Mother Jones; Thomas Brey/picture-alliance/dpa/AP; Unsplash

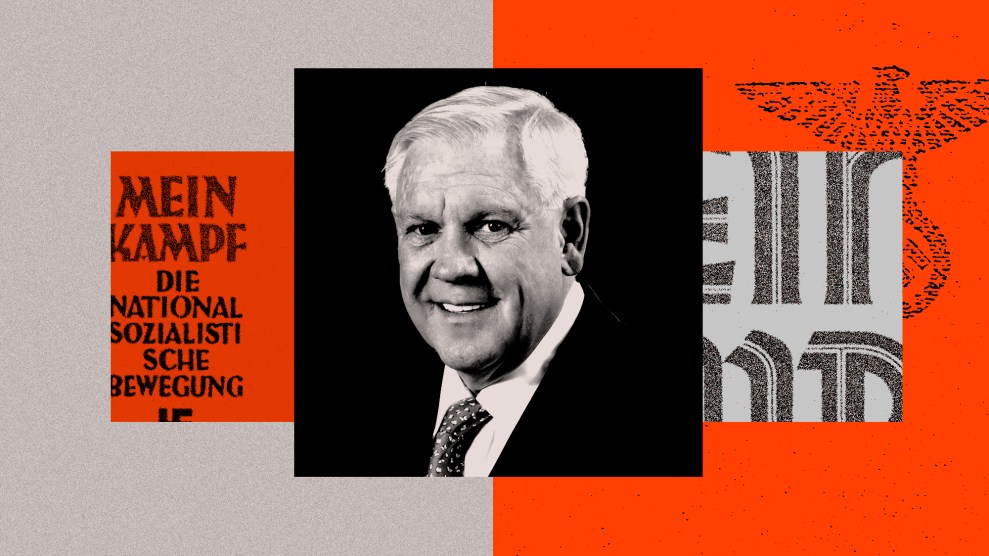

Harlan Crow—the second-generation Texas billionaire who lavished Clarence Thomas with expensive getaways in the Adirondacks and Indonesia, purchased the Thomas family home, and let the Supreme Court justice’s mother continue to live there rent-free—has a passion for a particular kind of horticulture.

At his $55-million estate outside Dallas, Crow has built what he calls the “Garden of Evil.” It is a sculpture garden of “deposed dictators” and the like, which Crow has sourced, with the help of a resourceful fixer named Tie, from a variety of mostly former communist nations. There’s a Lenin, a Ceausescu, and a Castro. Hosni Mubarak is there. (Yes, he is dead, I checked). Josip Tito and Karl Marx are nearby. There’s even one of Stalin and Mao, talking to each other.

You may think it is strange, but it’s actually—according to a number of people who have taken money from Crow in the past, and even a surprising number of people who haven’t—an extremely normal thing to do to set aside a plot of land and, as Ben Shapiro put it, “remember the things you hate.” When I was growing up, we put a little statue of St. Francis up by our flower bed. But it came from a store, and not Romania, and it was, I can assure you, with respect.

If you cannot truly relate—or even fully process the surplus of inherited real-estate wealth that flows aimlessly through such a project—you can at least recognize a general theme there: Fallen strongmen, the ephemerality of power, and so on. It is a monument to the hubris of leftist ideologues. Or maybe it is simpler still; Forbes, in a 1996 profile, described the collection as simply “Crow’s victory garden.” He was inspired to begin collecting after the end of white apartheid rule in Zimbabwe. “In the back of my mind I have a picture of Cecil Rhodes being pulled down,” he said then. “I thought then how sad it was that that stuff might not be preserved.”

Again, sort of a weird reaction to the toppling of Cecil Rhodes, but you can’t deny that a man so committed to British imperialism he wanted to retake the United States at least fits the mood.

But there is one statue that’s often referenced in connection to the garden that does seem a bit unlike the others. “Perhaps the strangest part of the collection,” the New York Times reported in 2003, “is the bust of [Gavrilo] Princip.” It arrived in four pieces, the paper noted, and without a nose.

Princip, for those who have not read a history book or watched The King’s Man, was the Bosnian Serb who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, in 1914, after a bunch of his friends had failed to do so earlier that day. In those history books (and The King’s Man) Princip is often depicted as the “spark” that ignited the “powder keg” that became the First World War: The Austro-Hungarians attacked newly independent Serbia in response, which, because of existing alliances, quickly led to everyone else in Europe attacking each other. Still, blaming it all on Princip is too easy. If you had a lighter that sparked like the Sarajevo assassination plotters, you’d throw it out; the powder keg is really the most important part of the powder-keg metaphor. It seems at least a little unfair to blame a bumbling assassin for the fact that two of Queen Victoria’s grandsons went to war with another one of Queen Victoria’s grandsons.

I’m not saying he should have done it, and you never really want to attach yourself too strenuously to an emblem of Serbian nationalism, but his inclusion does sort of go against the script. Crow keeps monuments to the toppled heads of state. Princip toppled a future head of state. The empire subsequently fell. The guy there should be a statue of is the Archduke! He was, after all, a Habsburg—one of the all-time fucked-up European ruling families.

I am not the only person willing to admit that Princip’s presence is a little odd. Crow’s statue guy, Tie Sosnowski, bought Princip from a museum in Sarajevo during the Balkan war (a buyer’s market). He discussed the acquisition in that interview with the Times. “He’s kind of out of place among the other guys,” Sosnowski acknowledged. “But he captures what was going on at the century’s beginning and end.” It brings the room together.

In recent weeks there has been a tendency—which I am guilty of—to overanalyze Crow’s garden and his indoor galleries, which include a collection of paintings by Hitler. With Congress unlikely to take any steps to address the brazen corruption and impunity at the heart of the Thomas story, what else are we supposed to do? But a lot of it is sort of dancing around the obvious: This is less an indicator of any coherent set of beliefs than it is of the futility of estate taxes, and the corresponding way that wealth, if allowed to accumulate in a deep enough pit, develops its own gravitational power to attract weird shit. When you are buying-another-Hitler rich, your money has stopped even feeling like money; it should be its own special tax bracket. So long as it’s not, there will always be room for growth in the “Garden of Evil.” I hear a new Cecil Rhodes just came on the market.