David Carson/AP

This story was originally published by Capital & Main.

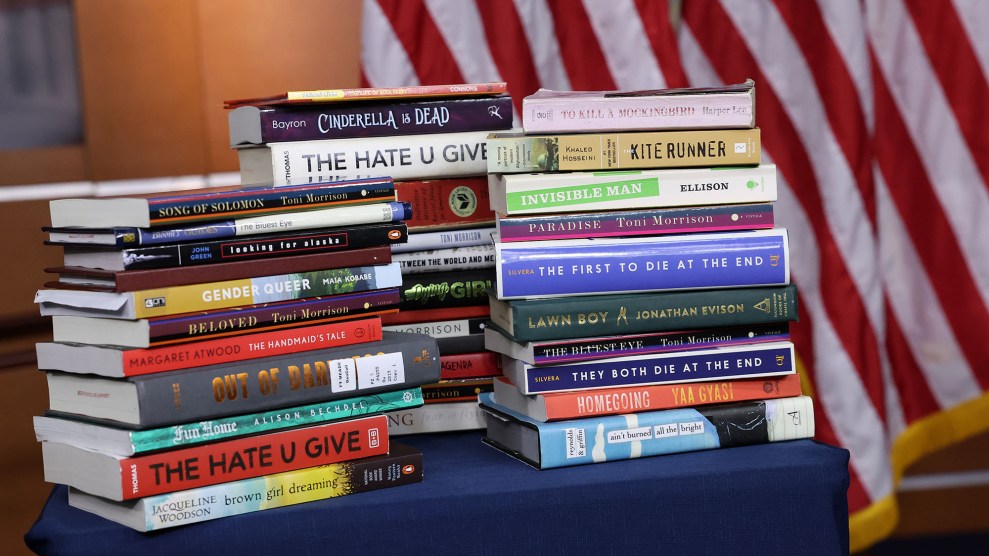

The protests and student walkouts have stopped as an uneasy calm settles over St. Charles County, Missouri, after the community’s all-white school board threatened to eliminate both a Black history class and Black literature class, saying the curriculum contained elements of critical race theory.

As community outrage drew national media attention, the board retreated and said the curriculum would be reviewed, rewritten to be “largely political neutral” and brought back in time for the next school year.

While that has tempered public indignation, for people like Miranda Bell, a Black mother of two students in the Francis Howell School District, there’s a nagging sense that the community has no sincere interest in teaching the honest history of people like her.

“Every day when they walk out the door, I don’t know if they’re safe, because I don’t know,” she said of her school-aged children. “But I do know they need to know who they are.”

The decision to drop the Black history and literature electives, which came on a 5-2 vote before Christmas, followed the board’s decision last July to allow the district’s anti-racism resolution, adopted in August 2020, to expire and to order schools to remove framed copies of the resolution from classroom walls.

Through the resolution the school board pledged that the district would “speak firmly against any racism, discrimination, and senseless violence against people regardless of race, ethnicity, nationality, immigration status, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, or ability.”

In 2022-23, five new, far-right members of the school board were elected.

The newly constituted board promised to draft a new resolution, but—more than eight months later—that still hasn’t happened.

Some in this St. Louis suburb say they find it hard to convey how thoroughly the school board has upended the district’s hard-won advances in dignifying Black humanity. Both the resolution and the courses grew from the community’s response to the 2020 police murder of George Floyd. Nearby Ferguson, Missouri, where 18-year-old Mike Brown was fatally shot by police in 2014, is considered the birthplace of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Adopting the resolution was a proud moment,” Bell said. “Very proud.”

Offering Black history and literature electives for the first time was an extension of that moment, she said.

She recalled that thousands of district residents, Black and white alike, marched in the streets and grieved together following Floyd’s murder. But now she wonders if that sense of togetherness, and the hope it afforded Black parents, whose children make up less than 8% of the Francis Howell School District student body, has dissipated.

“I find myself doing a lot of coping, spiritually, to survive,” she said.

Bell is not alone. Local policy advocate Heather Fleming formed the Missouri Equity Education Partnership (MEEP) in 2021. Her aim was to organize chapters in the state’s 554 school districts to battle those attempting to stoke the far-right school culture wars that have resulted in bans on critical race theory and anti-racism efforts and other policy changes across the country.

Fleming, a Black woman whose children attend school in the Francis Howell School District, told Capital & Main that the days of paying little attention to school boards “because we just depend that folks who run for school boards want to do what’s best for kids” are absolutely over.

“They’re telling our students to just ‘shut up and dribble,’” Fleming said. “They’re telling our kids, ‘You’ll never be human enough for us to treat you like equals.’”

She thinks the board’s entire approach to Black history rings false.

“They don’t want to teach Black history,” she said. “What they want is to change the white history of Black events.”

Randy Cook Jr., the school board’s vice president, told the Associated Press that the canceled courses appeared to be tilted toward activism.

“I do not object to teaching black history and black literature; but I do object to teaching black history and black literature through a social justice framework,” Cook wrote in an email to the Associated Press. “I do not believe it is the public school’s responsibility to teach social justice and activism.”

With these two salvos, the board has opened a racialized local front in the national culture wars. It’s directed by a local right-wing PAC that’s funding, running and electing candidates, but it copycats down to its website template, verbiage and policy playbook those of similar efforts in other states, according to local organizers.

As the curriculum was being rewritten, a community meeting was held on Feb. 5. According to local reporting, the Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Standards, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, were dropped from both courses with little impact on the literature course. But revisions to the history course changed the focus from analytical to factual and removed entire sections on “how laws and economic policies affected Black wealth,” and on “what historical and modern-day struggles exist for Black people working toward equity.” The proposed revisions led the school board’s Cook to pronounce that the history course as rewritten “has promise.”

Francis Howell School District board president Adam Bertrand did not respond to Capital & Main’s request for an update on the status of the anti-racism resolution. Superintendent Kenneth Roumpos did not respond to a request for information on whether individual teaching plans will be subject to any new levels of scrutiny.

Zebrina Looney, president of the NAACP chapter for St. Charles County, who has lived her entire 45 years in the area, told Capital & Main she worries about the divide between the Black community and the current school board.

“We’re taking a deep downward fall. I sometimes wonder if people generally understand the severity of what is going on,” Looney said.

When the anti-racism resolution was allowed to expire, she warned that it was “only the beginning for what this new board is set out to do.” Now, even with the concessions, she doubts the board is satisfied.

“I don’t think this is the last we will see from the board in this manner,” Looney said.

Black schoolchildren in the U.S. predominantly receive their education in public schools, where instruction dealing with racism is often under attack. In 2019 only about 6% of Black schoolchildren in the U.S. attended private schools, where they might encounter curricula that deal more openly with the country’s racist past.

For Lauren Chance, an 18-year-old senior who helped lead a student walkout on Jan. 18 in protest of the curriculum cancellation, the board’s assault on Black studies prompted a new clarity on her schooling.

“I’ve had teachers who value me and care about my learning, but as a whole, I do not feel that my education has been valued,” the young Black woman told Capital & Main. “In general, I don’t feel they’ve prepared me for what’s next.”

Chance, who took the embattled history course, thinks Black history should be required for all high school students because of the more realistic picture it provides of America’s story.

“Most students know nothing about their history,” said Chance. “We know the surface-level things and, even then, they still try to water those things down. But we do not really know our history.”

The revised Black history and Black literature curricula were formally approved by the board on March 21, but for Fleming, the policy advocate, it’s hardly cause for celebration.

“These rewritten courses have been approved by the board, but at what cost to our students, our teachers and the subject itself?” she asked. “Whitewashed history that disallows critical examination of the events, people and laws that have informed the Black experience in America does a disservice to all of our students.”