West Wendover, Nevada, has long played a special role for residents of my home state of Utah: It’s where they go to sin. Just 122 miles from Salt Lake City, the tiny border outpost offers cheap booze, big casinos, and more recently, legal weed—all the things you can’t find in the land of Zion. But for the casinos, the seven square miles in the middle of nowhere that constitute West Wendover would not exist except as a pit stop in the vast empty space between Salt Lake and Reno. Instead, its population of 4,500, more than triples on weekends when party buses from Salt Lake and Ogden deposit thousands of mostly senior citizens into the lobbies of its five casinos.

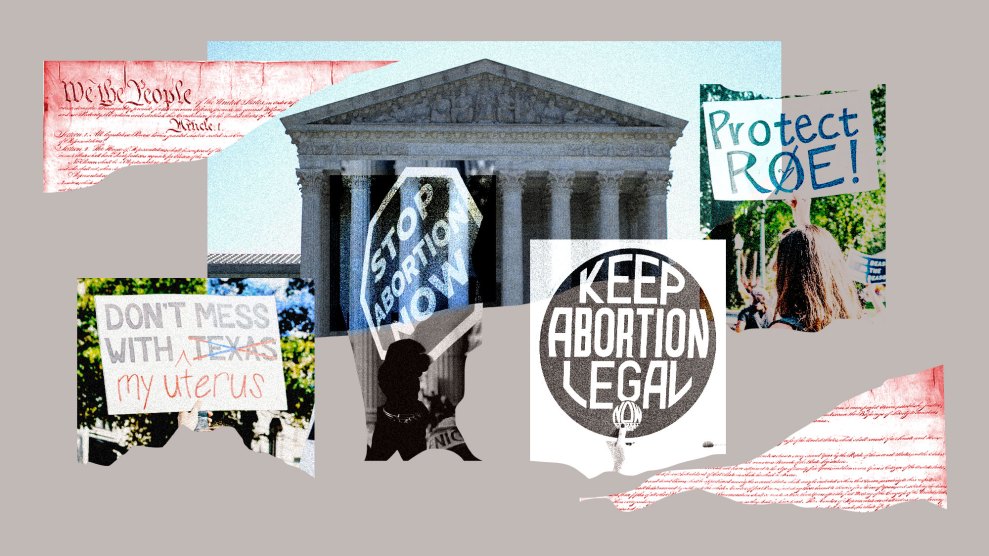

So last year, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade with its decision in the Dobbs case, thus triggering a state law that would immediately ban abortion in Utah, I figured it was only a matter of time before someone opened a reproductive health clinic in West Wendover. I wasn’t alone in seeing the potential.

Since 2021, Planned Parenthood Mar Monte had been anticipating the end of the constitutionally protected right to an abortion. With 34 health centers already operating in California, the group saw Nevada—where the procedure is legal up to 24 weeks and beyond if medically necessary—as another safe haven for people from the other states that would inevitably ban abortion when Roe fell. Nevada’s laws are so liberal that minors can obtain the procedure without parental consent. As a result, even before the Dobbs decision leaked in the spring of 2022, PPMM had started preparing by expanding its services in places like Reno, where it already had one clinic.

West Wendover’s location on the border of a state that was likely to ban abortion made it a natural expansion site. And yet, in March, the West Wendover City Council voted 4 to 1 against giving PPMM a permit to open a clinic, a decision that baffled many longtime residents and Utah observers alike. “I was so angry I cried,” says Kathy Durham, a former West Wendover city council member and high school teacher. “I could not believe that they shut this down.”

I, too, was shocked by the decision that seemed so at odds with the city’s permissive reputation. But then again, I hadn’t been to Wendover in decades. So in April, I took a road trip to try to understand why a city built on vice drew the line at an abortion clinic and what the broader implications of that decision might foreshadow for reproductive rights elsewhere in the West.

Despite Utah’s dominion by the LDS church, people from all over the Mountain West have long made their way to Salt Lake City for the abortion care they can’t get elsewhere. That trend has intensified as neighboring states have restricted abortion access. In 2021, for instance, Planned Parenthood performed 2,554 abortions at its three Utah clinics. Only 51 of those clients were from Idaho. But in 2022, after Idaho passed one of the strictest abortion bans in the country—forbidding abortion in all stages of pregnancy— the Utah clinics saw a 70 percent increase in Idaho clients.

At the same time, Utah has joined other red states in making abortion harder to obtain. In 2012, the legislature imposed the country’s first 72-hour waiting period, which caused a big drop in the number of out-of-state residents terminating pregnancies there. In 2020, the Utah legislature passed a trigger law that would immediately ban most abortions in the state as soon as the Supreme Court overturned Roe.

The trigger law has been on hold while the state Supreme Court hears a challenge to its constitutionality. Meanwhile, state lawmakers passed a new measure in March that would shutter all abortion clinics, while allowing a few procedures to take place in hospitals. That new law, too, is on hold after Planned Parenthood of Utah sued. At this point, abortion remains legal in Utah for up to 18 weeks. But given the gerrymandered GOP stranglehold on the legislature and the state’s conservative courts, eventually, abortion services in the state will be severely curtailed.

Once that happens, for the 2.6 million people living in northern Utah, plus many of those who live in southern Idaho and parts of Wyoming, the closest abortion clinic will be at least a six-hour drive away in Las Vegas or Glenwood Springs, Colorado. “As we’re looking for options for our residents, you have to look at the number of mountain passes you have to cross,” especially in the winter, says Jason Stevenson, director for public policy at the Planned Parenthood Association of Utah.

The two-hour drive from Salt Lake to Wendover, however, is straight and flat, and the speed limit is 80 miles an hour. I made that drive on a clear day in April, cruising west past the Great Salt Lake and across the salt flats towards the Bonneville speedway, where hot-rodders have been chasing land speed records for more than a century. Civilization mostly vanished once the lake did. The most notable roadside attractions were billboards for the Southern X-Posure strip club in West Wendover.

As I approached the town, I turned off I-80, passed through a rocky crevasse, and emerged onto Wendover Boulevard, the town’s one and only main drag. The 1.5-mile-long commercial strip is so podunk that it has more stop signs than stop lights. Dominated by five big casinos, its only other significant landmarks are the beloved Lee’s Discount Liquor, where Utahans load up on the booze sold only in state liquor stores at home; the turnoff for the weed dispensary; and the neon giant, Wendover Will, described by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s largest mechanical cowboy. The Planned Parenthood clinic would have been just around the corner from Will, two miles from the Utah border.

The cityscape of West Wendover, Nevada, featuring “Wendover Will.”

Dominic Chavez/The Boston Globe/Getty

Like Las Vegas, West Wendover is a company town. Almost everyone works in the casinos that are owned by the same two corporations. But the casinos have worked hard to keep out the strong unions that represent workers in Las Vegas. West Wendover differs from Las Vegas in other significant ways as well, and not just because it’s so small.

On the map, West Wendover is a dot surrounded by the vast Elko County, one of the most conservative counties in Nevada. Nearly 80 percent white, Elko County has more in common politically with Tooele County, just over the Utah border, than Clark County, where Las Vegas resides. In 2008 and 2012, West Wendover voted along with the rest of Elko County—and Utah—for the Republican presidential candidates. But in 2016, the town’s political leanings diverged from the county when it voted for Hillary Clinton. In 2020, Joe Biden won West Wendover by 10 votes—even as Elko County, yet again, went all in for Trump.

The Democratic shift has its roots in the late 1980s, during a casino construction boom that spurred a wave of immigration primarily from one place: Zacatecas, Mexico. By 1990, West Wendover had officially become more than 50 percent Latino; today that figure is more than 60 percent. In 1999, West Wendover elected its first Latino city council member, and today, four out of the five council members are Latino, a majority that has existed on and off since 2012. In 2016, those trends helped elect 25-year-old Daniel Corona, an openly gay Latino Democrat, as West Wendover’s mayor.

Paradoxically, the same demographic changes that helped swing West Wendover blue contributed to the city council rejecting Planned Parenthood this spring. “The population of Latinos in West Wendover are folks who were immigrants from Mexico and now have children now becoming the leaders of the community,” says Mark Hugo Lopez, director of race and ethnicity research at the Pew Research Center. It’s different from Las Vegas, he notes, “where you have people who’ve moved from Los Angeles to work in the casinos.”

He says polling data shows that Latino immigrants are more lukewarm on abortion rights than US-born Latinos, with 48 percent of immigrants saying it should be legal, compared with about 60 percent of all Latino adults. “If folks are still closely tied to their Mexican roots,” Lopez says, they may vote Democratic but their views on abortion are “definitely going to be tied to Catholicism.”

Corona was two years into his second four-year term when Planned Parenthood first approached him about opening a clinic in Wendover. He welcomed the proposal because health care was his constituents’ number one concern. The town has no hospital and only a poorly-staffed federally funded clinic. Even bonuses from the casinos have failed to lure a full-time doctor. As a result, city residents must drive two hours to Salt Lake City to get most healthcare services. Anyone having a heart attack in a casino, which happens with some frequency, has to be airlifted there, and even then, it’s a 30-minute helicopter flight. “Every family in Wendover has someone in their family who was born in the back of the ambulance” on the way to Salt Lake, Corona told me. This includes his sister, whose husband was born in the back of a car on the salt flats.

Planned Parenthood Mar Monte had offered to remedy some of these problems. It already ran a number of full-service primary care clinics in California, and it promised to bring West Wendover not just reproductive health care but also prenatal care and a full range of medical services, from x-rays to diabetes management. In August 2022, Corona stepped down after six years as mayor to take a job with a Lake Tahoe casino. But the clinic discussions continued under the new mayor, former city council member Jasie Holm, who also supported it.

In early January, Planned Parenthood put down a deposit on an empty lot near the Southern X-Posure strip club and applied to the city for the requisite permit. The city manager concluded that there was no legal reason for West Wendover to reject Planned Parenthood’s application, and the council put it on the agenda for a March 7 public meeting.

Anti-abortion activists from all over the region came out in droves to testify against the proposal, including Deanna Holland, the head of Pro-Life Utah. Jesus Dorado, the owner of a popular Mexican bakery in West Wendover, submitted a handwritten note getting right to the point: “I am against abortions and I would not like to have this facility in our area.”

Local churches that Corona says he never heard from while he was mayor materialized to fight the clinic. Prominent among them: the tiny Blessed Hope church headed up by Pastor Dennis Draves, whose congregation includes Rose Hanson, the wife of Councilmember John Hanson. At the council meeting, in testimony riddled with misinformation, Draves spent 10 minutes talking about fetal development and asserted that “women who abort are 144 percent more likely to abuse their children.”

Former councilmember Kathy Durham had tried to rally the community to support the clinic, enlisting many of her former students. Pro-clinic speakers warned of potential lawsuits and reminded the council of its constitutional obligation to keep church and state separate. “Don’t force your religion on others,” said Lizbeth Raygoza, one of Durham’s former students. One man, Justin Evans, endorsed the clinic because a Salt Lake City Planned Parenthood had filled his wife’s contraception prescription that a West Wendover pharmacist refused to provide. “It was essential to our family succeeding,” he said.

But the anti-choice crowd dominated the meeting, with many bemoaning the idea of Wendover becoming a destination for “abortion tourism.” After some of the younger Latina women testified in favor of the clinic, Durham says an older woman standing against the wall would “call them murderers in Spanish.”

After two hours, Hanson called the vote: The permit went down 4 to 1, with Hanson in the majority. Two of the “no” votes were cast by more conservative Latino council members elected in November when they replaced Durham and another more liberal Latino member who was term-limited. “I still am beside myself at what they did,” Durham says. “I thought the council was in such a good place, I didn’t run, and now I’m regretting it.”

When I drove by a month later, a “For Sale” sign marked where the clinic should have been, and the proposal appeared dead in the water. “Planned Parenthood Mir Monte is exploring all options and have retained counsel,” Lauren Babb, PPMM’s vice president for public affairs later told me. “That’s all we’re able to share.” The radio silence from Planned Parenthood, however, did not deter outside anti-abortion activists from descending on West Wendover in the hopes of turning it into a “sanctuary city for the unborn.”

The agenda for the West Wendover city council meeting I attended the following month promised a soporific lineup of mundane municipal affairs: reports from the police chief and the fire department, the declaration of “Youth Law Awareness Day.” Abortion was nowhere on the list. Nonetheless, Mark Lee Dickson, a Texas anti-abortion activist, had flown to Salt Lake and driven across the desert to attend the meeting. He hadn’t come to gripe about the public works budget, or even to fight the Planned Parenthood clinic. Instead, he made the trek to lobby the city council to pass an ordinance that would ban abortion everywhere in West Wendover.

The ordinance was written by Jonathan Mitchell, the former Texas solicitor general who was the brains behind Senate Bill 8, the 2021 Texas Heartbeat Act. That law imposed a near-total abortion ban in Texas and allowed private citizens to sue anyone who provides an abortion or helps someone else get one and win at least $10,000. The unusual enforcement feature had prevented judges from reviewing it, including the Supreme Court, which let it fly.

Dickson’s proposed ordinance is likewise a novel approach to banning abortion in places like Nevada with strong state laws protecting reproductive rights. It relies on the 150-year-old Comstock Act, a federal criminal statute that hasn’t been enforced in decades but, in theory, bans the mailing and receiving of abortion drugs and medical equipment used in the procedure.

Since he started in 2019, most of the ordinances Dickson has won have been in cities in Texas, a state that already severely restricted abortion, rendering his efforts essentially meaningless. Recently, however, he scored victories in a couple of New Mexico border towns, where clinic operators were attempting to find new locations to handle the influx of women from Texas seeking abortions. In March, New Mexico Governor Michele Lujan Grisham (D) signed a bill expressly forbidding such actions by local governments. The state attorney general has sued a couple of the jurisdictions whose anti-abortion ordinances violate the state constitution, and the state Supreme Court blocked their implementation.

Nevada law also prohibits local jurisdictions like West Wendover from creating such ordinances that would deprive residents of rights guaranteed by state law. But banning abortion in border towns isn’t really Dickson and Mitchell’s main objective. “They’re looking for opportunities to manufacture conflicts, in states where the ordinances obviously conflict with state law,” explains Mary Ziegler, a UC Davis law professor and author of several books including Roe: The History of a National Obsession. She says Mitchell and Dickson are using places like West Wendover to kick up lawsuits they hope will serve as a vehicle for the Supreme Court to enact a national abortion ban. “They don’t care about Nevada.”

Indeed, the day before I met him outside the West Wendover city hall, Dickson had been standing in front of the US Supreme Court announcing that Eunice, New Mexico, had just sued the governor and state attorney general to try to enforce its anti-abortion ordinance. The case is a prelude to getting the ordinance into federal court.

Wearing his signature backward baseball cap, skateboard shoes, and a beard without a mustache, Dickson arrived at April’s city council hearing with an entourage that included Blessed Hope Pastor Dennis Draves, whom he’d contacted after reading a quote from him in a news story about the March clinic vote. Draves had hosted Dickson at his church for an interest meeting about the proposed ordinance a few weeks earlier. Standing outside in a bitter cold wind before the meeting, I asked Dickson why he was getting involved in small-town politics so far from home. “People who would be coming here for abortions are from Utah,” he told me with a shrug, as if that explained the matter. “You’ve got people who want to see an abortion-free Wendover.” I was also curious to know who was paying for all of his travel. “The Lord takes care of it all,” he told me, looking skyward, when I asked about his financing.

After the Pledge of Allegiance and other formalities, the council opened its meeting to the general public for brief comments. Five people had signed up to speak—four of them abortion foes. One woman urged the council to pass Dickson’s ordinance “because we know Planned Parenthood will be back.” Then Dickson took the mic.

Texas anti-abortion activist Mark Lee Dickson speaks before the city council in West Wendover, Nevada.

Stephanie Mencimer/Mother Jones

So far, he said, 65 cities and two counties had passed the ordinance he was proposing. “Since the overturning of Roe v Wade,” he said, “we followed the abortion industry into New Mexico where they were seeking to set up shop in Hobbs and Clovis and some other border areas.” Once those communities passed ordinances, he said, the “abortion industry” left town. He promised that if West Wendover got sued for passing an ordinance, Jonathan Mitchell would defend the city pro bono. “It is possible for an ordinance to be passed in this community which keeps abortion out,” he insisted.

Eighteen-year-old Marcos Cerros spoke to the council as the lone supporter of abortion rights. He said that passing Dickson’s ordinance would be “begging for a lawsuit and every member of the city council knows that this town has practically no spare money in its budget. And it’s not a lawsuit that would be won.”

After the meeting, Marcos told me he had become an activist during the pandemic because of the school closings. He and his 22-year-old brother Fernando also testified at the March city council meeting in support of the clinic. As we talked, an older Latino man walked by and gave him a friendly thumbs up. A clinic supporter? “No, he’s the dad of a friend of mine,” Marcos said with a laugh. “He’s against the clinic.” The woman who spoke against the clinic after him in the meeting, he says, is his boss at the casino where he works.

In the lobby, Marcos introduced me to Fernando and his mother, Carmina, a member of the predominantly Latino local Catholic church. He explained that the church is the primary source of information for people who don’t speak English. West Wendover has no Spanish language media, or much local media of any sort, so there’s “Facebook for the older people,” he said, “Snapchat for everybody else.”

Carmina said her church is “cien por ciento” against Planned Parenthood. Nonetheless, she supported the clinic because she had lost a baby while driving to a Salt Lake hospital. Two of her kids were nearly born in the car. She told me that she frequently has to drive co-workers to Salt Lake for medical care. “We don’t have nothing here,” she said.

Just before leaving City Hall for the night, I bumped into Councilmember John Hanson. With a shock of white hair and matching white teeth, Hanson is a jovial fellow known in town as a big-time Trump supporter who likes to race fast cars on the salt flats. He’s lived in Wendover for more than 40 of his 82 years. His wife had testified against the clinic permit in March. I asked him if her activism posed a conflict of interest for him. “She does her thing,” he said. “I’m a CEO Christian—Christmas, Easter, and other holidays.” He says he opposes the clinic because he believes the town doesn’t want it. “We’re a tourism city, but we don’t want this sort of tourism,” he said, adding, “The health care I’m in favor of.”

Border of Utah and Nevada at West Wendover.

Francis Dean/Corbis/Getty

On the way out of town the next day, I stopped at Dorado’s Bakery, whose cheerful owner, Jesus, had written a note to the council opposing the Planned Parenthood clinic. I could understand why he might be against it: The modest aluminum-sided bakery building sat directly behind the lot Planned Parenthood had chosen for its clinic, which would invariably attract bomb threats and protesters who might scare off customers. The bakery also turned out to be across the street from the old house that serves as Blessed Hope church. After buying some delicious tortas from Jesus, I found Pastor Draves in the church serving lunch to about a half dozen white people listening to a presentation by Treion Dally.

Sporting dramatic cat-eye glasses and big hoop earrings that peeked out under her bright red hair, Dally looked Vegas flashy, but the brochures she’d brought revealed a moral crusade. Dally had traveled 400 miles from Fernly, a town outside Reno, where she is the director of the Real Choices Women’s Center, a crisis pregnancy center she started almost 30 years ago. She was at Blessed Hope to help start one in Wendover. “I think every town should be able to give options and to love women and holistically surround the family no matter what decision they make,” Dally told me later. “Even if they chose abortion.”

Crisis pregnancy centers usually set up shop right next door to, or across the street from, an abortion clinic. They deploy highly deceptive means to lure women in and attempt to persuade them to bring their unplanned pregnancies to term. It was, perhaps, inevitable that the result—and possibly the only result thus far—of Planned Parenthood trying to open a clinic in West Wendover would be Christian groups showing up to open a CPC. Wendover currently doesn’t have one. At the same meeting where Mark Lee Dickson made his case for an anti-abortion ordinance, the council heard from a Nevada Department of Health and Human Services representative who described how abused and neglected children were occasionally being housed in local hotels for lack of foster parents.

Corona believes that the vocal anti-abortion forces at the March city council hearing don’t represent the majority of town residents. “One thing the council is going to find out,” he told me, “is that this [clinic] decision was very unpopular within the community,” particularly among young Latinos like the Cerros kids. West Wendover is a young town. The median age there is 28 or 29, Corona says, a full decade younger than the national median. Pew’s Mark Lopez says polls show that nearly 80 percent of Latinos between the ages of 18 and 29 believe abortion should be legal in most cases, making them far more supportive of abortion rights than their parents. “There are a lot of younger Latinos in the community who are fired up now,” Corona told me. “I think next election there might be a lot of surprises.”

Two of the clinic opponents will be up for reelection in 2024, a presidential election year when abortion will be front and center, and Nevada will be a hotly contested swing state. A surge of young Latino voters energized about abortion could make a big difference in the outcome if they decide to turn out, says Gabriel Sanchez, a fellow at the liberal Brookings Institute and an expert on Latino politics in the West. What’s happening in West Wendover, he says, is “really a microcosm of what everybody is paying attention to nationally.”

It wouldn’t be the first time a quiet liberal majority swung an election in West Wendover. In 2018, the city was considering legalizing recreational marijuana. As with the Planned Parenthood clinic, churches vocally opposed the idea, and Councilmember John Hanson was a leading critic. The council voted against it. Seven months later, voters booted Hanson from office, and a few days after the election, the council voted 3-2 to legalize recreational weed. (Hanson got elected again last year.) “There would be no economy if not for sin in West Wendover,” observes Corona with a laugh. “It makes it kind of interesting.”