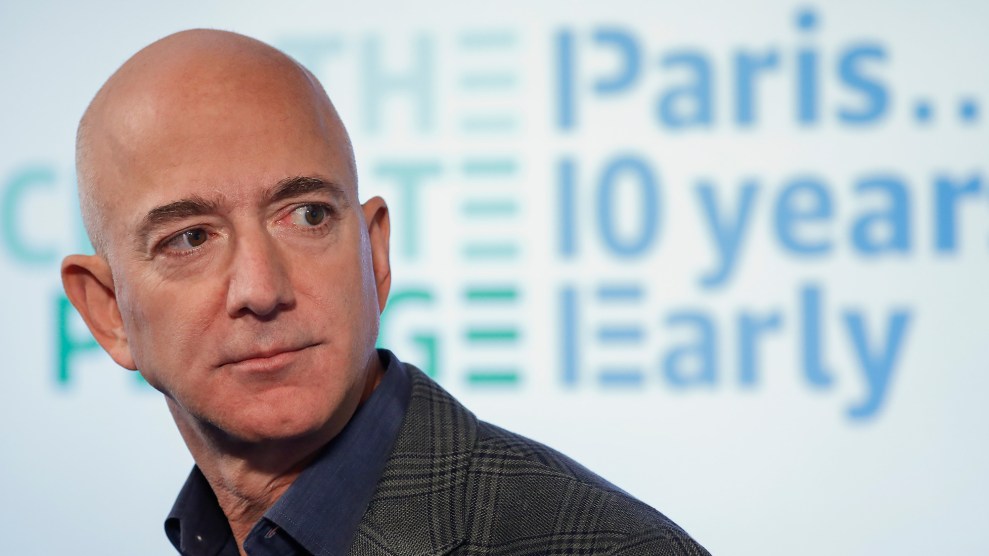

Ted S. Warren/AP

This story originally ran in Wired and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

On Monday, Amazon CEO and world’s richest human Jeff Bezos announced he was pledging nearly 8 percent of his net worth to fight climate change. This money, known as the Bezos Earth Fund, will be used to support “any effort that offers a real possibility to help preserve and protect the natural world,” Bezos wrote in an Instagram post. There are plenty of problems with a billionaire single-handedly dictating how the world community will fight climate change. But it’s also true that there are a host of promising climate technologies that lack the resources to scale fast enough to be effective in meeting the UN’s climate goals. Bezos didn’t specify how he would allocate the Earth Fund’s resources, but if you’re reading this, Jeff, we’ve got some ideas.

Space-Based Solar Power

Right now there are 173,000 trillion watts of solar energy bathing the Earth. If we were to capture just 1 percent of that, it would be enough to meet the world’s energy needs. But soaking up the rays is harder than it sounds. Cloud coverage limits the effectiveness of solar panels, top-of-the-line photovoltaic cells aren’t very efficient at converting sunlight into electricity, and solar power isn’t an option for half the planet at any given moment.

Yet if you were to construct a giant solar farm in space and beam that energy to Earth, the power of the sun would be available around the clock. Isaac Asimov first floated the idea for space-based solar power in the 1940s. A handful of companies like Solaren and Solar Space Technologies have tried to build businesses around space-based solar energy, but lacked the capital needed to bring their technology to fruition.

Last year, the Air Force Research Lab announced a $100 million program to develop the hardware for a satellite that will beam solar power to Earth. If Bezos spent just 1 percent of the Earth Fund to develop space-based solar power, it would effectively double the available funding in the US. If he wanted to sweeten the deal, he could offer solar power satellites a lift to orbit on one of his rockets. Although Blue Origin, Bezos’ space company, hasn’t yet sent a rocket to orbit, they plan to do so by next year.

Enhanced Geothermal Energy

Geothermal power uses superhot water pulled from deep within the Earth to drive turbine generators on the surface. It’s a promising source of inexhaustible clean electricity that could meet the world’s needs several times over. But at present, it accounts for well under 1 percent of the world’s power supply. The problem is that geothermal power is limited to areas that have natural springs with water hot enough to spin the turbines with their steam.

Enhanced geothermal systems are technologies that promise to make the Earth’s energy available almost anywhere. Instead of relying on natural springs, these systems borrow techniques from the fracking industry by drilling deep into hot dry rock and pumping water into the newly created chamber. The water is heated to several hundred degrees and brought back to the surface, where it is used to power a turbine generator. The hot rock needed for these systems is available all over the world. What’s missing is the drilling technology and engineering knowledge needed to access it—drill in the wrong place and you risk triggering a massive earthquake.

Although a number of companies are developing enhanced geothermal systems, they are struggling to raise money to actually build them. Drilling the wells is a very capital-intensive process, and since it’s a new technology it carries a lot of risk for investors. In January, the Department of Energy announced it would spend $25 million on enhanced geothermal systems research, which is hardly enough to get the industry off the ground. Just the interest on the Earth Fund’s bank account would be a major boon to this nascent industry.

Small Modular Nuclear Reactors

Since 2011, Bezos has been investing in General Fusion, a Canadian company attempting to build the world’s first nuclear fusion power plant. It’s a longshot gamble to create an unlimited source of clean energy by essentially building an artificial sun. Fusion works by slamming atoms into each other so that their nuclei fuse and release a tremendous amount of energy. A fusion plant would be able to produce several times more energy than a traditional nuclear power plant, without generating long-lasting toxic waste in the process.

Today, fusion power plants are nowhere close to commercialization. It’s unlikely that we’ll see fusion power hit the grid anytime in the next 20 years due to the challenges involved with sustaining the reaction that makes fusion possible. But in the meantime, Bezos could invest in advanced nuclear fission energy like small modular reactors. Unlike the hulking nuclear power plants of yore, small modular reactors are tiny and can be daisy chained to meet energy needs that vary by region, time of day, or season. The design of small modular reactors reduces the risk of a meltdown, which means they can be placed closer to the cities and towns that need them. They can also be made on an assembly line, which drastically reduces their cost.

But small reactors are hardly the only advanced nuclear technology in development. Thorium molten-salt reactors, for instance, use hardly any uranium. This reduces both nuclear waste and the risk of the proliferation of nuclear weapons by limiting the amount of enriched uranium in circulation. Next-generation fast breeder reactors can use nuclear waste as fuel and have sophisticated cooling mechanisms that limit the risks of a meltdown. While other advanced nuclear technologies are promising, many still have a lot of technological and regulatory barriers to clear before they’re ready to hit the grid. That limits their ability to fight climate change in the near term.

Although nuclear is a dirty word in some environmental circles, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has acknowledged that it will play a vital role in keeping global warming in check. Still, developing nuclear technologies is incredibly expensive and it takes years just to navigate the regulatory hurdles involved in bringing a system online. To expedite this process, the Earth Fund could diversify Bezos’ nuclear portfolio by throwing some money at the fledgling advanced nuclear industry.

Sustainable Hydrogen Production

The eternal promise of a hydrogen economy is using the most abundant element in the universe to heat our homes, store our power, and fuel our cars. Advocates argue that it will save the world by ending our dependence on fossil fuels like natural gas and oil. There’s just one problem: We can’t sustainably produce hydrogen at scale yet. To be sure, we know how to make lots of hydrogen. But typically the process involves consuming natural gas. If we’re going to use hydrogen to sustainably decarbonize the world, we need to take fossil fuels out of the equation.

One of the best ways to do this would be to split water, which involves breaking H~2~O into its constituent elements—hydrogen and oxygen—using large amounts of electricity or heat. But splitting water at scale requires a tremendous amount of energy, and since the world still mostly runs on fossil fuels, they often end up providing the power. To foster a sustainable hydrogen economy, a 2017 Department of Energy report called for water splitting efforts to be fueled by renewable power like wind and solar. The report also floated the idea of using heat from advanced nuclear reactors to increase America’s hydrogen production without further contributing to climate change.

But creating a giant hydrogen supply won’t do much good unless there’s a way to use it. Today, car manufacturers are developing hydrogen fuel cells, so that when the hydrogen economy finally arrives, they’ll be ready to take advantage of it. Yet for now, no one wants to buy a hydrogen-powered car because there isn’t a ready supply of hydrogen fuel. It’s a sort of chicken-and-egg problem. The Earth Fund could end the stalemate by pledging to rapidly scale up sustainable hydrogen production, finally giving the hydrogen fuel cell industry the supply it needs.

Time is the enemy in a rapidly warming world, and it’s imperative to decarbonize our energy as fast as possible. If Bezos invested just a small fraction of the Earth Fund into these climate technologies, it would dramatically accelerate their deployment. But if technology is a salve, it can also be a poison. According to Amazon’s own statistics, the company pumps 44 million tons of carbon into the air each year from its delivery vehicles, data centers, and other indirect sources—far more than Microsoft, Google, or Apple. If Bezos really wants to fight climate change, his own company may be the best place to start.