Mother Jones; Mark Clennon

In March 1911, the segregated Crownsville asylum opened outside Baltimore, Maryland, admitting only Black patients. It was the first to house Black people in the state, but when they arrived, their main role wasn’t to get support—it was to build the asylum. The combination of ableism and sanism—harmful beliefs about the nature and treatment of mental illness—with anti-Black racism in the Jim Crow South all but ensured that Black patients were treated worse than white ones held in other asylums throughout the state.

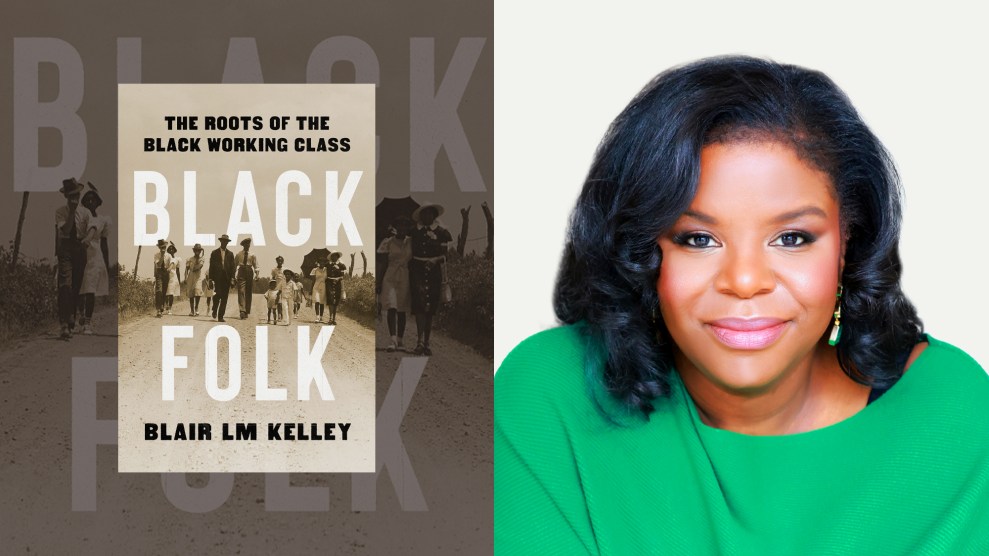

In Madness, journalist Antonia Hylton details the institution’s treatment of Black patients—some placed there due to being orphans, seeking better treatment at work, or, in the case of one British man, because some white people found his accent to be suspect. Hylton discovered Crownsville as a university student, wanting to learn more about the history and experiences of people of color in mental health systems.

When she began her research, Hylton knew that Black patients had been mistreated, but found that many records the state of Maryland was supposed to keep had been destroyed or damaged. So she weaved together what archives she could find—like reporting from Black newspapers at the time—and interviewed surviving ex-employees who remembered Crownsville before reforms started to take place.

“Starting to learn more about Crownsville and sharing my research with my own family,” Hylton told me, “opened up doors and started conversations”—including about her father’s cousin Maynard, who experienced auditory hallucinations and was killed by an Alabama police officer in 1976.

Nearly two decades after Crownsville shut down for good in 2004, Hylton talked to Mother Jones about its history, how Black people with mental illnesses have been mistreated, and why it’s crucial to end the demonization and criminalization of marginalized people who live with mental health conditions today.

For readers who aren’t familiar with the history you cover, could you talk about psychiatry and race in the Jim Crow South?

Everything about psychiatry, in that period, was infected with the thinking, the structures, and the attitudes of that time. For decades, white doctors and white thinkers in our country were writing, debating, and discussing what they observed to be large numbers and huge spikes of mentally unwell Black people. Many white doctors at the time, including some discussed in the book, thought Black people’s mental suffering was distinct from white people’s, that Black people were unable to handle freedom, so emancipation had in some way been a mistake, and so they needed to be in a separate facility.

What was the role of Black labor at Crownsville?

Crownsville Hospital could not have existed—would not have functioned and survived—without its patients’ labor. It’s the only hospital I found that forced its own patients to build it from the ground up. It is important that people understand that they were not just carrying some sandbags [or] helping out making sandwiches. They were doing backbreaking labor: clearing trees and roads, moving railways, establishing foundations, pouring cement, working alongside electricians. They also forced young boys with physical disabilities to take part in the labor they described in “lunacy reports,” written by officials in Maryland. No patient was exempt from having to do work.

The reality is that, in that period, every asylum had some patient labor—white asylums included. They were supposed to be modeled on European industrial therapy: the idea is you’re learning a trade that is going to make you marketable for a job, when you eventually recover. Those programs were themselves often very abusive to patients of all backgrounds. But there really was no pretense, in the case of Crownsville, that this kind of labor was going to lead you to a job.

It took decades for Crownsville to hire Black medical staff. Did it become harder for white staff to facilitate or hide abuse?

According to the dozens of Black nurses and doctors that I’ve spoken to over the last 10 years, the short answer is yes. They were watching constantly. Often those Black employees found themselves in a position where they were going above and beyond and using their own resources. One woman described bringing in strings so that she could help patients whose pants had repeatedly been falling down. It’s those very small and simple acts of kindness that they felt really no other choice [than] to do so that they could just feel even half-okay functioning at a workplace like this every day.

Some of the [first Black] employees, who are now in their 90s, described to me this period in the 1950s [of] just a few Black employees. It was really traumatizing for them. The first thing they share with me is often the smell—for so long, the white staff had refused to bathe [patients], feces all over the place. They would allow people to just sit or sleep on floors, on benches, sleep on open porches, not even getting the dignity of simply a mattress or blanket.

Even within Maryland’s Black communities, families had to fight to bring attention to how Black patients were treated in Crownsville, as you touch on in your book, including with the NAACP. What does that tell us about the stigma around mental illness, then and now?

When you look at organizations like the NAACP, and some of these other professional groups that were fighting for the advancement of civil rights of Black communities, at times they felt a pressure to present—in a word that’s very commonly used in the Black community—in a respectable way. But there are these wonderful people who come along the way, including Black reporters, and a couple of doctors and lawyers who find their way inside the asylum and try to publish and publicize what they find. Without those few people, in the bigger picture, you see a society that was comfortable discarding people.

I think a lot of families are still allowing loved ones who are suffering to slowly disappear, even if it’s not that they’re disappearing in massive asylums. One of the reasons I wrote about my family and my own journey, alongside the reporting and the research and the space, is because I felt like I had this obligation to reckon with what some of these forces had done [to] me and my loved ones, and then to resurrect my dad’s cousin Maynard: I am not gonna let you be in the shadows anymore. I’m not gonna let you retreat to a footnote of our family history. You’re gonna be out front.

Elsie Lacks, the daughter of Henrietta Lacks, a Black cancer patient whose cells were used without her consent for what is now considered to be crucial research, was a patient at Crownsville. What were the parallels between their experiences?

While her mother is going through these cancer treatments—and unbeknownst to Henrietta, being used in this way—her daughter is at this place that is ostensibly supposed to care for her and help her gain some skills. Instead, [Elsie] becomes this tool of experimentation. Elsie becomes part of a group of about 100 patients who are diagnosed with epilepsy and used for this invasive procedure in the skull, where helium is pumped in so that they can get a good look at the brain.

According to reports, Elsie really suffered towards the end of her life, and was vomiting almost constantly and in extreme pain after being subjected to that. Not only is it in parallel to her mom’s [experience], but it makes this broader point about the way in which Black people and their bodies have contributed to science. There’s no credit, there’s no acknowledgment, and the best we can do is resurrect some of the story of their life now.

A lot of people weren’t paying attention to Crownsville’s treatment of people with mental illness. What similar situations do you see today in terms of medical racism—and in terms of police brutality towards Black people with mental illnesses?

It’s part of the reason why I was inspired to write about Jordan Neely in the epilogue. I wanted to give them a voice and weave their perspectives into my own process of grappling with his death here in the city [of New York City]. Part of the concern of the book is, To what extent are we doing better? How much have we actually changed? And is the system that we have now changing? Is it serving anyone—but in particular, is it serving people of color? I think that many of the people I’ve met along the way in this recording, and in my story, would say that the answer is no.

You may find yourself houseless and fighting for yourself, and you’re surviving on the streets—you are more likely to to interact with the criminal justice system than you are to be truly connected to care. So often as a reporter, I meet people who tell me that the more violence they’ve been subjected to, the more they have struggled in their lives, the more they seem to cry out for help, the less empathy they receive. I wonder to what extent we might be able to imagine something better.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.