Kyle Mazza/NurPhoto/Zuma

The United States, as a rule, is not very good about pricing in negative costs, in part because the people responsible for those costs get very upset when you try. The federal gas tax—which is supposed to pay for infrastructure repairs necessitated by gas consumption—has not been raised in 31 years, so everyone else has to cover the balance. Gun violence costs in excess of $229 billion a year and the only people who aren’t on the hook for that are the people who make guns. The enormous societal costs of asthma and respiratory ailments are largely shouldered not by the people and corporations who poison the air, but invariably by kids who breathe it in. Inhalers, hospital bills, rent—a lot of things are more expensive here, because of all the other things that are cheap.

This made the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s plan for congestion pricing in Manhattan, which was scheduled to begin later this month—after 17 years of planning, legislating, study, and litigation—something of a miracle. For once, the priorities were in order. New York proposed that the people who contribute to a problem should subsidize the solution. Drivers would pay a $15 toll for entering a “congestion zone” south of 60th Street during peak hours (it’s only $3.75 off-peak). The fees would net the MTA about $1 billion annually, which it would use to finance a $15 billion capital plan. That money would pay for long-needed improvements and upgrades to subways, bus lines, and commuter rail.

If all went according to plan, a significant number of drivers would choose mass transit instead—pushing still more funds into the agency’s coffers, improving air quality, and reducing carbon emissions. It would also ease Manhattan’s notorious gridlock, enhancing commutes for people who really did need to drive. Hence the name.

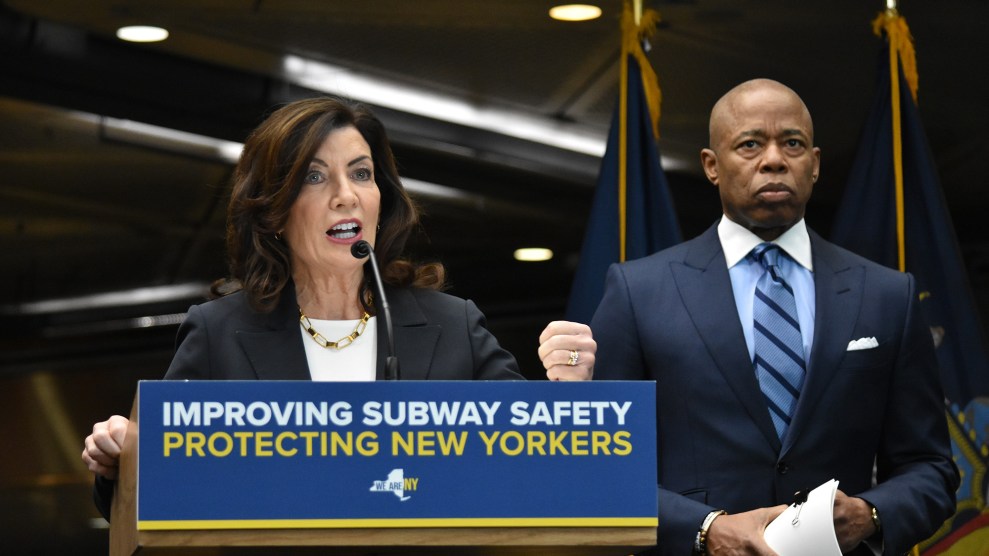

In a speech last month, Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul evoked images of cars “spewing exhaust” and noted that New York commuters spend an average of 102 hours a year stuck in traffic. “It took a long a time because people feared backlash from drivers set in their ways,” Hochul said, acknowledging the stop-and-go pace of implementation. “But, much like with housing, if we’re serious about making cities more livable, we must get over that.”

Hochul, it turned out, was not serious. On Wednesday, she pulled the plug on the plan, 25 days before it was finally set to begin, and one day before the legislative session in Albany was scheduled to end. In lieu of a press conference, Hochul released a pre-recorded video stating that implementation would be delayed “indefinitely,” citing her fear that the program would place an “undue strain” on drivers and hamper the city’s economic recovery. Her words left the door open for the program to start up again later, but not a lot of optimism that it would.

We’re addressing affordability and the cost of living in New York.

— Governor Kathy Hochul (@GovKathyHochul) June 5, 2024

Watch: https://t.co/rdFzgTf72D pic.twitter.com/cDv3lLHdaN

Congestion pricing has drawn a lot of backlash, with the ire increasing as the start date approached. Disgraced former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who signed the plan into law during his third term in office, has emerged as a high-profile critic as he reportedly mulls a run for mayor. The current mayor, Eric Adams, has tried to wash his hands of the idea and proposed all manner of carve-outs. One state assembly candidate recently proposed an exemption for “union members.” I don’t really know why.

Much of the criticism has come from out-of-state lawmakers speaking on behalf of far-flung and affluent commuters. Rep. Josh Gottheimer pushed legislation to stop it. Sen. Bob Menendez introduced a bill to divert federal highway funds from New York state in retaliation. Gov. Phil Murphy argued in court that the law was unconstitutional because it discriminates against New Jersey, a state that is, at the risk of discriminating against New Jersey, mostly one big toll. (The MTA ultimately promised to send New Jersey millions of dollars from the program for mass-transit projects.)

The sort of people who could not generally care less if Exxon opened a refinery in your child’s pre-school started demanding environmental reviews and pointing to adverse impacts in communities that will receive increased truck traffic as a result. That redistribution of pollution is a real side-effect that the state is obligated to spend $130 million to mitigate, but also something that’s hard to talk about with a straight face when you’re arguing that more people should drive.

Hochul’s gambit is inherently self-defeating

The most recent addition to the anti-congestion-pricing coalition was Trump, who gets around by helicopter, private jet, and motorcade, and, like many New York Post readers, currently resides in Florida. “It is a big incentive not to come—there are plenty of other places to go,” he Truthed in May, on the eve of his hush-money trial. “It’s been a failure everywhere it has been tried, and would only work if a place were HOT, HOT, HOT, which New York City is not right now. What office tenant or business would want to be here with this tax. Hopefully, it will soon be withdrawn!”

It was sort of like the Simpsons‘ Monorail in reverse—a shady huckster desperately warning people not to adopt a good idea that’s worked everywhere it’s been tried. But all that political pressure worked. According to Politico, Hochul came around to the Trump–Menendez–Gottheimer consensus after being lobbied by House Minority Leader Rep. Hakeem Jeffries—whose constituents mostly rely on public transit to commute to Manhattan and now stand to suffer delays and deteriorating service for their sins.

Jeffries was reportedly concerned that the toll would hurt Democratic candidates in swing districts that are part of its roadmap to retaking the House. That includes places like the Hudson Valley, where Republican Rep. Mike Lawler is facing former Rep. Mondaire Jones, who said congestion pricing is “long overdue” two years ago when he was running for a different seat that included parts of Lower Manhattan and North Brooklyn. The news had barely leaked on Wednesday before Lawler was out with a statement calling it a “blatant election-year…stunt.”

That seems pretty obvious, but it’s also a deeply strange election-year stunt. For one thing, suburban commuters mostly arrive in Manhattan by commuter rail, which was supposed to get $3 billion from the $15 billion in bonds that would finance the plan. (The $1 billion in annual toll revenue would then pay the interest on the bonds). And Hochul put the brakes on Plan A without really figuring out a Plan B, or even, apparently, talking to anyone about it. She promised that she’d find the money somewhere else, but the state senate’s finance committee chair expressed shock at the news and warned that the governor had “single-handedly created a financial and fiduciary crisis at the MTA.” (Inspiring!)

The closest thing to a counter-offer from Hochul was a proposal to raise payroll taxes on New York City businesses. It’s the kind of political calculus that makes you gasp: Why get drivers in different states to offset the costs when you can raise taxes on your own voters in an election year? How has no one ever thought of this? An MTA spokesperson previously told Gothamist that “more than 20,000 jobs are at risk of delay and disruption” if the plan didn’t go through because of litigation. A long-term capital project involving something that foundational to the regional economy is not something to mess with on a whim.

The congestion pricing plan was not perfect. There was no radical reimagining of city streets in the offing. The state is already dipping into a fund for public transit to subsidize car commuters in the outer boroughs, which runs counter to the whole idea. But it was a big deal, not because it was novel—similar programs have been huge successes in London and Stockholm—but because it was happening at all at a time and place when the various chokepoints of 21st-century politics sometimes make even the smallest reforms seem impossible. If you believe that a government should do things, it’s important to demonstrate that it can.

Hochul, in an election year, is doing the opposite.

At a rally with transit advocates in December, Hochul declared that congestion pricing was an idea for people who are “sick and tired of gridlock,” “people with disabilities [who] deserve to have better accessibility when they travel,” and people who want “cleaner air for our kids and future generations.” “This is where we demonstrate leadership,” she said.

What is it now then? When you pull the plug on a landmark program that the state has spent millions of dollars and years (and years!) putting into a place—a program for which the cameras have already been installed—because you think it might net a few hundred votes to Mondaire Jones, you are undercutting the entire point of politics. There have been a lot of now-meaningless words, but also an incalculable amount of now-meaningless work.

This plan was proposed in 2007. It was greenlit by the city council in 2008. It was backed by the governor in 2017. It was passed by the legislature in 2019. It was approved by the Department of Transportation in 2023. Hochul’s gambit is inherently self-defeating, because it tells a story that’s more damaging to her brand, and to her party’s, than any toll charge: It is not a political win to announce to the public that your government is broken and it can’t do big things.