This story is a collaboration with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and Magnum Foundation. We asked photographers to show us the paradox of today’s labor movement. Even as the popularity of unions has grown over the last decade, actual membership has continued to decline. Can new enthusiasm revitalize American labor?

Jump to all the photo projects

The American public seems to have emerged from the initial jolt of the pandemic with a newfound clarity familiar to survivors of catastrophes. Many people experienced an evaporation of the things that lent their lives the illusion of stability. Jobs disappeared and the social safety net’s holes loomed large. For scores of working people, it was—though they might not use this term—a radicalizing experience. Millions suddenly confronted the fact that if we didn’t protect ourselves, nobody else would. “I don’t really know if any amount of money would make working in this environment and being exposed to this level of risk feel worth it,” one grocery worker said early in the pandemic. For “essential” workers, it became clear that the work and the risk were a package deal.

This realization supercharged public interest in organized labor, bolstering a surge of support for union activity, which had already been growing slowly since the Great Recession in 2009. Polls show that public approval of labor unions is now at its highest point since 1965. This is unsurprising. Since the start of the Reagan era, wages for average workers have stagnated, astounding wealth has flowed to a tiny percentage of society, and the resulting rise in economic inequality has destabilized our political landscape. When this slow but steady erosion of the American Dream met the shock of Covid, it became all but impossible to avoid the conclusion that “Organize or Die” could be a literal slogan.

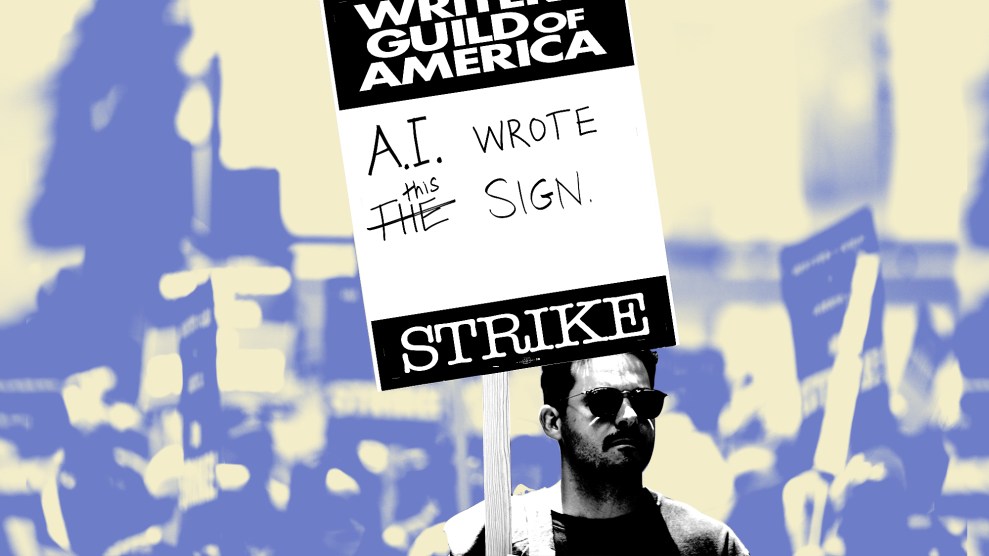

In 2020, we saw the launch of the (ultimately unsuccessful) union drive at the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama—at that point the most serious organizing effort against the Bezos empire. The addition of Covid’s burden to the weight of algorithmically driven warehouse work was the tipping point for fed-up workers unwilling to risk their lives for $15.50 an hour. That effort was followed in 2021 by a series of victories: a successful union vote at the Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, the launch of the still-growing Starbucks union organizing campaign, and a mini-wave of strikes dubbed “Striketober.” The drumbeat grew louder in 2023, with major strikes in Hollywood and at the Big Three automakers. In September, Joe Biden spoke at a picket line in support of United Auto Workers, the first sitting president in history to do so. It was clear that something was happening.

But what, exactly? The long-overdue return of unions to the spotlight is not the sea change that it can appear to be. In the middle of the 20th century, when American unions were at peak membership, about one in three workers was in a union. By 1980, the number had fallen to one in five, and by 2005, one in eight. This unrelenting decline in union density—the percentage of workers who are members—is the biggest problem facing organized labor. And since strong unions tend to improve wages and conditions even for nonunion employees, and make politics more worker-friendly, low union density is a problem for the entire working class and, more broadly, anyone with a job. Each success is meaningful to individual workers. But the wins do not add up to a transformative movement unless they can reverse decades of decline—which has not yet happened.

In 2022, even as the popularity of unions hit a generational high, union density fell to 10.1 percent, the lowest on record. The inability to channel all this excitement, during the most pro-union administration of most voters’ lifetimes, into an economy wide barrage of large-scale organizing drives, should put a lump in the throat of anyone who cares about the class war. The traditional analysis of union decline cites two main causes. The first is the devastating effects of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act—which restricted how unions could strike; outlawed “closed shops”; and enabled states to pass “right to work” laws, which under the guise of worker freedom allow a member of a unionized workplace to opt out of paying fees. The second cause is corporate America’s decades-long project to perfect its union-busting tactics.

But you can’t just chalk up organized labor’s woes to the old saws of union-busting businesses and hostile laws. They also reflect the atrophied state of labor’s institutions, a lack of adequate organizing infrastructure and budgets, and, in many cases, an attitude of resignation that decades of decline inflicted on some union leaders who should, right now, be rushing to capitalize on the favorable conditions.

From the very earliest days of worker organizing, there have been two fundamental competing visions. One side, rooted in the craft guilds of skilled workers, says that unions exist to take care of their members. The other, rooted in the mass industrial unions, argues that the labor movement exists to serve the wider purpose of helping all workers. It is the first philosophy, that of the self-declared realists, that has historically dominated the union world. The most vivid example of this divide came in 1938, when crusading United Mine Workers of America leader John L. Lewis, dissatisfied with the staid attitude of the American Federation of Labor, became the first leader of the more radical Congress of Industrial Organizations, which successfully pursued broad organizing in steel, auto, rubber, and other fields before merging back with the larger, more conservative AFL in 1955. While the first camp looks at a group of workers and decides whether it is in a union’s interests to organize them, the second camp looks at the unions and wonders why they are failing in their responsibility to organize everyone. It is the former outlook that prevailed.

Today, surrounded by centibillionaires and trillion-dollar corporations and a depressing private sector union density of 6 percent, we can safely look back on the past half-century and say: Well, that didn’t work.

Declaring that organized labor is poised for a resurrection is a dangerous prediction. It has been wrong often. Yet now, things may just be lined up. The failure of the union world’s narrow-mindedness in the face of the rising inequality and corporate power is running up against a general public that is tired, pissed off, and ready for action. To put it plainly: Work sucks, and people know it. Inequality taunts us from above, and crappy jobs taunt us from below. Unions are the path to salvation and, incredibly, people seem to have realized it. Now we find out whether the labor movement can meet the challenge of turning rage into rebirth.

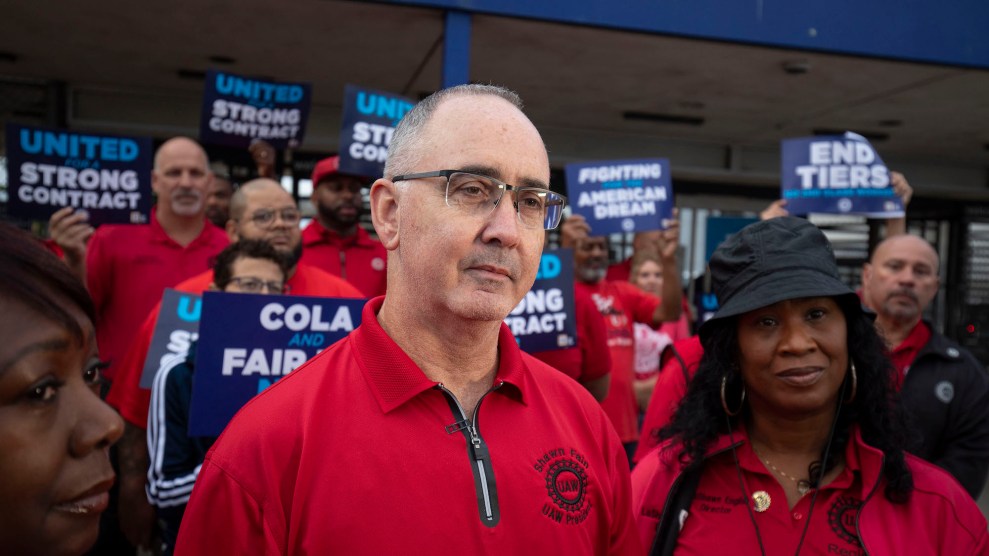

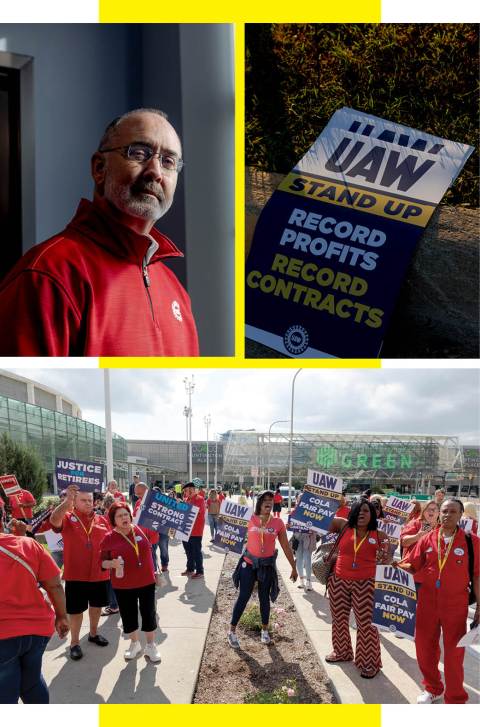

Last year, we asked photographers to document this knotty moment for American labor. Their projects show both new organizing and the reinvigoration of old institutions. In March 2023, reform-minded Shawn Fain was elected president of the UAW by a margin of less than 1 percent. He proceeded to don an “EAT THE RICH” T-shirt and lead the boldest strike in the union’s history, shutting down all of the Big Three automakers and winning record wage gains for workers. Instead of resting on these victories, he announced an aggressive plan to organize nearly 150,000 nonunion autoworkers across the country.

In less than a year, Fain proved that unions already possess the most potent ingredient necessary for their rejuvenation: ambition. Images of the UAW on the frontlines empowered workers beyond any individual contract fight. In Los Angeles, something similar happened: So many workers went on strike last year—hotel workers, public school workers, and Hollywood actors alike—that the entire city seemed to morph into a living demonstration of the way unions lend power to everyone, from janitors to movie stars. Every labor victory serves as a giant billboard to nonunion workers: Organize, and you can have this too.

But there is much ground to make up. Horse-trading to pass foundational labor laws has left some of the most exploited classes of workers behind. In 1935, the Wagner Act, which gave private sector workers the right to unionize, explicitly excluded farmworkers and domestic workers, among others. And decades of “War on Crime” politics have created a vast pool of formerly incarcerated people who find themselves excluded from stable employment, easy prey for bad bosses and low wages. (If the labor movement won’t take on the task of helping them, who will?)

After decades of globalization, America’s industrial jobs have been lost. Millions of service and retail workers—for many, the only jobs left in the wake of neoliberalism’s offshoring—have thus far been nearly impossible to unionize. This is particularly true in the South. If unions cannot find a way to effectively organize the retail chains that dominate American commerce, it will not just be bad news for all of those underpaid, disrespected workers; it will be an ominous sign that businesses can leverage global changes in the economy to purge unions and keep them out indefinitely.

The invigorating moment we are now living through has the potential to propel unions back into the center of American life. Fully capturing this burst of energy is necessary if organized labor ever wants to fulfill its larger purpose: restoring the balance of power between capital and humanity. Beyond material gains, people want to change what jobs are—to transform these weird, necessary evils into a tolerable part of our lives. Without scrutiny, the workplace, where we spend many of our waking hours, can become a dark and dictatorial haunt. The labor movement seeks to shine a light in these spaces. “Don’t quit, organize,” goes the rallying cry. That has, for most of our lifetimes, been a difficult ask. But things change.

The zeitgeist is, for now, in our favor. These images capture the spirit of those trying to seize it.

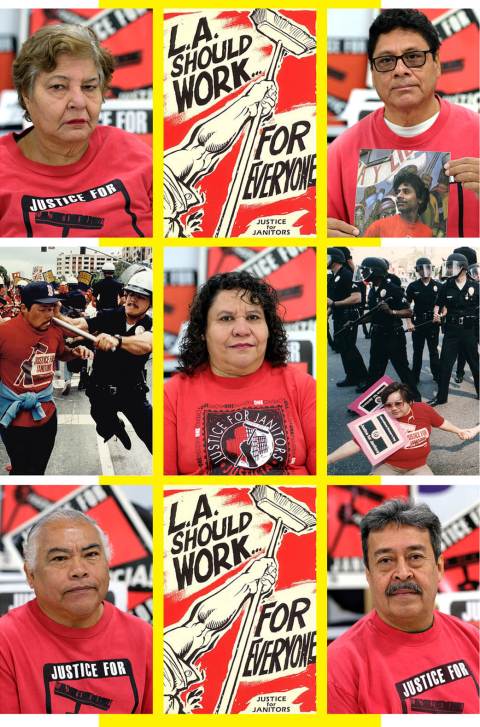

City on Strike

By Sara Terry

In 2023, Los Angeles experienced an explosion of strikes across almost every sector of the economy. This project looks at how the city’s Justice for Janitors organizing in 1990—a historic and unexpected victory—laid the groundwork for organizing today. View the full project here.

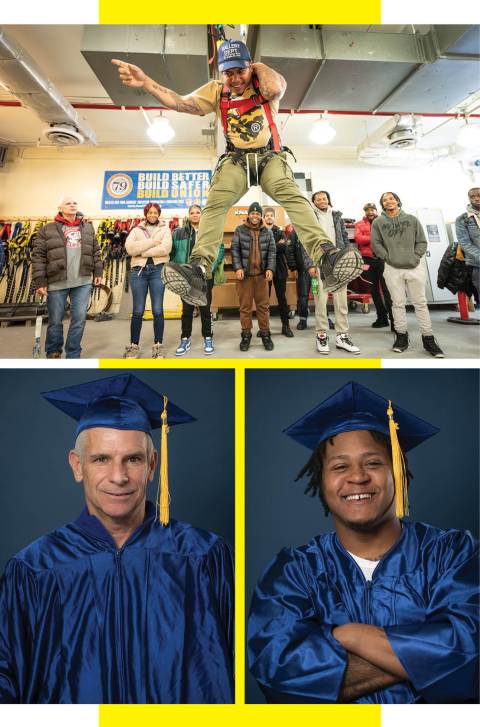

Another Chance

By Jeff Rae

In New York City, low-income workers, especially those recently released from prison, are often recruited to work for so-called body shops—low-wage construction firms with few labor protections. Jeff Rae documents a program that offers an alternative: a paid pathway to apprenticeships that can lead to union jobs. View the full project here.

The Almighty Dollar

By Rita Harper

Working at a dollar store is often low-paid and dangerous—according to the Gun Violence Archive, more than 660 shootings have occurred in such stores since 2014. In the South, dollar store workers are organizing to improve their lot. Rita Harper photographed the fight by Step Up Louisiana to organize retail workers to push for better conditions. As blue-collar workers continue to migrate from the factory floor to the retail aisle, fights like this could determine whether a working-class job can still provide a decent life in America. View the full project here.

Eat the Rich

By Sylvia Jarrus

Last year, under the leadership of Shawn Fain, the United Auto Workers conducted a historic 46-day strike that harkened back to the union’s militant roots. Sylvia Jarrus’ photos take us to the front lines to show the impacts of one of the most consequential labor fights of the 21st century. The new contract, Fain promised in his post-victory speech, is no less than “a turning point in the class war.” View the full project here.

Lessons in Class War

By Octavio Jones

As Gov. Ron DeSantis battles to reshape education in the state, the culture war is part of a class war: Unions are on the front lines of the fight over what educators can or (more often) cannot do. View the full project here.

Home Work

By Chloe Aftel

Domestic workers perform grueling work with few protections. Infamously, the group was excluded from the labor agenda during the New Deal. And, since then, workers have had to fight to catch up to standards enshrined for others in the law. Such care work can be hard to see and even questioned as work at all. Chloe Aftel’s photos highlight the day-to-day demands of the workers caring for those who struggle to care for themselves. View the full project here.