attempt to pursue a career as a persecuted free-speech warrior has floundered. In February 2022, Rittenhouse announced the launch of the Media Accountability Project, a limited liability corporation that would help bring libel suits against people he believed had defamed him. “We’re looking at quite a few politicians, celebrities, athletes. Whoopi Goldberg’s on the list,” Rittenhouse told Tucker Carlson on Fox News. “She called me a ‘murderer’ after I was acquitted by a jury of my peers… We’re going to hold everybody who lied about me accountable, such as everybody who called me a white supremacist.”

It's time to hold the worst offenders in our media accountable in court for their malicious and defamatory lies. Donate: https://t.co/U4NBli1bvD pic.twitter.com/IxuUYfF9Hf

— Kyle Rittenhouse (@ThisIsKyleR) February 22, 2022

To help raise money for the project, Rittenhouse launched a video game in which gamers could play him and shoot turkeys representing “fake news.” “The media is nothing but a bunch of turkeys with nothing better to do than push their lying agenda and destroy innocent people’s lives,” he said in a promotional video for the game, which he sold on his website for $9.99.

Then in June 2022, Rittenhouse prompted another flurry of media coverage when he announced that he’d hired the attorney Todd McMurtry to represent him. McMurtry represented Covington Catholic student Nicholas Sandmann in his defamation lawsuits against the Washington Post and other news outlets over their coverage of his encounter with an indigenous man on the National Mall during the anti-abortion March for Life in January 2019. “I’ve been hired to head the effort to determine whom to sue, when to sue, where to sue,” McMurtry, told Fox News Digital about his new client, saying that it’s “pretty much assured that there’s probably 10 to 15 solid” cases against “large defendants.” Top on his list, he said, was Facebook and its founder Mark Zuckerberg, who had called Rittenhouse a “mass murderer.”

The Media Accountability Project didn’t last a year. Nevada corporate records show it was officially dissolved in January 2023. I asked McMurtry whether he’d filed any suits on behalf of Rittenhouse. “We haven’t filed any suits at this point,” he admitted. Any plans to file suits? “That’s confidential.”

Convincing a jury that the media, and not Rittenhouse himself, was responsible for damaging his reputation would be a heavy lift. After all, there’s a reason so many people associated Rittenhouse with white supremacists.

Not long after he was released on bail, Rittenhouse was photographed wearing a “Free as Fuck” T-shirt and drinking beer at Pudgy’s Pub with members of the Proud Boys, the far-right extremist group. Several of the group’s members are currently on trial for sedition for their role in the Capitol insurrection, including former chairman Enrique Tarrio, who once sported a “Kyle Rittenhouse did nothing wrong!” T-shirt and lunched with Rittenhouse in Miami shortly after the insurrection. In the Wisconsin pub, Proud Boys serenaded Rittenhouse with their official song “Proud of Your Boy,” from the Disney movie Aladdin. He posed for photos with them flashing the white power sign.

The Pudgy’s episode prompted prosecutors to ask the judge to ban him from cavorting with militia groups or white supremacists while he was out on bail awaiting trial. His lawyers contended in court filings that Rittenhouse was not and had never been a member of any such group. Indeed, there’s no evidence that he was, but people from those groups still seem to make up some portion of his fan base.

These look just like the people who stormed the Capitol on January 6, I thought when I looked at the attendees who’d finally started to fill in some of the many empty seats at the Rally Against Censorship. Then I realized I was sitting directly behind about a half-dozen men sporting Proud Boys swag and pounding cans of beer from a case of Coors Light they’d brought for the occasion. After a woman sang the National Anthem to kick off the event, one of them raised his arm and flashed the “OK” white power sign.

“Do you still feel like you’re still having trouble from getting the truth out?” Spencer asked Rittenhouse as the conversation in Conroe turned to Big Tech. “Yes, I think so,” he responded. “Especially Instagram, I simply can’t seem to grow that many followers there.” The implication of course was that his antagonist, Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg, was conspiring to suppress his message. But it’s also possible that there’s just not that big of an appetite for his Insta feed, which consists almost exclusively of fundraising appeals.

In comments on his posts, even supporters seem weary. “Don’t become this person,” writes a rapper named Chad. “I love you just as much as the next person. I care about your rights and 2A just as much as the next person… This ask seems like you are taking advantage of all of us now.”

“’Click here to help Kyle Rittenhouse defeat the left’ is a really lazy and tacky thumbnail,” complains a man named Scott. “I’m super conservative and love the ideals you seem to support as well, but when you post something that looks so much like a money grab it’s hard not to believe it is.”

Yet in Conroe, Rittenhouse blamed Big Tech censorship for his lackluster fundraising. Even before his trial, he explained, GoFundMe had kicked him off the platform, so he’d been relegated to soliciting funds through the Christian site GiveSendGo. His current fundraising goal there is listed at $500,000. As of March 7, it said he’d raised more than $214,000.

Many supporters seem to believe that he’s already cashed in on his legal ordeal, and why wouldn’t they? When he landed on the stage like a rock star at the Turning Point USA conference in 2021, the group’s founder, Charlie Kirk, told the audience, “One last thing for all the media watching: Kyle Rittenhouse is about to be super rich, so you better be careful about what you write.” Rumors have been circulating for more than a year that Rittenhouse won a $22 million settlement with “The View” over Whoppi Goldberg’s comments. No such lawsuit or settlement ever happened.

Late last year, Rittenhouse made some TikTok videos with his new girlfriend, Skyler Bergoon, where they lip-synched Taylor Swift and High School Musical 2 songs.

I changed my mind. Send him to prison. pic.twitter.com/ALgG8UVRrC

— Daniel Godfrey (@danielgodfrey) September 10, 2022

Then in November, he retweeted a photo of the leggy blonde model sitting in his lap. The social media backlash was swift, suggesting that Bergoon, a former North Carolina beauty pageant contestant, was only with him to juice her influencer revenue. “My girlfriend is not a gold digger,” Rittenhouse fired back in a tweet. At the censorship rally, Rittenhouse rejected any suggestion that he’d made bank from killing people. “I am not a rich dude,” he told Spencer.

He did raise more than $630,000 during his trial through GiveSendGo in a separate effort, and his first lawyers raised at least $2 million to pay his bail from a host of right-wing luminaries. After he was acquitted, the bail bond was supposed to be refunded to whomever posted it, prompting a feeding frenzy over just who should get the money. Ultimately, Rittenhouse got back $925,000 that was put into a trust. But his legal fees were extensive, and the bills continue to pile up. “To say that he got rich, this was bullshit,” Mark Richards, his lawyer, told me. “The defense, between experts and lawyers’ fees, cost a lot of money.”

The family of Anthony Huber, the second man Rittenhouse shot and killed, is suing Rittenhouse for wrongful death in Wisconsin. Rittenhouse has spent the past year essentially evading service in the case—an investigator alleged in court filings that Rittenhouse had gone so far as to seed public records databases with fake addresses so the process server couldn’t find him. But on February 1, a federal judge ruled that most of the case could move forward.

Two weeks later, the third man Rittenhouse shot, Gaige Grosskreutz, amended an earlier lawsuit he’d filed in 2021 against Kenosha law enforcement to include Rittenhouse as a defendant. The plaintiffs in these cases have an uphill battle, but the lawsuits mean Rittenhouse’s legal woes will continue, along with his fundraising. News of the Grosskreutz suit scored Rittenhouse another visit to Tucker Carlson’s show in early March, where he pleaded for donations and warned viewers cryptically that if “they can come after me, they will come after you.” The ticker on his GiveSendGo page subsequently jumped another $80,000 over the next few days.

Kyle Rittenhouse is on Tucker asking people to send him money for the lawsuit against him: “This lawsuit is very frustrating and it’s upsetting .. If they can come after me, they will come after you.” pic.twitter.com/P51dLzNAna

— Ron Filipkowski 🇺🇦 (@RonFilipkowski) March 2, 2023

As the question and answer session started to wind down at the censorship rally, Spencer asked Rittenhouse what he would tell his 16-year-old self, knowing what he knows today. An easy answer to this great question was, “Stay home!” That’s what he told Ashleigh Banfield right after he was acquitted. “If I could go back, I would not have gone there,” Rittenhouse said of that fateful night in Kenosha.

But after a year on the right-wing circuit, Rittenhouse has shaved off any introspection from his public commentary, opting instead for conservative buzzwords about gun rights and the left. “What I would tell myself is everything can change,” he said finally in answer to Spencer’s question. “You can be attacked just for simply doing the right thing, standing up for the Constitution, protesting Planned Parenthood, going to a censorship rally.”

Perhaps it’s because Rittenhouse looks so young, but on stage he projects the image of the sweet kid conservatives insist he really is. He doesn’t seem so different from the chubby-cheeked boy who peered out of photos wearing a fireman’s hat or other uniforms from the various “cadet” programs he had once participated in. Rittenhouse wasn’t even old enough to vote or buy beer or rent a car when he joined the grown men cosplaying Call of Duty during the unrest in Kenosha. He’d been bullied at school. His divorced mother struggled to keep the family afloat. They’d survived evictions, lived in a shelter briefly, and struggled to make ends meet. Rittenhouse had been working part-time as a lifeguard not long before the shootings. His struggles suggest he may have been exceptionally vulnerable to the madness of 2020, when right-wing media and conservative politicians had normalized the insane notion that ordinary men should wander the streets unimpeded while carrying assault weapons.

His youth stood out when he burst into tears on the stand after hearing the not-guilty verdict and he seemed overcome by the gravity of everything that had happened. Shortly after the verdict, he talked publicly about seeing a therapist, and being treated for PTSD. He confessed to suffering from nightmares and panic attacks. Those personal revelations have long since disappeared from his stump speech.

In public appearances, he seems baffled by the rest of the world’s refusal to exonerate him and embrace the Kenosha jury’s conclusion that he’d acted in self-defense. The problem, of course, is that the verdict didn’t absolve him of taking an assault rifle into a violent protest in the first place. “The conscious choice to impose a risk—even permissible risk, as in the case of driving—opens a person up to moral liability,” the Oxford professor moral philosophy Jeff McMahan told the New Yorker in 2017. “People who are not culpable can nevertheless be responsible.”

Former First Lady Laura Bush was also 17 when she ran a stop sign and killed another 17-year-old driver. In a memoir, she wrote of losing her faith afterwards, and being “wracked by guilt for years after the crash.” Bush suffered in silence for more than 40 years. “Most of how I ultimately coped with the crash was by trying not to talk about it, not to think about it, to put it aside,” she wrote. “Because there wasn’t anything I could do. Even if I tried.”

Killing those men in Kenosha is all Rittenhouse talks about. From the beginning, Rittenhouse has been preyed on by right-wing opportunists. Bad actors anointed him a hero and absolved him of culpability. They’ve pushed him in front of the klieg lights and encouraged his wildly misguided schemes like the video game or his attempt to start a YouTube channel devoted to reviewing guns. And they’ve nudged him to embrace the kind of extremist rhetoric that’s required to feed the beast.

In late February, Rittenhouse appeared on Donald Trump Jr.’s new Rumble show, “Triggered,”where he bantered with the former president’s son about “Sleepy Joe” and how to destroy CNN. His star-struck baby-faced expression contrasted sharply with the antisemitic conspiracy theory Rittenhouse invoked during the interview. Leaning back in his chair, he told Trump confidently that during his murder trial, he’d been “up against these George Soros-funded prosecutors.” When Trump asked if the prosecutors were getting “backend donations” from the famous Jewish billionaire, Rittenhouse responded, “I guarantee it.”

I asked Kenosha County assistant district attorney Thomas Binger, who led the Rittenhouse prosecution, whether he’d ever gotten any Soros money. “I suppose it’s fun for him to imagine that he’s the target of some nefarious global cabal, but unfortunately there is absolutely no truth to his accusation,” he told me. “Our office receives all of its funding from the taxpayers of Kenosha County and the State of Wisconsin. I am a State employee and have not received any compensation related to this case from any other source other than my regular paycheck.”

In Texas, as Rittenhouse spoke in front of the glowing Alamo backdrop, I looked for even a hint of remorse. Any hope of that probably died the minute he let Tucker Carlson embed with his legal team. Publicly breaking even a little from the party line of relentless victimhood and rah-rah Second Amendment purism would threaten his prospects on the right-wing circuit where he’s staked his fortunes. It could even represent a tacit admission of guilt in the civil suits against him. He’s dug in.

Looking at the paltry audience for his much-hyped Conroe appearance, I wondered just how long Rittenhouse can keep making a public spectacle of himself—or why he even wants to. “Kyle’s got to make a living but my advice is to crawl under a rock and live your life anonymously,” Richards, his attorney, told me. “Obviously, people don’t take my advice.”

No one I spoke with at the Rally Against Censorship seemed all that excited to see him. Even the Proud Boys got bored. They left before he finished talking, flashing the white power sign to him as they exited the building.