In January 2020, Barbers Hill High School in Mont Belvieu, Texas, made national headlines after suspending a Black student over his dreadlocks, ordering DeAndre Arnold to cut them if he wanted to attend graduation. The incident partly inspired the CROWN Act, a state law that prohibits race-based hair discrimination in schools, housing, and workplaces. But on August 31, reportedly one day before the law was slated to go into effect, Barbers Hill High School disciplined another Black student, Darryl George, over his locs hairstyle. George’s parents are now suing Gov. Greg Abbott for failing to enforce the law.

The episodes at Barbers Hills High reflect a longstanding issue in the United States, particularly in schools where dress codes can discriminate against students. You saw it in the video of a New Jersey high school wrestler forced to cut his locs after a referee claimed that keeping them would forfeit the match. When a North Carolina charter school demanded that a young Indigenous boy cut his hair before returning to class after spring break. Such incidents, widely condemned as racist, have sparked laws similar to the CROWN Act around the country.

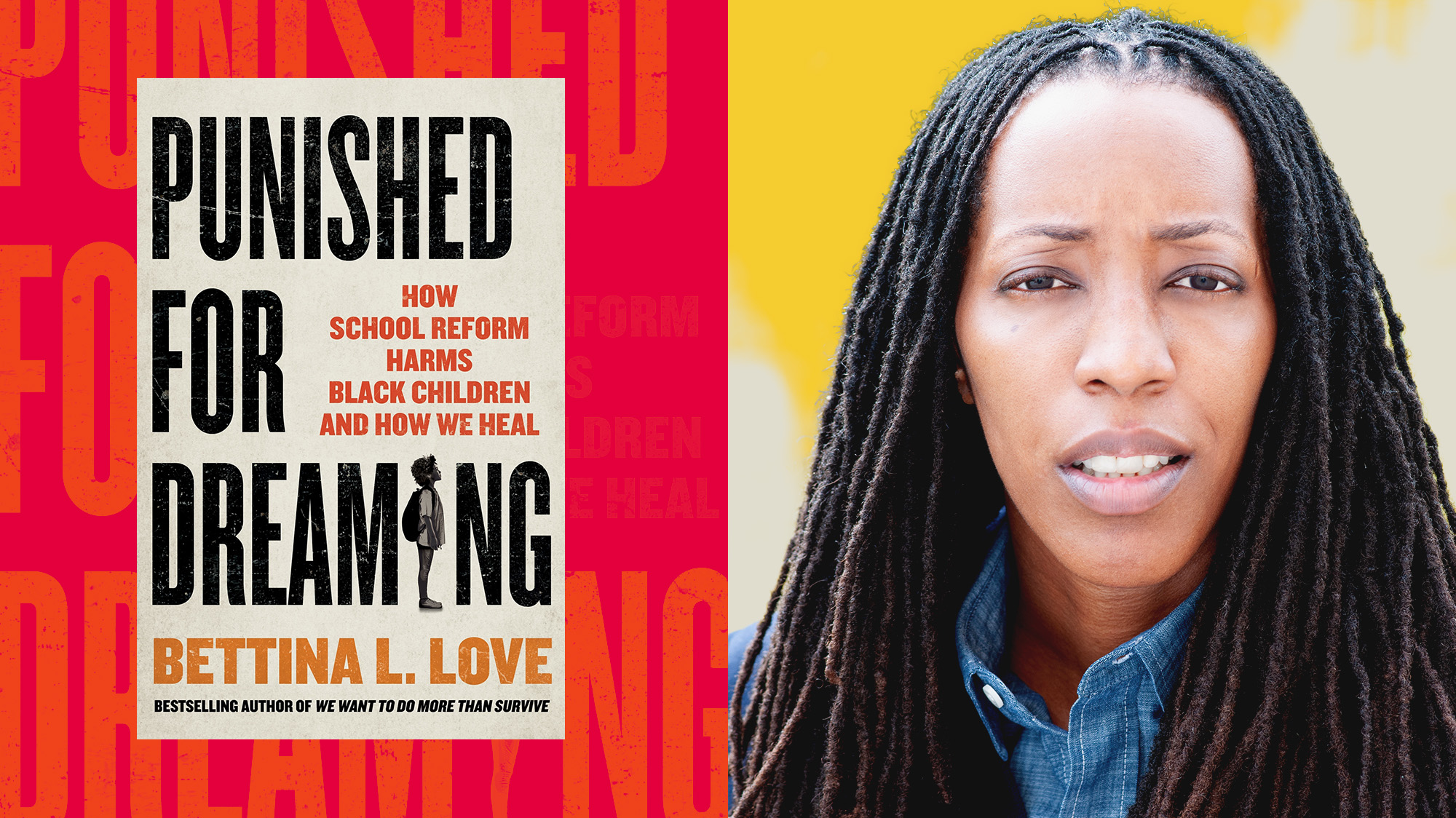

Despite these protections, school administrators still enforce policies that target non-white students. Mother Jones spoke with Dr. Bettina Love, a professor of education at Columbia University and author of Punished for Dreaming: How School Reform Harms Black Children and How We Heal, to learn more about how school systems in the United States codify policies that ultimately force students of color to assimilate to whiteness.

How did we end up with an education system that can suspend Black students for wearing natural hairstyles like locs?

It’s important to note this story isn’t just about hair. It’s about anti-Blackness. Black people’s hair is such an important symbol of our identity. It’s about who we are and how we express ourselves. It’s an easy signifier to go after but these suspension policies are about us as human beings. Sometimes when we think about racism, we just think about policy. What we miss is how the body is attacked. Our hair is one of the biggest reflections of our blackness and so it is always going to be under attack.

Your new book explores the politics that brought us to this point. How common is it for Black students to be policed and suspended for expressing themselves or their culture?

What I tried to do in the book is show how education reform shifted, particularly once [Ronald] Reagan took office, to be extremely anti-Black. There are a few entry points we can look at to understand how we got here. First, we have to start with the very pursuit of integration after Brown v. Board of Education which gutted Black education. Before Brown, we had Black teachers who understood Black culture. Fast forward to 1982 when Reagan declares a war on drugs, which is really a war on Black people.

By 1984, the Reagan administration comes out with another report called Chaos in the Classroom. It says certain children—they never have to say Black children, but we know who they are talking about—are unruly, disrespectful, and need to be policed. That’s when you start to see crime reform, which is tied to the idea that Black people are inherently criminal and violent, merge with school reform. Policing concepts, like broken windows theory and three strikes rules, become education policies. Labels like “thugs,” “crack babies,” and “superpredators” enter public consciousness. There was a united effort by politicians and the media to dispose of Black children through schooling.

Schools have always been hubs of political and cultural battles. But in recent years, conservative politicians and groups have upped the ante, targeting Black history and literature in schools. How have these attacks impacted Black students?

I want to be clear: This is how you create chaos and manufacture crisis. It is the same playbook they used in 1983 with “A Nation at Risk.” They are manufacturing crises so they can say that public education is no longer needed. These attacks are about much more than attacking Blackness. We are being used for a larger agenda: to privatize education.

But students are starting to educate themselves. They are turning to the internet and TikTok. They are saying, “Well if you say we can’t read this, we’ll find out what that book is about.” Young people are curious about why this is happening. They are walking out of school and protesting. They want to know why they’re being denied the chance to read and learn. I hope it’s making this generation more inquisitive because they will have to seek out new ways to make sense of what is happening. That said, this whole situation is infuriating. Black children shouldn’t have to struggle like this. And I want to be clear, this doesn’t just impact Black students. What’s happening right now impacts all students because Black history is American history. Keeping students ignorant is not how you have a flourishing, thoughtful caring democracy.

The district superintendent involved in George’s case defended the hair policy by claiming it taught students to “sacrifice” and “conform.” Can you talk about the realities of forced assimilation for students of color?

It is always important to ask whose culture we need to assimilate to. And the very idea that this student needs to learn to sacrifice while other folks get to have liberties, freedom, and choice is despicable. Why does he have to sacrifice? Where is his freedom? One of my favorite quotes is by Professor Lindsey Stewart and she says white folks believe Black lives are tragic without intervention. That superintendent clearly believes that. That without his rules and policies, this young man will not learn sacrifice. This is a lesson in double standards, not sacrifice. This is a form of killing a child’s spirit. Now that student has seen how racism works in this country and how policies can make him disposable.

Can you describe the cultural significance of natural hairstyles in Black communities? Why is it more than “just hair”?

When I hear these stories, it’s a little triggering for me because that could have been me. I have a very similar hairstyle to the young man who was suspended for two weeks. Natural hair defines who we are as Black people.

No shade to Black people who don’t wear their hair natural, but if you do, you’re making a commitment to put your Blackness on display. I wear my hair natural for a few reasons. One, it’s healthier for my hair and healthier for my body. Two, I am reinforcing that my Blackness is beautiful through my hair. Natural hair is a signifier of my commitment to the beauty of Blackness.

Beyond cultural significance, how does Black joy play a role in self-expression and why is it important that Black children get the opportunity to express themselves?

So, there’s a definition of self-love and it comes from Lizzie Stewart again. And she says that the real essence of Black joy is where whiteness doesn’t exist. And for those moments and for those seconds, you are free. That is the Black joy that I want our children to be striving for. There are teachers who can facilitate that kind of joy. But schools as a whole are not doing that work. Most teachers are white women. How would they know how to facilitate Black joy?

Why is legislation like the CROWN Act necessary? Are there more effective ways to protect Black students in school?

The fact that we even have to have a CROWN Act says so much about this country. It is unbelievable that we are fighting in 2023 for Black folks to be able to wear their hair the way they want to.

But we need a few things. Number one is the hiring of Black educators. There’s good data out of American University that says if you are a Black student from a low-income family and you have two Black teachers in elementary school, the likelihood that you will graduate increases by 32 percent. It matters to be able to have a teacher who looks like you. We need a true recruitment of Black teachers. We also need to mobilize Black parents. We have a few powerful people changing the course of public education in this country and we need parents —all parents—to understand what’s happening.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.