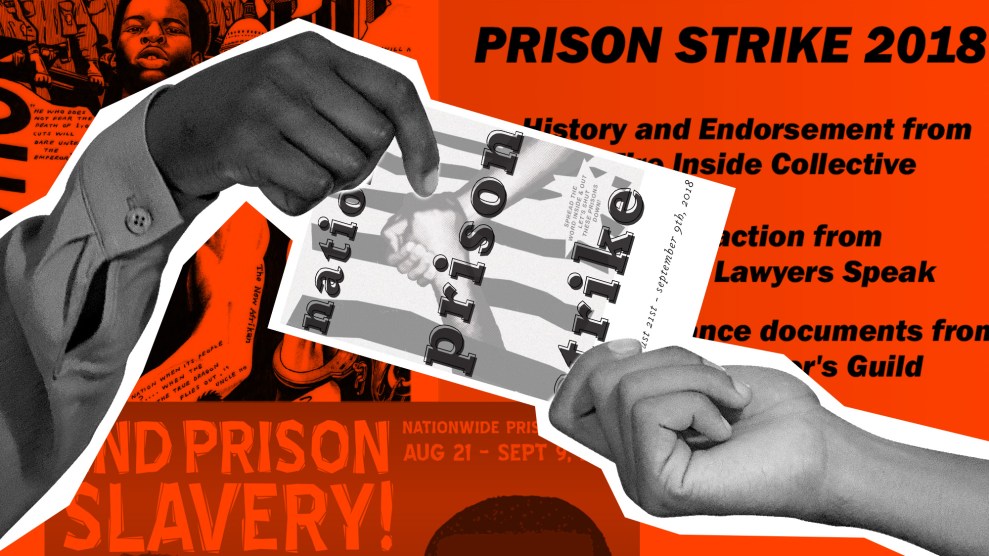

Mother Jones illustration; Getty; incarceratedworkers.org

One recent afternoon in a pizzeria in Oakland, California, Cole Dorsey pulls out an LG flip phone to explain how he’s helping organize a strike in the country’s harshest workplace. The phone is small and black, with a busted interior screen. Occasionally, he says, the cover lights up with a Texas area code and a number associated with Global Tel Link, which means a prisoner is calling. When the calls come in, Dorsey picks up, takes a message, then hangs up and waits for the phone to ring again. Then he passes the original message along to an inmate held in another part of the same facility.

Dorsey’s makeshift messaging system connects prisoners who may be separated from each other by just a few hundred feet, as well as walls, fences, and rules that prevent them from congregating. The prisoners are members of the Industrial Workers of the World, the militant union that is backing a prison strike that’s set to begin this week. Starting on August 21, prisoners in at least 17 states are expected to refuse to go to work, launch sit-ins in common areas, boycott commissaries, or go on hunger strike, according to Dorsey, an electrical lineman who’s a member of the IWW’s Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee. Since the strike was first announced in April, its imprisoned organizers have struggled to coordinate with each other and the thousands of prisoners they hope will join their protest. They’ve often relied on the IWOC and outside activists like Dorsey who have found creative ways to get messages into the black box of the prison system.

News of the strike has spread via a network of contraband cell phones and by word of mouth as inmates are transferred from prison to prison, says Brooke Terpstra, another IWOC organizer. Word has also traveled through the mail, in publications like the prisoner-oriented San Francisco Bay View, and in newsletters like Solid Black Fist, which is assembled and mailed to inmates by a 23-year-old college radio host turned prison abolitionist in Seattle. One newsletter discussing related protests seems to have slipped past prison censors by topping its screeds on struggle and solidarity with innocuous headlines like “It’s Winter!” and “Researcher Studies Communication in Prairie Dog Communities.”

This year’s strike is a successor to the 2016 work stoppage that generated headlines as the largest prison strike in US history. The protest, which lasted more than a month in some facilities, was meant to draw attention to prison labor, which organizers argued amounts to modern slavery. Inmate laborers are often paid just cents on the hour (or nothing at all, in Arkansas, Georgia, and Texas) for doing mandatory cooking, cleaning, and maintenance jobs or working for companies like AT&T and McDonald’s. (While the 13th Amendment bans slavery, it allows involuntary servitude “as a punishment for crime.”)

Organizers still don’t know how many prisoners joined in the 2016 strike, though they say prisons in about a dozen states locked down 30,000 inmates in response to protests. Unrest inside prisons is always difficult to verify; officials in Alabama, Michigan, and Florida confirmed work stoppages at the time, while others in Texas and South Carolina denied them despite published accounts.

This year’s strike, which is intended to start on Tuesday and last until September 9, originated with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, an anonymous collective of inmates who provide legal services to other prisoners. The group, which appears to be active in multiple states (organizers won’t reveal the exact number) posted a press release about the strike on its Twitter account, one of several social-media accounts it manages to control from behind bars. (The account gives its location as “Hell on Earth.”)

Jailhouse Lawyers Speak had intended to wait another year to call another national strike, Terpstra says, but it decided to act sooner after a bloody riot in South Carolina’s Lee Correctional Institution in April. Seven prisoners were stabbed to death during the seven-hour riot, which corrections officials quickly blamed on a gang dispute over cellphones and territory. But historian Heather Ann Thompson, who wrote a Pulitzer-winning book about the 1971 Attica prison uprising, reported in the New York Times that the riot was sparked by prison conditions and was made worse by officials’ failure to get the situation under control. “Yes, it was a gang fight, prisoners tell me, but it was corrections officials who had decided to house rival gangs in the same dormitory, and it was the officials’ increasingly punitive policies that exacerbated tensions on the inside,” Thompson wrote.

Describing the Lee riot as a “senseless uprising” caused by a lack of respect for prisoners’ lives, Jailhouse Lawyers Speak called for a strike and listed 10 demands including voting rights for all inmates and former felons and ending life sentences without parole. It also has specific policy goals, like reinstating Pell grants for prisoners and repealing the Prison Litigation Reform Act, which makes it harder for inmates to sue over poor living conditions.

“Most of the demands are not actionable items that prison authorities are able to grant,” explains a zine distributed by the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee. “The goal is not to hold out and win negotiations with officials, but to last those 19 days and punch the issue to the top of the political consciousness and agenda.”

Terpstra says the strike is meant not just to increase awareness of prisoners’ demands, but also to promote a ceasefire between prison gangs by giving them a common goal—much as gangs cooperated during the 30,000-person hunger strike protesting solitary confinement in California prisons in 2013. Dorsey says Jailhouse Lawyers Speak also hoped to ally with other left-wing political groups. A few chapters of the Democratic Socialists of America have endorsed the protest.

“The question has been asked, ‘Are prison protests effective’ ? Of course they are,” Jailhouse Lawyers Speak said in a statement on August 9. “Today, we have college professors and lawmakers discussing prison ‘slavery.’ As prisoners, we may not get the immediate relief we desire, but the effect of our resistance builds up as it reverberates.”

Prison officials have begun to restrict inmate mail and access to phones, says King Downing, a member of the National Lawyers Guild, which has supported the strike effort since 2016. Organizers say some prisons have already isolated suspected strike leaders. Last month, the Virginia Department of Corrections moved Kevin Rashid Johnson, a member of the New Afrikan Black Panther Party, to Sussex State Prison in what his supporters say was an act of retaliation. Also in July, IWOC reported that Siddique Hasan had been put in solitary confinement in the Ohio State Penitentiary for talking about the upcoming protest. (Hasan was sentenced to death for participating in a 1993 prison uprising that resulted in the deaths of nine inmates and a guard.) Neither the Virginia nor Ohio corrections departments responded to questions about Johnson or Hasan. In preparation for potential crackdowns, IWOC has sent prisoners affidavit forms they can use to report violations of their rights.

“Prisoners are taking a huge risk,” says Amani Sawari, who publishes Solid Black Fist. “They know they could lose potentially their jobs, their privilege status, their recreation programs, their lives as a result of choosing to strike.”

Dorsey admits that when the strike begins on August 21, he and other outside organizers may know nothing about what, if anything, is happening behind bars. “There will be a blackout,” he predicts. In the meantime, he’s trying to protect the other members of the IWW—the group that gave him a lifeline, job training, and way out of Michigan after his release from prison 12 years ago. “I feel privileged to be a part of it,” says Dorsey. “Life goes on for us on the outside, as much as, when we’re locked up, we wish it didn’t.” For organizers on the inside, he says, planning the protest is a way to feel powerful, “to recognize that people care about what you think, even though you’re going to be there for maybe the rest of your life.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified the name of the newsletter Solid Black Fist.