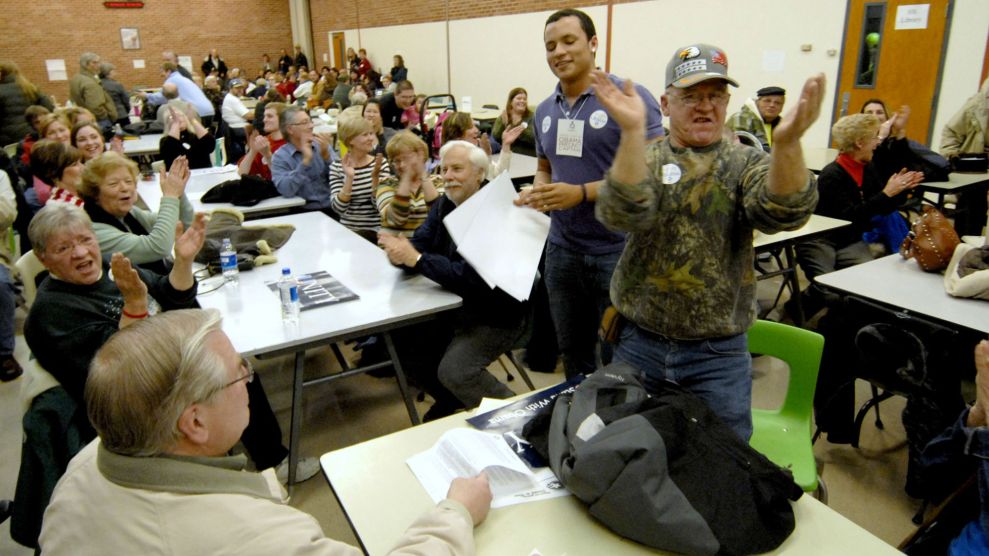

Voters sign in at a Republican precinct caucus in Bloomington, Minnesota, March 1, 2016.Jim Mone/AP

Minnesotans, at least compared to other Americans, love voting. The North Star State regularly leads the country in voter turnout; in fact, the state even clinched an all-time record, when 78 percent of its registered citizens came out to vote in the 2004 election.

But in 2016, it became clear the volunteer party-run caucuses the state had been using for decades weren’t designed for record turnout. As enthusiastic Minnesotans flocked to their precinct caucuses at the appointed time to cast their vote for their party’s presidential nominee, they found the system overwhelmed by sheer numbers. “So many people participated that the system collapsed and it didn’t work,” says state Rep. Pat Garofalo (R-Farmington). “It was a complete shit-show.”

In the Minneapolis elementary school gym where I showed up to caucus that year, so many people came that we ran out of chairs. Some people had to cast votes on Post-It notes because conveners ran out of official supplies. Others never made it into their caucus location at all after searching for parking, navigating the crowds, and waiting in long lines. Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon, a Democrat, says he heard a lot of complaints from voters “about inaccessibility, about chaos, about fairness.”

So this year, Minnesota ditched the caucus in favor of a presidential primary. Instead of crowding everyone at the polls at once, the primary will allow people to vote throughout the day. The primary will also provide early and absentee voting options, opening up the contest to people who can’t attend at a set time on a Tuesday evening.

Only four states are holding presidential caucuses this year (Iowa, Nevada, North Dakota, and Wyoming), down from 15 four years ago. And after Iowa’s caucus practically disintegrated after technological failures and math errors delayed the reporting of vote totals and cast doubt on the integrity of the process, some experts are speculating that the caucus could go extinct. Minnesota’s bipartisan decision to move to a presidential primary could provide some lessons for the rest of the country.

Minnesota is currently home to the only split legislature in the country—Democrats hold the most seats in the state House, while Republicans have a slim majority in the Senate. Yet in 2016, Democrats and Republicans there teamed up to usher in a formal presidential primary for the first time in 60 years.

Crowded caucus room in South St. Paul. #MNCaucus pic.twitter.com/8aIDqqKBKC

— Mark J. Westpfahl (@MarkJWestpfahl) March 2, 2016

Huge turnout, a wide-open presidential contest, and mayhem at both Republican and Democratic caucuses meant both sides of the aisle were motivated to make a change. Because the legislature was in session as the caucuses were happening, they were able to craft a bill right away, “striking while the iron was hot,” says then-Rep. Tim Sanders (R-Blaine), the chief House author and chair of the elections policy committee.

The final bill didn’t get rid of the caucus. It just took presidential primary voting out of the caucus system. (Minnesota held caucuses a week before Super Tuesday this year, where the party faithful voted on rule changes, platform positions, and delegates to conventions. But voting for a presidential candidate now happens separately.)

Despite bipartisan agreement about the need for a new primary system, ironing out the details was tricky. Because switching to a primary would impact how parties nominate their presidential candidates, both the state and national Democratic and Republican parties needed to be involved. One of their requirements, according to Simon, was for the state to start tracking the names of people who vote in each party’s primary. Under the 2016 bill, voters’ party preference would have been public data; a 2019 law intended to protect voter privacy makes it available only to major political parties (the Republicans, the Democratic-Farmer-Labor party, and by a quirk of Minnesota politics, two different minor parties in favor of marijuana legalization).

But that voter data compromise still makes everyone I spoke with uncomfortable. State Sen. Ann Rest (D-New Hope), who authored the Senate version of the primary bill, is sponsoring legislation that would limit the parties’ use of data. Under her bill, the national parties could only use Minnesota primary voter data to comply with the rules for the national nomination process. Rest’s bill would also require the Secretary of State to purge the list after sending this data to the parties. The bill passed out of the state House on February 26. But its future in the Republican-controlled Senate is murky; some lawmakers, like Garofalo, favor a different voter privacy bill. Rest worries that requiring Minnesota voters to declare a party preference will result in lower voter turnout.

How might Minnesota’s switch to a primary affect its election results? “All we can say for sure about the move toward primaries over caucuses is that turnout will likely be higher in 2020 than in 2016 for the states that switch—and that could produce some interesting results,” Geoffrey Skelley wrote on FiveThirtyEight last year. Voters could turn out at a rate of 17-18 percent more, political scientist Caitlin Jewitt told Skelley.

FiveThirtyEight reported that some experts think caucuses tend to favor candidates with grassroots campaigns and deeply committed supporters like Sen. Bernie Sanders, who won almost all of the caucus states in 2016. Other experts are not convinced a rule change will hurt candidates like Sen. Sanders. The most recent polls showed Sen. Sanders coming a close second in Minnesota to the state’s own senator, Amy Klobuchar—but Klobuchar’s decision to leave the race Monday makes Sen. Sanders the new Minnesota front-runner, according to FiveThirtyEight.

Simon, who as Secretary of State now oversees Minnesota’s presidential primary, says other states considering switching to a primary should get the parties involved early and think through voter data privacy in advance. “You have to think about money, too,” he says. While the caucus is run by party volunteers, a primary election is funded by taxpayers. The Minnesota legislature decided to reimburse cities and counties for the cost of the election. But at just under $12 million, the cost of the additional election is going to be more expensive than the legislature anticipated.

Still, the lawmakers I spoke with say it’s worth it. “These two parties are choosing their candidate for the most powerful person in the world,” Rest says. “And the question is, is it worth it to make Minnesotans, Democrats and Republicans, relevant in that decision? And I think that what’s happened is that it was a resounding yes.” More than 66,000 Minnesotans have already voted as of Friday, according to data from the Secretary of State’s office.

And though bipartisan cooperation on any kind of election reform may sound like a wildly unrealistic pipe dream from simpler times, Tim Sanders says that’s what made Minnesota’s primary happen. “If you’re going to move really anything in election policy, bring opponents and proponents together and start with where you agree,” Sanders says. “Because it is possible.”