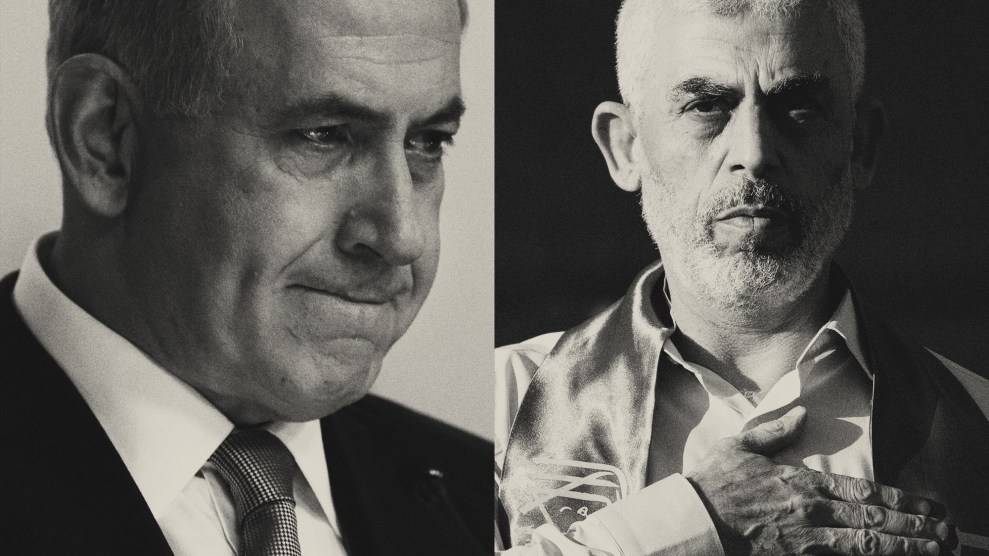

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Yahya SinwarMother Jones; Gali Tibbon/AP; John Minchillo/AP

Update, November 21: The ICC issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, alleging they “each bear criminal responsibility” for using starvation as a weapon of war as well as “murder, persecution, and other inhumane acts.” Israeli officials denied and condemned the charges. Hamas reportedly said the warrants against Netanyahu and Gallant set an “important historical precedent.” The ICC also issued an arrest warrant for Hamas commander Mohammed Diab Ibrahim Al-Masri, who was reportedly killed in July, on charges of murder, extermination, torture, rape, and taking hostages, among other crimes. The ICC said it had sought arrest warrants for two other Hamas commanders, Yahya Sinwar and Ismail Haniyeh, but withdrew them after confirmation of their deaths.

On May 20, International Criminal Court Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan announced he was seeking arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, and three Hamas leaders—Yahya Sinwar, Mohammed Diab Ibrahim Al-Masri, and Ismail Haniyeh—for alleged war crimes.

If a panel of three ICC judges approve the warrants, Netanyhau and Gallant could face charges for crimes against humanity, including the starvation of civilians. The Hamas leaders could face charges including murder, taking hostages, and torture, related to actions during and following the October 7 attacks that resulted in the deaths of approximately 1,200 Israelis and the kidnapping of more than 250 hostages, including some Americans.

Israel, Hamas, and the United States all condemned the news. President Biden called the announcement “outrageous.” Netanyahu said that in seeking the warrants, Khan had created a “twisted and false moral equivalence between the leaders of Israel and the henchmen of Hamas” and that the ICC was denying Israel’s right to self-defense. Hamas said in a statement the ICC announcement “equates the victim with the executioner.”

Khan refuted the idea that anyone was being unfairly targeted, telling CNN in an exclusive interview announcing the news that “this is not a witch hunt.”

“Nobody is above the law,” Khan added. “No people…have a get out of jail free card, have a free pass to say, ‘well the law doesn’t apply to us.’”

“This is not a witch hunt”: International Criminal Court Chief Prosecutor @KarimKhanQC appointed an independent panel of international legal experts to review the arrest warrant process. pic.twitter.com/ch2bZ5qa5U

— Christiane Amanpour (@amanpour) May 20, 2024

This afternoon, I called up David Bosco, executive associate dean and professor in the Department of International Studies at Indiana University Bloomington, to better understand the significance and ramifications of the news from the ICC. Bosco is the author of Rough Justice: The International Criminal Court in a World of Power Politics, and he has written about the relationship of the ICC to Israel and Palestine. We spoke about the meaning, and limits, of today’s announcement.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited.

I think when most people hear “arrest warrant,” they assume imminent prosecution. But that’s not quite the case here—can you explain what is actually happening right now?

The first important point is that all that’s happened right now is that the prosecutor has requested there be arrest warrants. Those have to be approved by a three-judge panel at the ICC. There’s no arrest warrant issued until those judges decide. And that’s a process that could take anywhere from a couple of weeks, to maybe even a couple of months.

And then if we do get arrest warrants—the ICC has no police force, no SWAT team that can go in and arrest people. So long as [the] people [prosecuted] are in Palestine or in Israel, it’s very unlikely that they would appear at the Hague.

Can you say more about the significance of this decision and what might have motivated the ICC prosecutor to make this announcement?

I think the prosecutor really realizes how controversial charges—particularly the charges against Israeli leaders—are going to be, and is trying to provide as much support, and indicate that it’s kind of not just his decision. So at the same time that he released his statement, there was almost an amicus brief from a group of international law experts supporting the prosecutor’s decision. That’s also something unusual; the prosecutor doesn’t usually have an expert panel backing him up on his decisions.

So what tangible impacts, if any, will these warrants have on the leaders’ daily lives?

I think it’s going to vary. For the leaders of Hamas, I don’t think there will be much impact, because either these people are in Gaza or some of them are traveling to other parts of the region, but not to countries that are ICC members.

Now for Netanyahu and Minister Gallant, it would be a different situation, because these are people who would hope to travel widely in representing Israel. If an arrest warrant ultimately is issued, that means that Netanyahu and Gallant would have to be very careful about where they travel, and traveling to an ICC member state will put them in significant risk, because ICC member states have a legal obligation to detain somebody who’s been charged by the court.

I saw the Israeli Foreign Minister has said he’s going to urge other foreign ministers not to comply with the warrants if they are issued. Is it likely that Israel could successfully exert pressure on ICC member states not to enforce this, or do you think the pressure of being a member state would compel relevant countries to comply?

We’ve already seen the United Kingdom—and I expect we’ll see more ICC member states—expressing opposition to this move. But there’s a big difference between saying, “we think the prosecutor got it wrong here,” and saying, “if an arrest warrant comes out, we’re not going to obey it.” That would be a much bigger step, and it would be very hard for many of these countries to take that step, because then you are really kind of breaching your obligations to the ICC. And many of the European countries were among the most supportive of creating the ICC, so I think that would be a very hard step for them.

Can you also provide a little background context on how it is that both the US and Israel are not member states of the ICC? Historically, why did that happen?

US policy is actually quite responsible for the creation of the ICC in a lot of ways. The US was the biggest supporter of the Nuremberg trials, it was the biggest supporter of the Yugoslav war trials, and the Rwanda Tribunal. And those things were ultimately what led to the creation of the ICC. So I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that you wouldn’t have the ICC in historical terms if it hadn’t been for US policy and US advocacy of international justice.

But the US has always had this kind of dual personality, where it really likes international law in some respects, but gets very nervous about accepting the jurisdiction of an international court. So the US balked back in the 1990s, when the ICC was being negotiated, and decided they did not want to ultimately be a part of the court once it became clear they weren’t going to have control of the court’s docket.

The US is just not comfortable with the court exercising jurisdiction over Americans, and Israel has felt very much the same way.

Both sides have alleged that it’s unfair for their leaders to be the subject of possible arrest warrants. From a symbolic perspective, is the ICC equating the leaders of Israel with the leaders of Hamas? What kind of signal is the ICC trying to send here?

I think what the ICC would say is, “we’re not in the business of setting up equivalencies.” There are moral and historical questions that weigh on how you see Hamas compared to how you see the government of Israel. And I think what the ICC would say is: That’s not our job; our job is to simply assess whether there are individuals who have committed war crimes or crimes against humanity—saying that Netanyahu may have committed war crimes is not the same thing as saying that Netanyahu is the same as the leader of Hamas. But inevitably, in the public discourse, people tend to say: “Whoa, the ICC is treating them all the same.”

If you think about World War II, for example, the Nuremberg trials, of course, focused on the crimes of Nazi Germany. But there were undoubtedly war crimes committed by the US and by the British during World War II. It so happened that the Nuremberg trials were set up so they could only consider the crimes of the Axis powers, but it’s probably not inaccurate to say that Franklin Roosevelt or Harry Truman committed war crimes. That doesn’t mean that they’re equivalent to Nazi leaders. So I think the ICC would say: That’s a judgment for historians, and ethicists and things—that’s not our job. Our job is to simply decide if there were crimes committed and investigate and prosecute those.

Israeli officials have continually tried to justify the strength of their response and the conditions in Gaza by saying they’re acting in self-defense. Do the charges that the Israeli leaders could face if these warrants are issued negate that argument?

No. Because basically in international law, there’s a divide between what’s referred to as jus ad bellum—that’s Latin for the right to use force. And how you use force, jus in bello. And those two are considered to be separate. So you can say that Israel was justified in using force in Gaza as a matter of self-defense. And that might be right from a legal perspective, when it comes to the right to use force. But that is a totally separate question from the question of what you do during the conduct of hostilities. And the same standards are supposed to apply to countries whether they are the aggressor or whether they’re the one defending. So whether they are just in their war or unjust they’re going to be subject to the same rules about how you use force.

You can’t just say: We’re acting in self-defense and therefore the rules don’t apply to us.

You can’t just say: We’re acting in self-defense and therefore the rules don’t apply to us.

Now, there are a bunch of really hard questions that prosecutors—if this ever reaches trial—are going to have to show, like, for example, “how much humanitarian aid are you obliged to let in during a conflict?” These are complicated questions where you’re balancing the military necessity versus the humanitarian impact.

But the short answer is: no, the fact that Israel might be acting in self-defense doesn’t absolve it from legal scrutiny.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that this could jeopardize ongoing efforts to reach a ceasefire deal. What’s your response to that, do you agree?

He’s pointing to a dilemma that has often been identified around international criminal justice, which is that there may be simultaneously the need to try to develop a pathway out of the conflict at a diplomatic level while there is a need to try to pursue justice and investigate crimes.

It’s hard to judge how accurate that is. There is a mechanism for trying to get out of that dilemma, if you really think it is a dilemma. The UN Security Council actually has the power to freeze an ICC investigation, because I think that people drafting the ICC statute didn’t realize that there might be a situation where we need to prioritize diplomacy over an investigation.

Just so I understand, is the thought that Israeli leaders would be unwilling to travel to neutral ground because they’re worried about the threat of arrest? How would the arrest warrant practically impact their decision about whether or not to engage in diplomacy?

That’s a very good question, and I don’t think it’s very clear. I think if there were to be negotiations, it would be in a place like Egypt or, you know, somewhere that’s not an ICC member state. So it really wouldn’t be an issue in terms of exposure to arrests—so I don’t think that’s the issue.

I think it’s more that the kind of outrage, honestly, that Israeli officials might feel, having been targeted in this way, that would make them less willing to engage in a diplomatic [manner]. But I don’t know that that’s right. I’m skeptical that that argument is necessarily the case here, that the justice process is necessarily getting in the way of diplomacy. And Israel, certainly, and the US, have an incentive to kind of exaggerate, I would say, that possibility.

How do you think this—the issuing of the warrants for Israeli leaders, and the US’s strong condemnations of it—impacts the perception of the US, considering that one of this country’s closest allies is being pursued by the ICC alongside the group responsible for carrying out the Oct. 7 attacks and Vladimir Putin, who was charged by the ICC for his role in the war in Ukraine?

I think the perception of the US on these issues is that the US engages in double standards when it comes to international justice. I think that perception is pretty baked into the view of the US, particularly on these issues, so I don’t think the fact that some US officials were very positive about the charges against Putin are now outraged by the charges against Israeli officials [is surprising]. I think that’ll just kind of reinforce and confirm that sense that ultimately, it all comes down to politics.

At this point, the ICC news is largely symbolic—there won’t be any imminent arrests or prosecutions—and the International Court of Justice case brought by South Africa alleging Israel is committing genocide in Gaza will take years to play out. So what purpose would you say these international institutions have when they can’t take any imminent action to address the humanitarian crisis that’s unfolding as we speak? Is there any reason for people who are concerned about the humanitarian crisis in Gaza to actually put faith in these institutions?

The short answer is I don’t think people should have a lot of faith in the ability of international judicial institutions to deal with a situation like this, or to really meaningfully impact a situation like this. Just like when we saw the arrest warrants against Putin and other Russian officials—within a few weeks, those were pretty much forgotten, and the war has continued, and there’s no sign it’s made any difference. So that is the reality: often times international law and international judicial institutions are going to have very little impact on these ongoing crises.

That’s not the same as saying they’re irrelevant. Because we have to also think about the very long-term, gradual impact on norms of behavior in the international system. And you have to think about what incentives are being created for other national leaders down the road. And that is hard to judge, but international law may not be as meaningless as it sometimes seems in the midst of a crisis like this.

The ICC is a very new creation. The idea that in the midst of an ongoing conflict, you’re having charges brought against officials for that conflict—this is a very new experiment. So that’s why, I think, we have to be careful about saying, “well, it’s not having an immediate impact, and therefore it’s irrelevant.” The international legal system is in a very gradual development toward what we hope, ultimately, will be a well-functioning system, that is really now a kind of embryonic system.

The way to be somewhat optimistic about it is the question is not: “Are these moves by the ICC going to change the Gaza conflict?” It is: “Are we making one step in the process that 20, 25 years down the road is really going to be impacting the way that leaders think?”

Do you have an answer to that question at this point?

I think it’s really kind of up in the air. I don’t think we know how this experiment is going to play out.