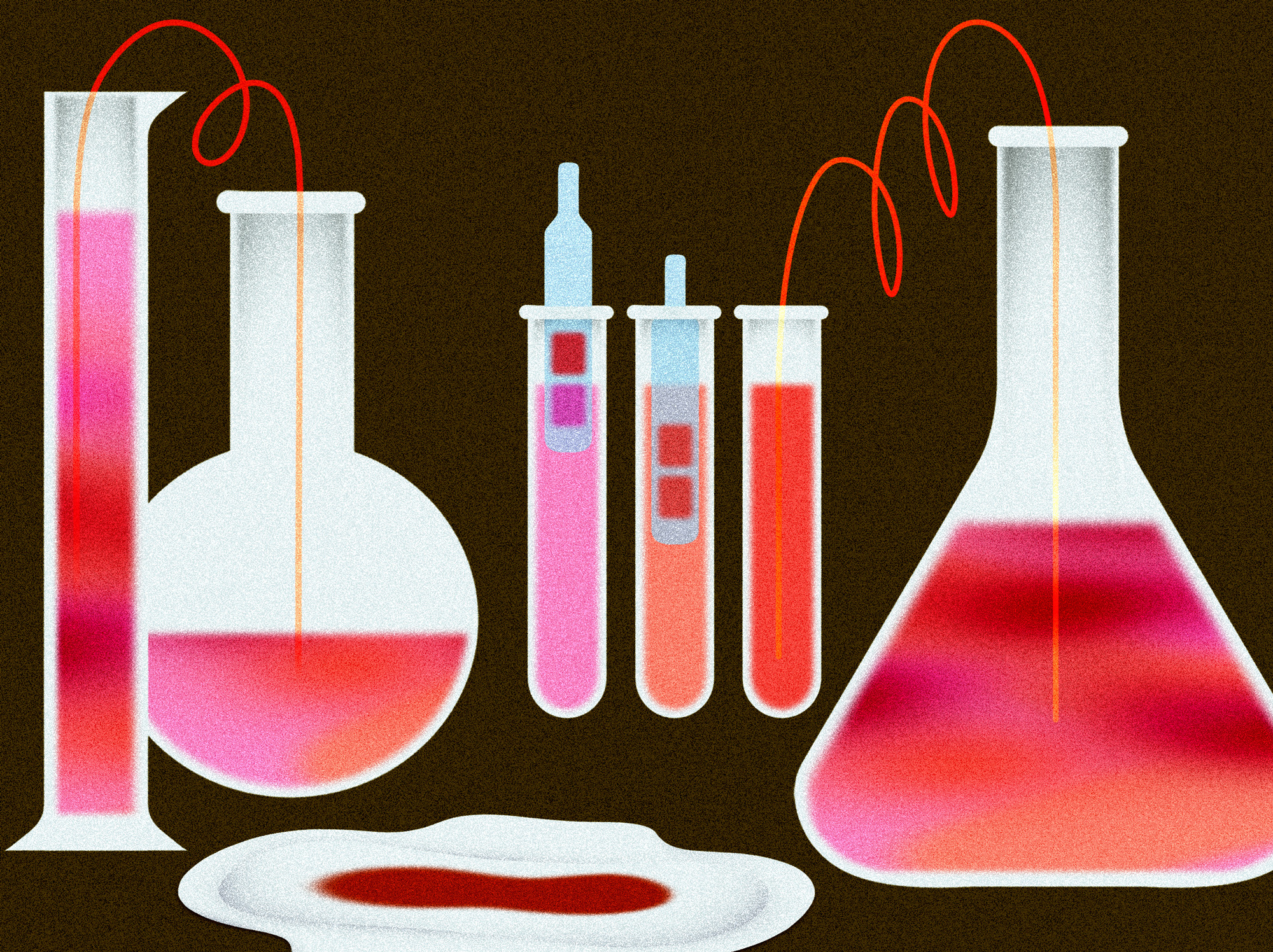

On a Wednesday in early March, a lab scientist named Carlo removed a paper strip containing a dried blood sample from a plastic envelope. He inserted it into a contraption resembling a large hole punch, and I watched as a small wine-colored disc dropped into a test tube. Next, he would add a buffering solution and feed the tube into a chemistry analyzer, a machine resembling a short tanning booth that scanned the sample for a glucose level indicator.

Neither the futuristic machines nor the test itself was uncommon. What was unusual, surprising, maybe even revolutionary, was that the substance he was examining was not blood from a vein or a finger prick, but from menstruation.

I had traveled to the Silicon Valley headquarters of a startup called Qvin, pronounced “kwin,” derived from the Danish word meaning “woman.” Since receiving clearance from the FDA in January, Qvin has begun selling a new menstrual pad that it says will help people tap into the “power in your period.” Rather than undergo a blood draw, a woman (and anyone who menstruates, but for this story, I will sometimes refer to women because they dominate the group that does) can stick the $49 Q-Pad, as it’s called, in her underwear during her monthly flow. She then pulls out a test strip, which will have dried the blood and primed it for transport.

Currently, Qvin’s lab analyzes the sample only for its average blood sugar level, a biomarker (essentially, a signal of a disease or condition) used to diagnose two types of diabetes. The company says it hopes to soon offer other tests, including for HPV—the virus responsible for 95 percent of cervical cancers—and for fertility hormones.

Qvin is part of a small but growing wave of companies and research initiatives doing something that science and medicine have neglected for thousands of years: treating menstrual blood not as a waste product, but as an important trove of information about the bodies it comes from. I’d become especially interested in the new science of periods after a baffling diagnosis left me grasping for more details about my reproductive organs and wishing medicine had more answers to give.

“No, no, no, that can’t happen,” Blumenthal recalls him saying. “I’m not letting you put that skanky stuff in my machine.”

“Period blood is the most overlooked opportunity in medical research,” Qvin co-founder Dr. Sara Naseri likes to say. Collecting it is noninvasive. And data hidden in its cells might help scientists crack the code to some of the most cryptic reproductive ailments.

One of those is endometriosis, wherein tissue resembling the type that lines the uterus invades areas outside the womb. Given its complexity, frequent painfulness, mysterious etiology, and lack of a cure, the disease is a research white whale. Dr. Christine Metz, a professor at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell Health who co-directs a prominent endometriosis study, says she was shocked a decade ago when she realized menstrual effluent—which contains cells shed from the uterine lining—had rarely been considered as a window into a woman’s reproductive organs. It’s like “a biopsy of the endometrium,” she says.

Other researchers are examining period blood’s potential to treat diseases. The uterus is an incredible organ for many reasons, chief among them is that it repairs itself—without scarring—after shedding its tissue every month or so during a person’s reproductive years. It does this with the help of stem cells, some of which are present in menstrual effluent. There have recently been clinical trials testing the use of these stem cells for conditions such as infertility and severe Covid, and studies showed they helped with wound healing and stimulating insulin production in diabetic lab mice.

Even so, scientists studying menstrual blood say they have been met with a reluctance rooted in cultural taboos about menstruation. The queasiness continues to hamper research, obscuring discoveries that—considering every single day, hundreds of millions of people worldwide are menstruating—may be hiding in plain sight.

In 2014, when Naseri began to explore the possibility of using periods to diagnose disease, she approached the lab director at a high-ranking university hospital and asked if she could run some experiments. He refused. Naseri’s research partner, Stanford OB-GYN professor emeritus Dr. Paul Blumenthal, offered to spin the blood down, separating the serum from the red blood cells that give the substance its intense color. But the lab director still wouldn’t budge. “No, no, no, that can’t happen,” Blumenthal recalls him saying. “I’m not letting you put that skanky stuff in my machine.”

Blumenthal believes the lab director’s disgust reflects a deep-seated perception that menstruation is “a topic that is not discussed at the dinner table and that menstrual blood itself is kind of dirty.” But, as he sees it, its utility for science might offer an opportunity to rebrand: “If your menstrual blood actually has real value, then it might not be so stigmatizing.”

The cultural opprobrium regarding menstruation is ancient. Rome’s Pliny the Elder claimed in Natural History that a menstruating woman would cause wine to go sour, gardens to wither, and bees to die. Many major religious texts sought to seclude women during their monthly cycles, from the Hindu Vedas to the Old Testament, which declared that anyone who touches her “will be unclean until evening.” In early modern England, according to historian Sara Read, the popular Geneva Bible instructed people to “cast [false idols] away as a menstruous cloth,” thereby aligning “the rag,” as it came to be known, with corruption.

One of the most stubborn menstrual myths has roots in the ancient Greek idea of the “humors,” four fluid elements—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile—meant to exist in harmony in the body. Because women were supposedly more sedentary than men, they needed to menstruate to flush out the noxious blood and waste that had built up. The medical community held on to similar notions well into the 20th century. In the 1920s, pediatrician Dr. Béla Schick helped popularize the concept of “menotoxin”—a substance menstruating women supposedly secreted that could wilt flowers, give children asthma, and cause all sorts of female maladies. Menotoxin appeared in articles and letters published in the prominent scientific journal The Lancet until the 1970s.

Some scientists have hung on to such superstitions, as Italian researcher Federica Marinaro discovered in 2021. She and a group of her peers at a Spanish research center had just completed a study on the anti-inflammatory abilities of menstrual stem cells, which are similar to those culled from umbilical cord blood or bone marrow. The team submitted its paper to different journals, and as is common, a few journals rejected it for one scientific quibble or another. But one response from an anonymous peer reviewer at a prominent international science journal stopped Marinaro in her tracks: The reviewer rejected the article based on the “severe undesirable and toxic effects of menstrual blood and all its constituents on the human body,” they wrote. “Even in all religions, it is well known that menstrual blood and its stem cells are extremely toxic and of very low quality,” the reviewer continued, going on to suggest that women in some cultures use drops of menstrual blood to kill their husbands.

The response “was shocking,” Marinaro says. But even if it was preposterous, it made her and her team doubt themselves for a time. “We started to think, maybe, are we doing something wrong? Maybe we didn’t check enough,” she recalls, “before saying, ‘You’re totally crazy!’”

A PubMed search yields only about 400 papers referencing “menstrual blood” in the last several decades, compared to around 10,000 related to erectile dysfunction.

Centuries of shame have ensured that periods have been understudied and underrepresented in medical literature. It didn’t help that women of reproductive age were excluded from most US clinical trials until 1993, leading to a gender data gap in health research. As Blumenthal and his fellow authors of a recent editorial in the journal BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health note, a PubMed search yields only about 400 papers referencing “menstrual blood” in the last several decades, compared to around 10,000 related to erectile dysfunction. While a few pioneering scientists are inching the conversation forward, and a push by public health advocates in recent years has raised awareness about the need for menstrual education and equity, Western medicine by and large continues to avoid periods as a subject for serious scrutiny.

If you are a person who menstruates, you’ve dealt with period-related drama and stress. You’ve avoided pool parties and dates, winced when the tampon box was empty, spent afternoons curled around a heating pad. You’ve kept tabs on your period to avoid getting pregnant, or to try to get pregnant; many of us spend ungodly quantities of money and mental energy on one or the other at different stages of our lives.

Several years ago, after the close tracking of my period for 15 months failed to help my husband and me conceive, and hundreds of dollars of tests showed no abnormalities, a doctor at a private clinic finally diagnosed me with “unexplained infertility.” It is a relatively common diagnosis, and a maddening one: There is likely something wrong with you, the reasoning goes, but research hasn’t gotten us to the point where we can determine what it is. Microscopic endometriosis was mentioned as one possibility. Egg quality was another. (“Maybe your eggs are too hard?” one doctor suggested.) But for the most part, it felt as if I were being encouraged not to worry my little head about what was going on down there. “We might never know what’s wrong,” the doctor said in so many words, “but the good news is, our interventions are often successful for people like you.” For tens of thousands of dollars and a strong cocktail of self-administered hormone injections, I entered my body into a gauntlet of trial and error while hoping for the best. But I couldn’t stop pining for a clearer view of my troubled cells.

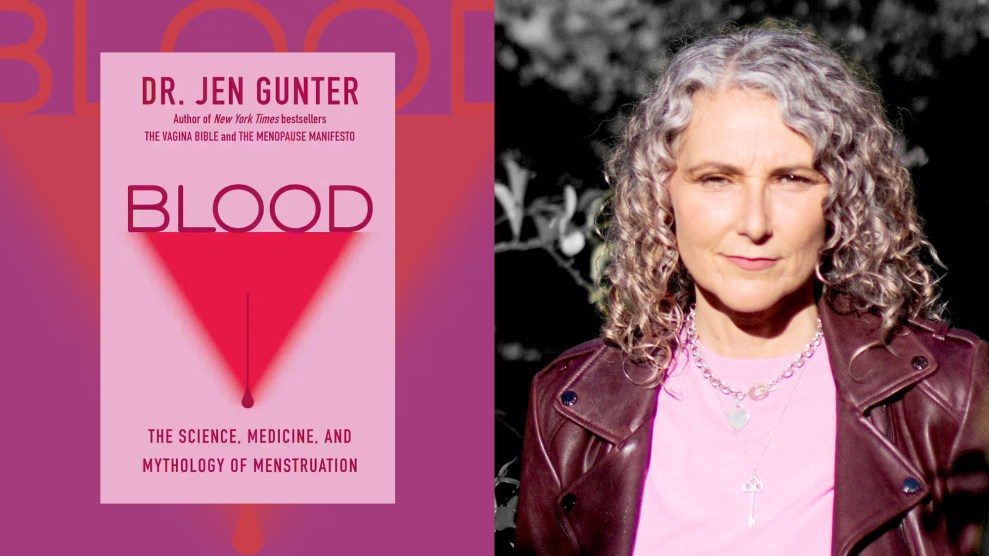

There is still much about the reproductive system that remains uncharted. Science isn’t even entirely settled on why humans leak tissue-laced blood at a regular cadence. Menstruation (from the Latin menstruus, meaning “monthly”) is the regular shedding of the uterine lining, also called the endometrium. Current theory holds that this regular bleeding is an extravagant byproduct of the menstrual cycle and “not the point,” explains OB-GYN Dr. Jen Gunter in her 2024 book, Blood: The Science, Medicine, and Mythology of Menstruation.

Seven to 10 days after ovaries release an egg, the hormone progesterone instructs the uterine lining to thicken in preparation for a possible pregnancy. The lining doesn’t just thicken—some endometrial cells also physically change to store sugars and fats and provide nutrients to a possible embryo, a process called decidualization. Gunter explains it using the analogy of soufflé baking, which requires utmost precision, with steps that must occur in an exact sequence. Once the souffle is baked, it “can’t be turned back into a bowl of egg whites and another of egg yolks.” In the same way, when the endometrium has transformed in preparation for pregnancy, its cells can’t revert to their original states, to be broken down by the body and reabsorbed. Instead, the lining sheds and the cycle starts anew.

In the 98 percent of mammals that don’t menstruate, the uterine lining remains unchanged unless an embryo implants. Humans, though, experience spontaneous decidualization, meaning the same preparatory transformation happens whether an embryo implants or doesn’t—the soufflé gets baked either way.

What makes this resource-intensive process worthwhile? It seems to have two evolutionary advantages. It nudges the endometrium to grow extra thick. This helps a mother fend off the invasive human placenta, an organ made up of her and her fetus’s bodies, with “one side that’s always hungry, and one side that’s trying to protect itself from that hunger,” as researcher Cat Bohannon puts it in her 2023 book, Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution. “Human women menstruate because it’s part of how we manage to survive our bloodsucking demon fetuses,” she writes.

Spontaneous decidualization also is thought to allow the endometrium to perform a kind of internal natural selection, helping to pinpoint the fittest embryos by acting as a biosensor of quality, Gunter explains: If the decidualized lining picks up anomalies in an implanted embryo, “an inflammatory response can be triggered to end the pregnancy.” In short, spontaneous decidualization makes for more healthy pregnancies in humans. The trade-off? Regular menstrual bleeding.

But not everyone is convinced that menses are only a byproduct. As biological anthropologist Kate Clancy writes in her 2023 book, Period: The Real Story of Menstruation, some scientists have begun to make the case that menstrual effluent—which is swimming with special proteins and enzymes, along with stem cells—is an essential ingredient in healing the endometrium and helping it rebuild. In other words, maybe menstrual blood has a purpose when it’s still inside the body.

What is becoming increasingly clear is that period blood contains messages about the landscape of organs through which it has passed. Qvin co-founder Dr. Sara Naseri was studying to be a physician in Denmark, her home country, when she first started considering its clues. I met up with her at a hotel cafe in San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood; she arrived by bicycle and plopped her helmet on the table. The daughter of Iranian immigrants, Naseri grew up in Aarhus, Denmark’s second-largest city. At age 17, after a close neighbor died of skin cancer, she and a friend invented a new chemical compound to protect against UV radiation. “Sara was like a whiz kid,” her Qvin co-founder, Søren Therkelsen, tells me—“hella smart.” The product didn’t pan out, but Naseri remained driven to help people be more proactive about their health.

Once she was in med school, it seemed like most of the training was focused on reactive care—diagnosing problems and figuring out treatments, rather than preventing them or detecting them before they got serious. Naseri recalls thinking: How can we obtain information about our bodies early, outside the doctor’s office? Since of all the bodily fluids clinicians use to monitor health, they most often turn to blood, Naseri wondered how it could be accessed more conveniently. She was in a class when it struck her: “Hold on a minute—women bleed every single month. Why has nobody looked at that?”

Part of the reason few people had, she would soon learn, was that fellow clinicians generally thought the substance was gross. A male colleague researching feces was disgusted to discover that Naseri was interested in scrutinizing period blood. Pause on that for a moment: Even a feces researcher thought menstrual blood was off-limits. “He’s not a bad person, you know,” Naseri says, “but that was just kind of the mentality.”

A male colleague researching feces was disgusted to discover that Naseri was interested in scrutinizing period blood.

She jumped on PubMed to see what had been published about the protein makeup of menstrual blood and found only one paper. “I was shocked when I realized where it was from,” Naseri says: It had been commissioned for use in criminal investigations, to help forensic scientists distinguish the blood from other fluids. Naseri flew to New York to meet with the paper’s author, Donald Siegel, a clinical assistant professor of forensic medicine and pathology at New York University, to ask him how to run a clinical trial on this understudied substance. Unlike Siegel, who focused on how menstrual blood differed from the systemic blood produced by wounds or veins, Naseri wanted to see how the substances correlated—to show that periods might offer the same intel as a trip to a phlebotomist.

By 2014, Naseri and Therkelsen, a tech entrepreneur and fellow Dane, had been matched through a tech mentorship program sponsored by Intel. As the at-home diagnostics industry began to take off (think smartwatches and microbiome testing), the duo formed Qvin.

The next year, Naseri approached Stanford’s Blumenthal, an OB-GYN professor and international public health adviser, about the idea of using periods for diagnostic purposes. (She heard that “he’ll try anything,” Blumenthal joked when I asked him what had led Naseri his way.) He helped her secure a position as a visiting student researcher at Stanford. A few years later, Naseri and Blumenthal published a study showing that many of the same biomarkers in blood drawn from veins turned up in the same levels in menstrual blood. “They were pretty much bang on,” Blumenthal explains. While the study wasn’t huge, its findings supported the idea that monitoring periods could become an alternative form of testing for major diseases.

The prospect offered tempting advantages. Most people dread pap smears, an invasive procedure involving a doctor’s visit, stirrups, a speculum, and the “sweeping” (read, painful prodding) of the cervix to harvest its cells and test them for HPV. Because menstrual blood passes through the cervix on its way out of the body, it contains some of those very cervical cells, no pap smear required—a boon especially to patients for whom past sexual trauma or disabilities make the procedure, if not impossible, a source of extreme discomfort or anxiety. Qvin says it plans to offer an HPV test for use with its Q-Pad soon.

Because menstrual blood has also spent time in the uterus, it could be tested for cytokines, proteins that serve as chemical messengers in the immune system and can provide insight into inflammation and disease in the uterus. Testing these has traditionally involved laparoscopy or other invasive sampling. But the testing could be done on menstrual blood instead, as a small 2023 study by Blumenthal and Naseri and a few other researchers suggested.

Key to understanding the blood’s messages was figuring out a way to collect it. For Naseri and Blumenthal’s first study, they had asked their participants—many of them Stanford students—to collect the fluid with menstrual cups. Some were uncomfortable with the device and as a result, declined to participate in the study. There were additional concerns that the blood would start to degrade after being left too long in the cup, not to mention the extra red tape involved in shipping a liquid biohazard through the mail.

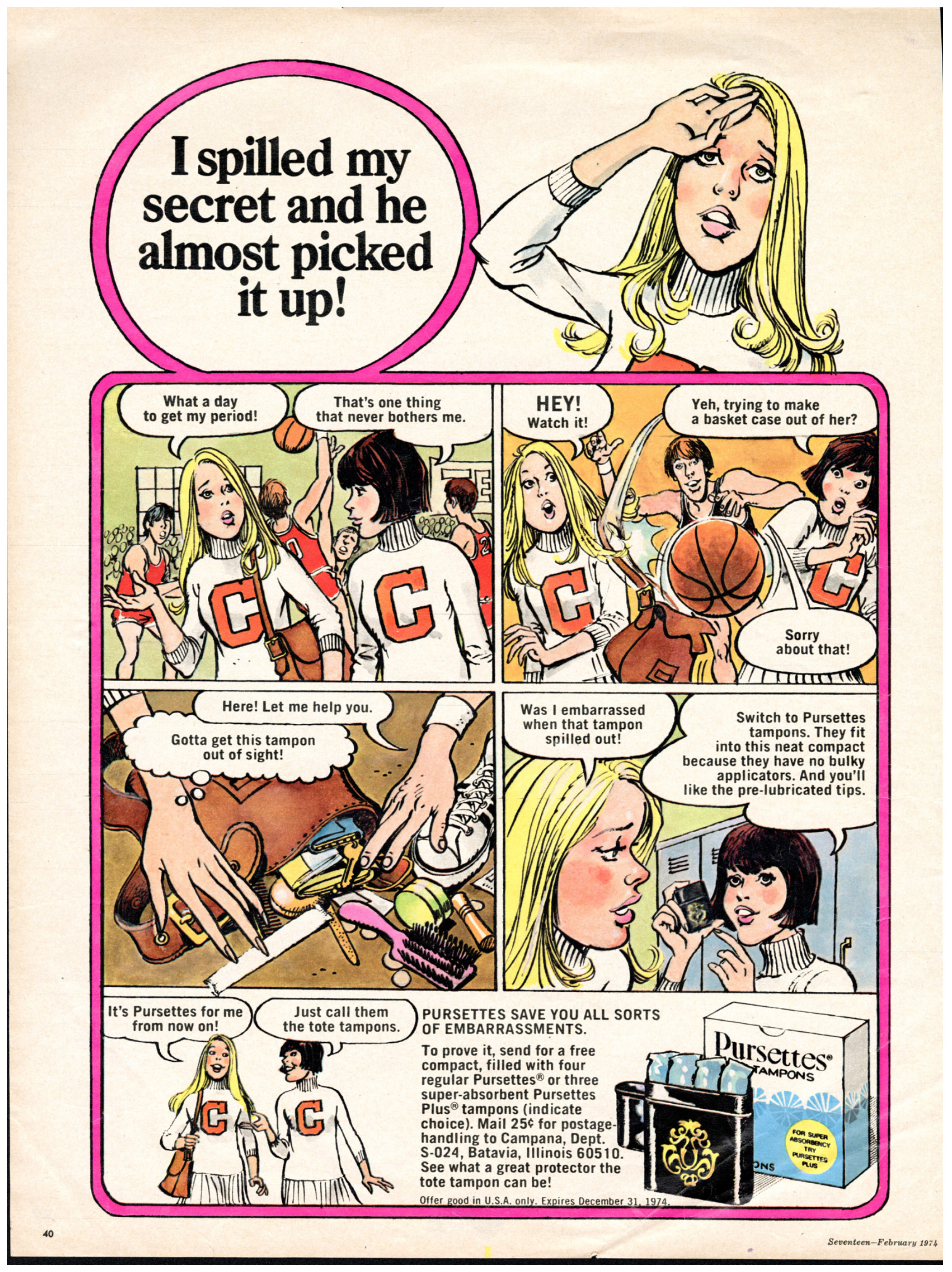

The team then turned to a time-honored menstrual blood collection device, the pad. Companies first began marketing disposable pads to Americans in the late 1800s, but the products really took off in the 1930s and ’40s with the help of big advertising campaigns—many of which emphasized secrecy and the need to hide periods from public view. Naseri and Therkelsen’s earliest idea was a sophisticated menstrual pad embedded with biosensors that could test for diseases right then and there. “In the beginning, the idea of the product was to build the laboratory, tiny, into the pad,” Therkelsen explains to me during my tour of Qvin’s office in Menlo Park, California. Therkelsen, a towering blond in colorful Nikes accompanied by his two Labradoodles, Cassini and Juno, pulls out an early prototype, a calculator-sized board with little silver pins on it.

The idea of building a lab inside a pad is reminiscent of an infamous blood-testing startup. On our tour, Therkelsen whips out a folder labeled “Theranos” and shows me the worn Elizabeth Holmes business card inside. During Qvin’s early days, he met Holmes (later convicted of fraud and sentenced to 11 years in prison) and tried to dig into her technology. In retrospect, Naseri and Therkelsen learned much more from Theranos’ mistakes. They even brought on entrepreneur Tyler Shultz—Theranos board member George Shultz’s grandson and the whistleblower who helped expose Theranos’ fraud—to consult on transparency and other best practices.

After many iterations and years of testing—with the help of a menstruating robot named Betty made with pulleys and a gently rocking bicycle seat—the team perfected a pad design that eschews circuitry for a simpler approach. The pad’s paper, for instance, dries menstrual blood upon contact, aiding with the preservation and transport of the samples. (The same dried blood spot technology is used with the heel pinprick test given to newborn babies.)

The Q-Pad hit shelves in early January. An accompanying press release promised it had the potential to slash health care costs; the pad could take the place of phlebotomists. Patients could soon receive reports on “key health conditions that often go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed,” including fertility, perimenopause, and endometriosis.

The fine print, though, states that the Q-Pad can’t be used to diagnose any diseases; it is meant as a supplement to regular visits to the doctor. It is currently approved in the US only for use with the A1c (average blood glucose) test. Whether it could further patients’ understanding of reproductive maladies remains to be seen.

Members of the Qvin team are not the only researchers looking into menstrual blood’s clinical and market potential. In 2013, a group of scientists at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell Health launched what is likely the longest-running study of endometriosis, called the Research OutSmarts Endometriosis (ROSE) study.

The disease is often chronically debilitating for the 5 to 10 percent of people of childbearing age who have it. Many of them are unable to get pregnant. Researchers have estimated that endometriosis costs the US medical system and economy as much as $119 billion a year due to treatments, lost productivity, and other burdens. It’s also notoriously hard to pin down—it takes an average of four to 11 years after initial symptoms to diagnose it (and longer for people of color), and an official diagnosis requires surgery, or often several.

Endometriosis costs the US medical system and economy as much as $119 billion a year.

The ROSE study team wanted to figure out a less-invasive way to detect the disease. When they compared the menstrual blood of women already diagnosed with endometriosis with a control group, they found that endometrial cells in their effluent contained fewer markers that were sensitive to the hormone progesterone; fewer uterine natural killer cells, which are also thought to play an important role in fertility; and more B cells, which are associated with chronic inflammation. “We think this gives us more of a concept of what this disease is,” study co-founder Dr. Christine Metz explains. She thinks the research will eventually lead to an FDA-approved test that could allow doctors to diagnose endometriosis without surgery.

Metz almost teamed up with Qvin, but the partnership didn’t work out. Metz thinks the blood drying paper employed by the Q-Pad doesn’t sufficiently preserve the endometrial tissue—which, in her eyes, contains “the answer to really understanding the disease.” (A Qvin spokesperson stated in an email that endometriosis “can be analyzed in a multitude of ways” and that the company maintains a library of collection devices used for different types of tests.) Metz has since partnered with another company on a different menstrual collection device, but she wouldn’t give me any more details. “We don’t want to announce something prematurely that’s going to fail,” she says.

Metz worries that a less-than-perfect product launch by any company might inflict further damage on a field of research that already has struggled to attract support. Much of the federal funding for reproductive health research comes out of the National Institutes of Health’s arm focused on child health, which has one of the smallest pots of money in the agency, “so the funding line is just abysmal,” says Clancy, the biological anthropologist and Period author. A 2021 analysis of NIH data showed that “the funding of research for women is not aligned with burdens of disease,” Sarah Temkin, associate director for clinical research at the agency’s Office of Research on Women’s Health, told a reporter at the journal Nature last year. For instance, between 2007 and 2014, gynecological cancer research received far less investment in proportion to its lethality than other cancers like prostate cancer (though worth noting that breast cancer receives quite a bit as well). “We can only have home runs because funding in women’s health is really low,” Metz cautions. “We can’t afford disappointments.”

Clancy, who runs a lab studying the impact of environmental stressors on women and gender minorities, doubts there has been enough menstrual science to justify any diagnostic products hitting the market. There’s still a lot we don’t understand about the uterus and menstruation, she says. “I think we really need to take a step back and say, ‘Have we actually done the basic research to fully characterize this, to understand how it varies between people, how it varies with the environment, varies through the life course?’ Before we start saying, ‘We could measure this and get money for it.’”

My doctor’s prediction was right. IVF was eventually successful, and signing up for it is a decision I will never regret. But while I now have a son, all the trial and error yielded no new revelations about my uterus. It’s hard not to wonder: If medicine had long ago shown a bat squeak of interest in menstrual blood, how much more knowledge would we now hold about our insides and what makes them tick?

If medicine had long ago shown a bat squeak of interest in menstrual blood, how much more knowledge would we now hold about our insides and what makes them tick?

In the future, doctors may take a different approach. Rather than waiting for problems to arise or fester, they’ll use our periods to monitor our hormonal and cellular ecosystems from a young age, picking up everything from environmental contaminants to infections, Metz predicts. “We think that the legs that menstrual effluent has are enormous.”

New discoveries about the complexities of female biology are already transforming our understanding of disease, medicine, and even what it means to be human. “There’s a quiet revolution in the science of womanhood brewing,” writes Eve’s Bohannon. “It is early days,” Naseri says. “We are just scratching the surface of what’s possible.”