HRAUN/Getty Images

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The world can still hope to stave off the worst ravages of climate breakdown but only through a “now or never” dash to a low-carbon economy and society, scientists have said in what is in effect a final warning for governments on the climate.

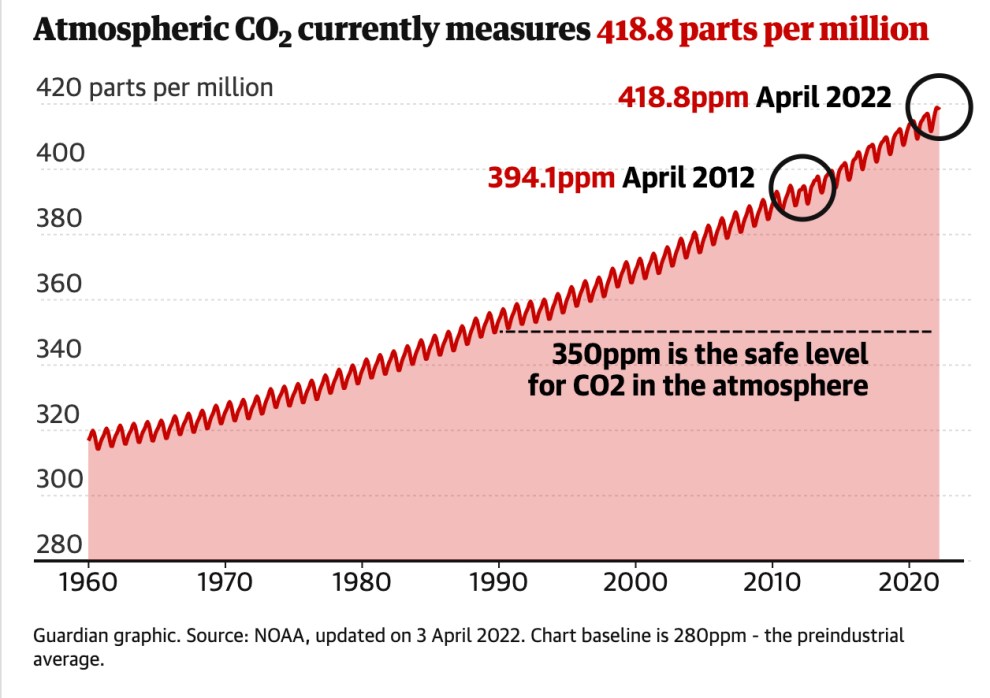

Greenhouse gas emissions must peak by 2025, and can be nearly halved this decade, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), to give the world a chance of limiting future heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The final cost of doing so will be minimal, amounting to just a few percent of global GDP by mid-century, though it will require a massive effort by governments, businesses and individuals.

But the chances were narrow and the world was failing to make the changes needed, the body of the world’s leading climate scientists warned. Temperatures will soar to more than 3 C, with catastrophic consequences, unless policies and actions are urgently strengthened.

Jim Skea, a professor at Imperial College London and co-chair of the working group behind the report, said: “It’s now or never, if we want to limit global warming to 1.5 C. Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible.”

The report on Monday was the third and final section of the IPCC’s latest comprehensive review of climate science, drawing on the work of thousands of scientists. IPCC reports take about seven years to compile, making this potentially the last warning before the world is set irrevocably on a path to climate breakdown.

Though the report found it was now “almost inevitable” that temperatures would rise above 1.5 C—the level above which many of the effects of climate breakdown will become irreversible—the IPCC said it could be possible to bring them back down below the critical level by the end of this century. But doing so could require technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which campaigners warned were unproven and could not be a substitute for deep emissions cuts now.

The UN secretary general, António Guterres, said some governments and businesses were “lying” in claiming to be on track for 1.5 C. In a strongly worded rebuke, he warned: “Some government and business leaders are saying one thing—but doing another. Simply put, they are lying. And the results will be catastrophic.”

Soaring energy prices and the war in Ukraine have prompted governments to rethink their energy policies. Many countries—including the US, the UK and the EU—are considering ramping up fossil fuels as part of their response, but the IPCC report made clear that increasing fossil fuels would put the 1.5 C target beyond reach.

Guterres said: “Inflation is rising, and the war in Ukraine is causing food and energy prices to skyrocket. But increasing fossil fuel production will only make matters worse.”

John Kerry, the US special presidential envoy for climate, called the report “a defining moment for our planet” and warned governments must move faster. “The report tells us that we are currently falling short in our battle to avoid the worst consequences of the climate crisis and mobilize the urgent global action needed. But importantly, the report also tells us we have the tools we need to reach our goals, cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030, reach net zero by 2050, and secure a healthier, cleaner planet,” he said.

The IPCC working group 3 report found:

- Coal must be effectively phased out if the world is to stay within 1.5 C, and currently planned new fossil fuel infrastructure would cause the world to exceed 1.5 C.

- Methane emissions must be reduced by a third.

- Growing forests and preserving soils will be necessary, but tree-planting cannot do enough to compensate for continued emissions for fossil fuels.

- Investment in the shift to a low-carbon world is about six times lower than it needs to be.

- All sectors of the global economy, from energy and transport to buildings and food, must change dramatically and rapidly, and new technologies including hydrogen fuel and carbon capture and storage will be needed.

Pete Smith, a professor of soils and global change at Aberdeen University, said: “The time of reckoning is now. We have one decade to get on track. We use fossil fuels in all these things that we need to change.”

Poor countries warned they were ill-equipped to make the changes needed and required financial assistance from richer nations to cut emissions and help them adapt to the impacts of the climate crisis. Madeleine Diouf Sarr, the chair of the least developed countries group at the UN climate talks, said: “There can be no new fossil fuel infrastructure. The emissions from existing and planned infrastructure alone are higher than scenarios consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 C with no or limited overshoot. We cannot afford to lock in the use of fossil fuels.”

Catherine Mitchell, a professor emerita of energy policy at Exeter University, said the needs of the poorest countries must be prioritized. “Unless we have social justice, there are not going to be more accelerated greenhouse gas reductions. These issues are tied together.”

Publication of the report was delayed by a few hours as governments wrangled with scientists in marathon sessions, culminating late on Sunday night, over the final messages in the 63-page summary for policymakers. While IPCC reports are led by scientists, governments have input on the final messages in the summary for policymakers.

The Guardian understands that governments including India, Saudi Arabia and China questioned messages including on financing emissions reductions in the developing world and phasing out fossil fuels. However, scientists stressed that the final summary was agreed by all 195 governments.

This was the third installment of the IPCC’s sixth assessment report, covering ways of reducing emissions. It follows a first section published last August that warned human changes to the climate were becoming irreversible; and a second section published at the end of February warning of catastrophic impacts.