Mother Jones; Engin Akyurt; Tim Mossholder/Unsplash (2)

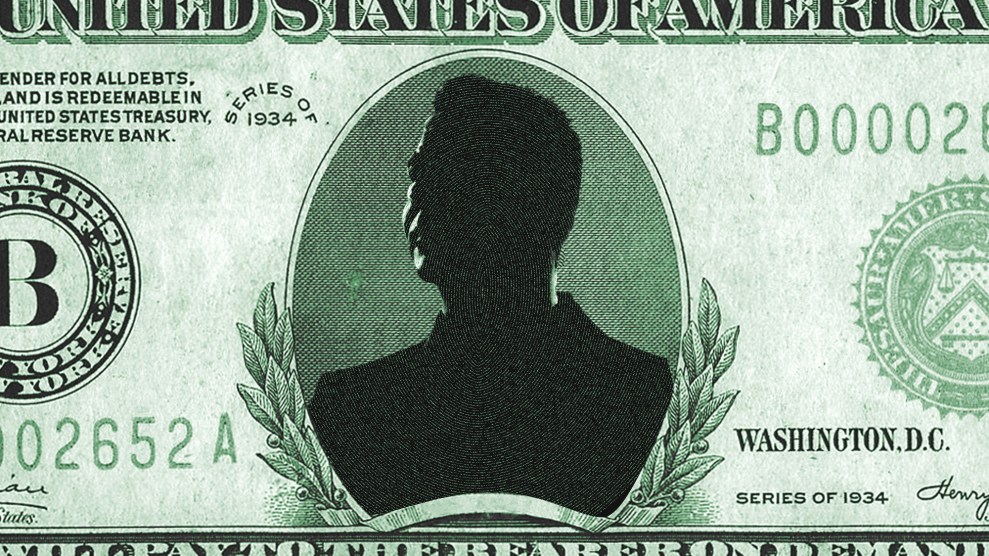

In December, I published an interview with the tax policy expert and attorney Steve Rosenthal titled “The Supreme Court Case That Could Upend a Century of Tax Law.” Dropped last week, the high court’s ruling in that case, Moore v. United States, was narrow and thus relatively inconsequential on the real issue—whether Congress has the power to tax unrealized wealth. But that dangling determination will come back to haunt us.

The tl;dr is that the Moore case was bankrolled by a conservative group whose agenda wasn’t to save petitioners Charles and Kathleen Moore $15,000 in taxes. Rather, it was to solicit a ruling that would render a whole bunch of proposed wealth taxes unconstitutional.

Nearly all of the wealth of super-rich Americans is tied up in “unrealized” gains, paper profits on unsold assets like stock or fine art or vintage Ferraris that have appreciated in value. Those gains are currently taxed as income only when the assets are sold (or “realized”). Even then, the maximum tax is 23.8 percent, as opposed to the 37 percent rate that high earners pay on work income in excess of $609,351 a year.

That difference in rates, favoring capital over labor, is a huge and poorly justified perk for investors—who, it is worth pointing out, are not middle-class Americans. At last count, nearly 93 percent of all stock owned by US households was owned by the wealthiest 10 percent, and a whopping 54 percent was owned by the richest 1 percent of households. ProPublica famously revealed how billionaires with vast stock holdings have reduced their income taxes to practically zero; instead of selling stock for income, they borrow money to fund their lavish lifestyles, using the unsold stock as collateral. An interest rate of 3 to 5 percent is a pittance when you’re avoiding a 23.8 percent capital gains tax.

In Pollock, Justice Harlan dissented, noting it was wrong for the court “to create a special class of privileged people who, alone among Americans, would be constitutionally immune from seeing their fortunes taxed.”

That’s a good enough justification for taxing unrealized wealth, but so far, every congressional effort to do so has failed to get the votes. As Rosenthal points out in a recent Tax Policy Center article, “Congress generally waits to tax income until it’s received—because Congress views that as an “administrative convenience” (it’s easier to count that way), not a constitutional requirement.”

But the people behind Moore wanted, well, more.

They didn’t get it, at least for now. As Rosenthal writes, Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s majority opinion “upheld Congress’s authority to tax undistributed profits…But Kavanaugh refrained from holding that the practice of delaying taxation until realization is founded on administrative convenience rather than a Constitutional demand, notwithstanding prior Court pronouncements.”

The majority, in other words, sidestepped the issue. Rosenthal goes on…

But four Justices (Amy Coney Barrett, Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch) expressly declared that realization is a constitutional requirement. President Biden and Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden (D-OR) have proposed taxes on the unrealized gains of the nation’s wealthiest households. Based on their opinions, these four Justices would find taxing the unrealized gains of billionaires unconstitutional. So, if either Roberts or Kavanaugh (the most likely candidates) joined them in a case challenging a billionaires’ tax, the tax would fail.

Given the value of this prize to the upper crust, it’s inevitable that wealth industry lawyers will mount fresh efforts to get the constitutional question back in front of the court—and more broadly seek rulings that chip away at Congress’ power to levy taxes as it sees fit.

It’s worth noting that the 16th Amendment, which codified that power, was enacted in response to a regrettable 1895 Supreme Court ruling known as Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co. Here’s the snapshot:

The Constitution requires that “direct” taxes must be apportioned among the states based on their population. In Pollock, a 5-4 majority busted precedent by redefining income taxes—which then applied only to incomes north of $4,000, a lot back then—as direct taxes. This, as legal scholars Bruce Ackerman, Joseph Fishkin, and William E. Forbath explained in an amicus brief in the Moore case, “precluded Congress from enacting them at all, since they were not, and could not practically be, apportioned by population.”

The primary dissenter, Justice John Marshall Harlan, they wrote, “argued that it was wrong for the Court to create a special class of privileged people who, alone among Americans, would be constitutionally immune from seeing their fortunes taxed.” The majority, the scholars elaborated, was “imposing on the Constitution its own specific and highly controversial view of political economy,” and at the core of this view “was a profound opposition to redistributionist politics.”

Sound familiar?

The public was shocked and outraged by the Pollock ruling, according to Ackerman, Fishkin, and Forbath. Fifteen years later, in a unanimous 1900 ruling that upheld a progressive inheritance tax, the Supreme Court repudiated its earlier reasoning. Meanwhile, the widespread popular opposition “led a bipartisan supermajority in Congress to frame the Sixteenth Amendment in the specific terms necessary to reverse Pollock.”

The text of the new amendment was straightforward: “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.”

Incomes, from whatever source derived. That seems to cover the gamut. “Far from imposing a realization requirement,” Ackerman, Fishkin, and Forbath wrote in a footnote, “the Sixteenth Amendment was framed and ratified to halt once and for all judicial misuse of the direct tax clauses.”

But if you imagine that centuries of precedent, proven congressional intent, popular outcry, or some silly amendment will thwart America’s dynasties in their relentless quest to hoard more resources, you would be mistaken. Especially now, when they’ve got a court that’s prone to agree with them.