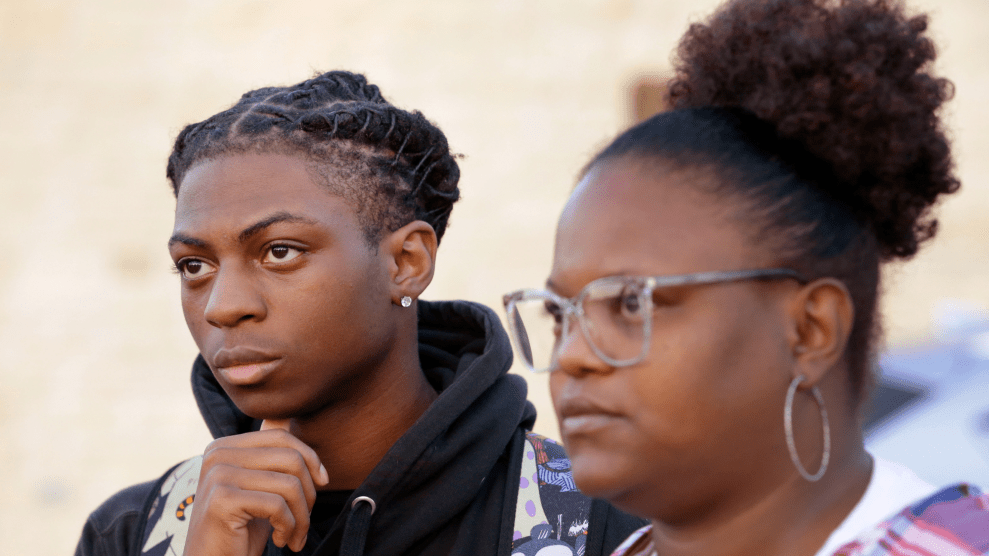

Michael Wyke/AP

Last week, Barbers High School in Mont Belvieu, Texas, after administering more than 40 days of in-school suspension to 18-year-old Darryl George for the length of his dreadlocks, removed him from classes and enrolled him in a disciplinary program. Since October 12, George, who has filed a lawsuit against the district and state authorities, has been attending the Eagle Positive Intervention Center, or EPIC, an “alternative school” whose corporate partners include fast food chain Sonic, Dick’s Sporting Goods, and Amazon.

Among the several questions on my mind, one really sticks out: How is penalizing this teen supposed to further his education? According to racial justice and education advocates alike, it doesn’t, and could very well be hurting his grades and future as a student—just one example of a much larger issue affecting many Black youth today.

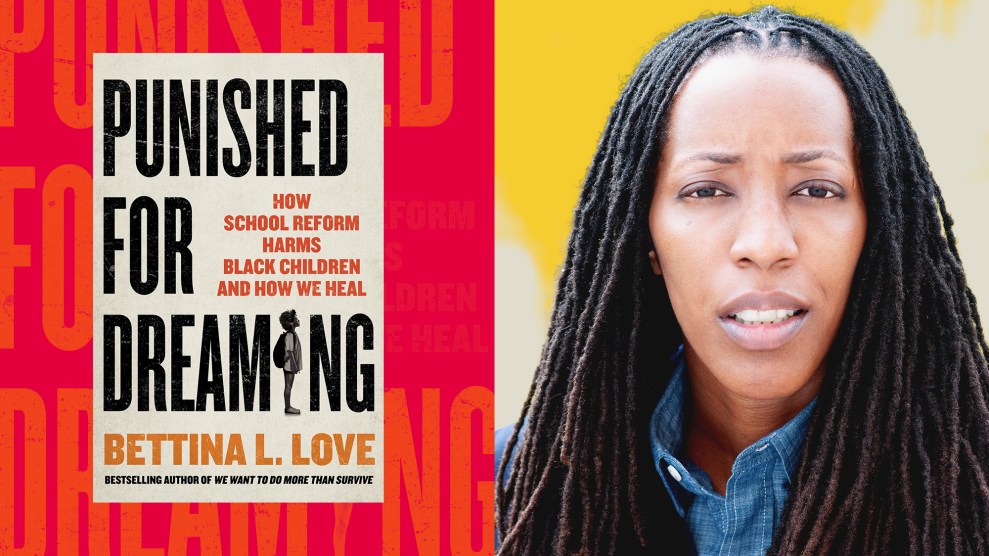

“Punishing him for his hair does not at all help him,” Columbia University education professor Bettina Love told me. “At the end of the day, how is this young man supposed to feel about his school? How is he supposed to feel that this place is safe for him and values him?”

As my colleague nia t. evans and I explored in a recent interview with Love, discriminatory policies like those at Barbers High School are not designed to help marginalized students thrive. They instead strong-arm them into conforming with whiteness. But the baked-in discrimination of these rules isn’t where bias against Black students ends. Ultimately, these targeted punishments can have devastating effects on Black students’ academic performance and cause long-term damage to their relationships with education.

A 2021 University of Pittsburgh study, promoted by the American Psychological Association, found that not only were Black students cited more often for minor infractions, like dress code violations, than their white counterparts, but that they were more likely to report “an unfavorable school climate” the following year, resulting in lower grades. Another study in the journal Psychological Science found that students who experience in-school punishment are more likely to drop out and to face incarceration.

“We do not need to police children’s bodies. This is school, where children should be able to express themselves, which includes clothing and hair,” said Love. “What do these policies have to do with improving reading scores or math scores? Not a damn thing.”

When it comes to improving the treatment of Black students in the country’s school system, there are several places to start. As Love previously stated:

“Number one is the hiring of Black educators. There’s good data out of American University that says if you are a Black student from a low-income family and you have two Black teachers in elementary school, the likelihood that you will graduate increases by 32 percent. It matters to be able to have a teacher who looks like you. We need a true recruitment of Black teachers. We also need to mobilize Black parents. We have a few powerful people changing the course of public education in this country and we need parents—all parents—to understand what’s happening.”

In the meantime, she advises marginalized students facing intolerance in their schools to reach out to trusted adults and their own peers for reassurance and support as they fight against racist systems. But, the responsibility falls on school districts to eliminate discriminatory policies in the first place.

“A child should not feel like the place where they are mandated to go doesn’t value them or their culture,” said Love. “You can’t learn like that and you shouldn’t have to.”