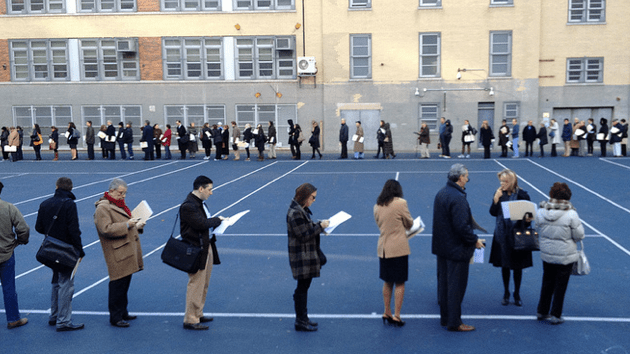

Voters waiting to vote at Wagner Middle School in New York City, Nov 6, 2012.Jeff DaPuzzo/Flickr

When the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 to overturn a key section of the Voting Rights Act last June, Justice Ruth Ginsburg warned that getting rid of the measure was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” The 1965 law required that lawmakers in states with a history of discriminating against minority voters get federal permission before changing voting rules. Now that the Supreme Court has invalidated this requirement, GOP lawmakers across the United States are running buck wild with new voting restrictions.

Before the Shelby County v. Holder decision came down on June 25, Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act required federal review of new voting rules in 15 states, most of them in the South. (In a few of these states, only specific counties or townships were covered.) Chief Justice John Roberts voted to gut the Voting Rights Act on the basis that “our country has changed,”and that blanket federal protection wasn’t needed to stop discrimination. But the country hasn’t changed as much as he may think.

We looked at how many of these 15 states passed or implemented voting restrictions after Section 5 was invalidated, compared to the states that were not covered by the law. (We defined “voting restriction” as passing or implementing a voter ID law, cutting voting hours, purging voter rolls, or ending same-day registration. Advocates criticize these kinds of laws for discriminating against low-income voters, young people, and minorities, who tend to vote for Democrats.) We found that 8 of the 15 states, or 53 percent, passed or implemented voting restrictions since June 25, compared to 3 of 35 states that were not covered under Section 5—or less than 9 percent. Additionally, a number of states not covered by the Voting Rights Act actually expanded voting rights in the same time period.

States that were previously covered in some part by Section 5 moved quickly after it was invalidated. Within two hours of the Shelby decision, Republican Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott announced that the state’s voter identification law—which had previously been blocked by a federal court—would be immediately implemented. Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange, another Republican, also immediately instated his state’s voter ID law. About one month after the Shelby decision, Republicans in North Carolina pushed through a package of extreme voting restrictions, including ending same-day registration, shortening early voting by a week, requiring photo ID, and ending a program that encourages high schoolers to sign up to vote when they turn 18. In October, Virginia purged more than 38,000 names from the voter rolls. Mississippi’s Republican secretary of state, Delbert Hosemann, told the Associated Press in November that the state was going to start implementing its voter ID law by the June 2014 elections. (This proposal was undergoing Justice Department review when the Shelby decision came down.) In January, Republican Gov. Rick Scott attempted again (unsuccessfully) to purge noncitizens from Florida’s voting rolls, a move he had tried previously in 2012, before being blocked by Section 5. And thanks to the Supreme Court ruling, South Carolina was able to implement a stricter photo identification requirement.

But as Wendy Weiser, director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, notes, “Perhaps the biggest impact of Section 5 has always been at the local level.” And there’s been a lot of movement there, as well: After Shelby, Jacksonville, Florida, allegedly moved a voting center that had one of the highest African American voter turnouts in the state to a new site that’s not near public transportation. In Texas, Galveston County eliminated virtually all of the black- and Latino-held constable and justice positions in the county, a move that was previously blocked under Section 5.

Data shows that the law really did work at preventing voting restrictions: Between 1982 and 2006, the Justice Department blocked more than 700 voting changes on the basis that the changes were discriminatory. But experts say it’s hard to say definitively whether all of these new laws would have been blocked if Section 5 had still been in place. The new birth certificate requirements in Arizona and Kansas, for example, would likely have gone forward regardless of the Shelby decision. But Katherine Culliton-González, a senior attorney and director of voter protection for Advancement Project, notes, “There is a heavier concentration of voting restrictions in those states that were previously covered.”

Three outliers are Kansas, Ohio, and Wisconsin, all of which passed or implemented voting restrictions this year, and were never covered under Section 5. But Dale Ho, director of the ACLU’s voting rights project, argues that they could have still been influenced by the Supreme Court decision. “When you see half a dozen or more states immediately passing laws to restrict voting after Shelby, that spreads to other parts of the country,” he says. “It’s not like Vegas. What happens in one state doesn’t stay there.”

Members of Congress have attempted to introduce legislation that would resurrect the key protections shot down by the Supreme Court, but have not yet been successful. And none of this is great news for Democrats, who could lose the Senate in 2014. On Monday, Vice President Joe Biden denounced the GOP effort and urged Democrats to stand up for voting rights. He said, “If someone had said to me 10 years ago I had to make a pitch for protecting voting rights today, I would have said, ‘You got to be kidding.'”