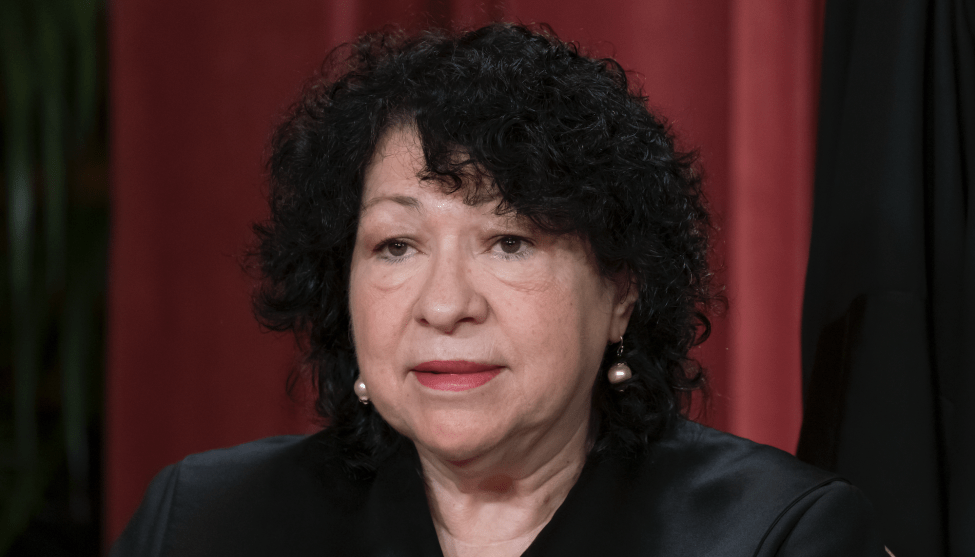

Jacqueline Martin/CNP/ZUMA

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority banned race-conscious admissions policies at colleges and universities on Thursday, ruling that using race as an admissions factor violates the Constitution’s equal protection clause. The decision invalidates the University of North Carolina and Harvard’s systems for making up their student body, and will, more broadly, make higher education whiter and society less equal.

While the decision pushes back the country’s ability to remedy the affects of slavery and Jim Crow, in his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts carved out what could be interpreted as a small loophole in his decision: “Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise,” Roberts wrote at the end of his opinion.

But Roberts himself insists that this is not a backdoor to affirmative action. “A benefit to a student who overcame racial discrimination, for example, must be tied to that student’s courage and determination… In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race.”

In the immediate aftermath of the court’s ruling, it is unclear if Roberts has weakened his own opinion by allowing consideration of race in some instances or, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent, has simply put “lipstick on a pig.” Either way, the line supports the notion that Roberts was forced by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s questions to grapple with how a truly color-blind admissions policy would be both unworkable and unfair.

Jackson raised this point during oral arguments in October, where she gave the following hypothetical:

The first applicant says: I’m from North Carolina. My family has been in this area for generations, since before the Civil War, and I would like you to know that I will be the fifth generation to graduate from the University of North Carolina. I now have that opportunity to do that, and given my family background, it’s important to me that I get to attend this university. I want to honor my family’s legacy by going to this school.

The second applicant says, I’m from North Carolina, my family’s been in this area for generations, since before the Civil War, but they were slaves and never had a chance to attend this venerable institution. As an African American, I now have that opportunity, and given my family — family background, it’s important to me to attend this university. I want to honor my family legacy by going to this school.

So, Jackson queried, under a race-blind policy, would the school be forced to ignore the story of the Black applicant but credit the story of the white one? This situation would likely cause “more of an equal protection problem than it’s actually solving,” she explained at the time.

In a dissenting opinion today, Jackson expanded on the hypothetical. She named the two applicants John and James. John’s family has attended the UNC for seven generations; James would be the first in his family to enroll. Jackson’s dissent, in pages of detail, airs the tortured history that brought John and James to this point, from slavery to Jim Crow, to truly explain the disparities—not just in their individual experiences, but in those of their ancestors.

Most likely, seven generations ago, when John’s family was building its knowledge base and wealth potential on the university’s campus, James’s family was enslaved and laboring in North Carolina’s fields. Six generations ago, the North Carolina “Redeemers” aimed to nullify the results of the Civil War through terror and violence, marauding in hopes of excluding all who looked like James from equal citizenship. Five generations ago, the North Carolina Red Shirts finished the job. Four (and three) generations ago, Jim Crow was so entrenched in the State of North Carolina that UNC “enforced its own Jim Crow regulations.” Two generations ago, North Carolina’s Governor still railed against “‘integration for integration’s sake’”—and UNC Black enrollment was minuscule. So, at bare minimum, one generation ago, James’s family was six generations behind because of their race, making John’s six generations ahead.

In a separate dissent, Sotomayor warns that Roberts’s concession is merely an exercise in trying to look good, and not one that will actually soften his ruling. “This supposed recognition that universities can, in some situations, consider race in application essays is nothing but an attempt to put lipstick on a pig,” she writes. “The Court’s opinion circumscribes universities’ ability to consider race in any form by meticulously gutting respondents’ asserted diversity interests. Yet, because the Court cannot escape the inevitable truth that race matters in students’ lives, it announces a false promise to save face and appear attuned to reality. No one is fooled.”