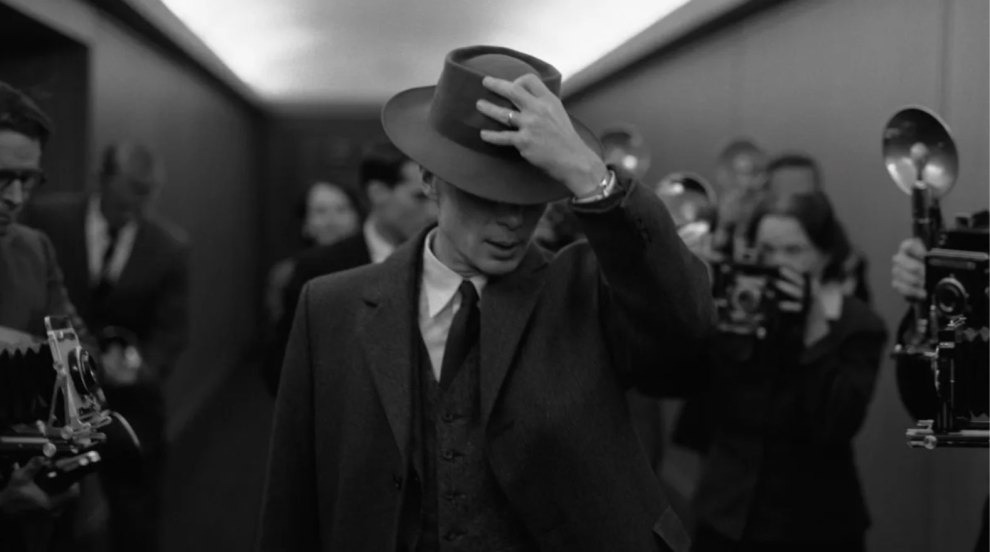

Cillian Murphy as the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. Courtesy of Universal Studios

There is much to admire in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, which opens in theaters on Friday. The directing, script, editing, sound design and acting are all extraordinary. Nolan deserves high praise for tackling this difficult and sprawling subject and raising questions about one of the most sensitive issues in our history, a raw nerve even today: America’s use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which killed at least 150,000 civilians.

Even in a three-hour movie, Nolan had to leave out a lot of vital material, in part because of his secondary focus on Oppenheimer’s infamous security clearance hearing almost a decade after he left Los Alamos. Still, his film omits or downplays several important—even crucial—aspects of America’s 1945 detonations that continue to haunt us today.

Notably, the new film barely touches on arguments that were expressed back then, not in retrospect, against using the bomb. Ditto the deadly radiation the new weapon produced, and the secrecy that surrounded it—starting with the Trinity test, when a radioactive cloud drifted over nearby villagers who were not warned, and were then lied to about the fallout effects. This combination of lethality and secrecy would have extensive and tragic results in the decades after Hiroshima.

Nagasaki’s fate is also ignored, save three or four brief and rather forced mentions in the final hour of the picture. But Nolan’s most significant failing lies in not confronting—and in some ways sustaining—the popular narrative around the decision to drop the bombs, one that endures in government and media circles and among many historians, and is thereby reflected in public opinion polls.

That narrative holds that it was the detonation of the two bombs, and only that, which brought the Pacific war to an end. Simple cause-and-effect. The key scene in this regard in Nolan’s film, largely accurate, depicts the late-May 1945 meeting of the Interim Committee, President Harry Truman’s top advisory panel on the matter. One or two advisers question the necessity of deploying such a terrible weapon against Japanese cities, but their doubts are silenced by an officer who insists the Japanese won’t surrender otherwise, and a host of American soldiers will then have to die storming the country’s beaches. The panel is reminded of how savagely the Japanese have fought to the last man in other circumstances.

When one attendee suggests using a “demonstration” blast instead to compel a Japanese surrender, Oppenheimer shoots this down. The Japanese will only give up, he argues, if they see the full, city-destroying effects of the bomb. And suppose it’s a dud? Or, forewarned by a demonstration blast, the Japanese are able to track and shoot down the bomber shuttling the real thing? Another panelist remarks that he might very well be in that plane. End of argument.

These arguments form the core of the story that has held sway since 1945, despite new evidence and compelling arguments raised by numerous historians. From Nolan’s movie, you’d never know that many historians today believe that if Truman had waited just three days after Hiroshima for the Soviets to enter the war as the US insisted, the Japanese would likely have surrendered in about the same time frame. (That bloody invasion cited in the movie was still more than three months off.) Truman himself wrote in his diary in mid-July, after the Trinity test, that when the Soviet Union declared war it would mean “Fini Japs”—even without the bomb.

The Nagasaki bombing, three days after Hiroshima, is even more deeply questioned by experts. In real life, it was the death toll from that second bomb that got to Oppenheimer’s conscience—however ambivalent he remained about the bomb’s deployment more broadly.

Nolan channels Oppie’s regrets in the final hour of the film with an actual Oppenheimer quote noting that the bomb was used against “an essentially defeated” enemy. More possible regrets, in words and visions, follow.

This may result in some moral ambivalence among moviegoers. The problem is that most, I would guess, will ask, Why have regrets? The main takeaway, relayed with passion and never contradicted, is that the bomb prevented an invasion, saved countless US lives, and ended the war. Yes, many Japanese died, and the script eventually puts a number on it, but Nolan fails to point out that 85 percent were civilians. Oppenheimer’s ambiguous qualms—mainly about making bigger bombs after Hiroshima—do little to disrupt the powerful central narrative.

Even if Nolan refused to take sides in the historical debate, he should have at least included clear counter-arguments, especially since he never shows what happened at the receiving end of the Hiroshima bomb, beyond a few hazy seconds in one of Oppie’s visions.

Why does any of this matter? Nolan, who focuses (rightly so) more on 2023 than 1945, provides a clear, compelling, and important message about Oppenheimer’s legacy and the dangers posed by nuclear weapons today. Everyone should experience the movie. But his message is undermined by his failure to challenge America’s use of the bomb, beyond trying to make sense of Oppenheimer’s wildly conflicting emotions.

Yes, nuclear weapons must be limited and controlled, but the United States and most other nuclear nations embrace a “first-use” policy that allows for an atomic first strike in response to conventional attacks. So long as exceptions are made for using such weapons in times of war, their eventual deployment becomes all the more likely.

Documentary filmmaker Greg Mitchell is the author of The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and a dozen other books, including, Hiroshima in America and Atomic Cover-up.