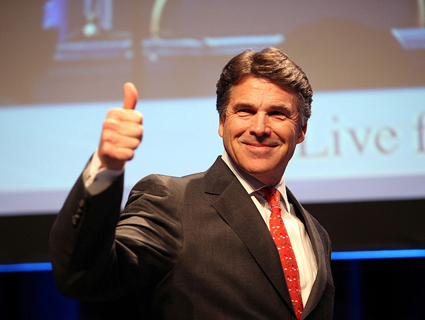

Flickr: Gage Skidmore

Texas Governor Rick Perry’s close relationship with fringe figures of the religious right is likely to be an issue for him if, as looks increasingly likely, he decides to run for president. But his central role in an international incident could loom even larger. Last night, he declined to intervene in the execution of a Mexican national, Humberto Leal, by lethal injection, despite public requests from the White House and the government of Mexico to hold off. Here’s the AP:

A Mexican national was executed Thursday evening for the rape-slaying of a San Antonio teenager after the U.S. Supreme Court turned down a White House-supported appeal to spare him in a death-penalty case where Texas justice triumphed over international treaty concerns…Police never told Leal after his arrest that he could seek legal assistance from the Mexican government under an international treaty, and his case had prompted appeals on what it could mean for other foreigners arrested in the United States and for Americans detained abroad. His appeals lawyers said such assistance would have helped his defense.

Perry’s death penalty record is the sort of thing that, in a normal political climate (as opposed to the current one), would cripple any realistic shot at the Oval Office. He refused to stay the execution of Cameron Todd Willingham, and, after the fact, when the evidence began to overwhelmingly suggest that Willingham had been innocent, he replaced three members of the commission that had been reviewing the case. (Perry stands by the execution, insisting that Willingham was a “monster.”) After two decades on death row, Anthony Graves was released only after a lengthy investigation from Texas Monthly showed that he had been wrongfully convicted. And Perry’s doggedly embraced the death penalty even as studies continue to show that executions are costing his cash-strapped state hundreds of millions of dollars.

Perry has presided over more than 230 executions as governor. As the Texas Tribune notes, he’s commuted the death sentences of 31 death row inmates, but in 30 of those cases, that was only because the Supreme Court ordered him to. The high court intervened against again last March, ordering that the state was required to consider DNA testing in an appeal from a death row inmate. In 2010, a Houston district judge ruled the state’s death penalty system was unconstitutional because it violated the 8th and 14th Amendments. Earlier this year, a Texas House committee considered a bill to put a two-year moratorium on executions, in light of continued evidence of wrongful convictions. And in April, a psychologist frequently employed as an expert by the state in death penalty cases was banned from performing mental evaluations after she was found to be using “unscientific” methods in her official analyses. Through it all, Perry has maintained the same confident tone: “I think our system works.”

The Leal execution is about more than just criminal justice. It also speaks to Perry’s hostile relationship with Washington, which is at the root of his appeal to the tea party. He’s clashed with Obama over perceived slights in disaster-relief funding and border security (although Texas has grown fat off border pork). Now, Perry’s returning the favor: The White House told the governor his decision would put Americans at risk when they travel abroad; Perry decided that wasn’t his problem. As with his suggestion in 2009 that Texas could secede from the Union over Obama’s policies, it’s a case of Perry demonstrating less than total allegiance to the national interest. Is that presidential? That’s for voters to decide.