Update: The Supreme Court has ruled that foreign plaintiffs in most cases do not have standing to sue U.S. corporations over human-rights violations in American courts. The decision (PDF) came in a case, Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, involving allegations that Shell was complicit in human-rights abuses in Nigeria. It is expected that other companies will move for dismissal of similar suits over human-rights violations overseas, including the Exxon case we investigate in this story.

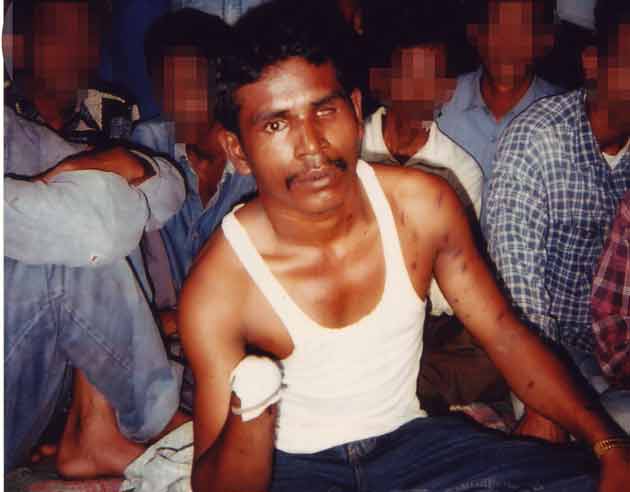

Even in the dry legalese of a court complaint, the account of John Doe III is not for the faint of heart:

In the summer of 2000, soldiers detained him while he was visiting a refugee camp. They shot him “in three places on his leg,” then “tortured him for several hours.” The soldiers “broke his kneecap, smashed his skull, and burned him with cigarettes.” After he was taken to a hospital to treat his wounds, he was returned to this captors, who held him for roughly a month and “tortured him regularly.”

This was the Aceh Province, Sumatra, Indonesia, at the height of a bloody civil war. Such accounts were commonplace. But in this case, according to the complaint, the man’s captors were not just any soldiers. They were “ExxonMobil security personnel.” And now, more than a decade later, ExxonMobil has been ordered to stand trial in a human rights lawsuit.

In June 2001, John Doe III and 10 other civilian neighbors of ExxonMobil’s Arun natural gas facility filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil in federal district court in Washington, DC. In John Doe v. ExxonMobil, (PDF) the villagers charge the company with complicity in torture, arbitrary detention, and extrajudicial killings allegedly committed by Indonesian soldiers it hired to provide security.

ExxonMobil has steadfastly maintained its innocence in the case.

“We have fought the baseless claims for many years,” said ExxonMobil spokesman David Eglinton. “The plaintiffs’ claims are without merit. While conducting its business in Indonesia, ExxonMobil has worked for generations to improve the quality of life in Aceh through employment of local workers, provision of health services and extensive community investment. The company strongly condemns human rights violations in any form.”

But in a 2008 ruling (PDF), federal district court judge Louis Oberdorfer ordered Exxon to face trial. “A reasonable finder of fact,” the judge wrote, citing internal correspondence from Exxon and its Indonesian subsidiary, EMOI, “could conclude that the paid security forces committed the alleged torts and that EMOI and Exxon Mobil are liable.” Exxon appealed, but a federal circuit court panel upheld that part of the ruling in July 2011.

The fate of the ExxonMobil case now rests in the hands of the US Supreme Court. On October 1, the court heard arguments in a similar, better-known case, Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum (Shell)—and it’s that case that may determine whether the Acehnese villagers ever get their day in federal court.

Like John Doe v. ExxonMobil, the Kiobel case relies on an 18th-century statute called the Alien Tort Claims Act. The Nigerian plaintiffs say it gives citizens outside the United States the right to sue any corporation with a US presence for aiding and abetting human rights abuses—such as the Nigerian government’s alleged extrajudicial killings of Ogoni protester Ken Saro-Wiwa and Barinem Kiobel.

Like ExxonMobil, Shell says the Alien Tort Statute does not apply to cases like this: that only individuals—and not corporations—can be held liable for human rights violations on foreign soil.

Expected as early as December, the court’s ruling will almost certainly set a major precedent—either allowing people around the world to continue suing companies in US federal court for abuses like slave labor, extrajudicial killings, and torture, or shutting them out for good. More than a dozen Alien Tort cases involving hundreds of plaintiffs are riding on the decision. They target corporations from Chevron to Chiquita.

Kiobel‘s significance has not escaped the attention of industry associations like the Product Liability Advisory Council, a nonprofit group representing more than 100 manufacturers in the US and abroad, which has tracked cases brought under the Alien Tort Statute. “The number of ATS claims naming corporate defendants has risen steadily in recent years,” the Council told the Supreme Court in a brief on Shell’s behalf. “ATS cases impose substantial litigation costs.” What’s more, the brief says, “[b]eing accused of genocide in federal court causes significant reputational harm, regardless of the actual merits of the allegations.”

Ilya Shapiro of the Cato Institute, a conservative think tank, who authored an amicus brief in the case supporting Shell, says it often costs a corporation less to settle than to defend itself, creating an incentive for false accusations: “If the Court finds that federal courts do have jurisdiction over these types of claims,” he said in an email, “it will be an invitation to sue for anything anywhere. We would internationalize the extortion-by-trial-lawyer problems we have in America.”

But proponents of the Alien Tort statute say that if a corporation doing business in this country does indeed aid and abet abuses abroad, it belongs in US federal court. They point out that courts in the host countries often cannot adequately handle such cases, leaving plaintiffs no other forum.

Terry Collingsworth, a human rights lawyer who originally filed the Aceh case and remains co-counsel on it, says he objects when companies claim they shouldn’t be sued under the Alien Tort law. Because they prohibit the very same transgressions in their own voluntary codes, he says, they should also be prepared to stand in a court of law “and be held responsible for murder and torture.”

Rather than opposing the Alien Tort Statute, says Peter Weiss, a civil rights lawyer who pioneered the modern use of the statute in the 1970s, corporations should welcome it. “[The law] is being used to make their competitors in foreign countries hue to a universal standard of human rights,” he says. “ATS has served as an important instrument in enforcing human rights.”

On the morning of March 21, 2001, a doorbell rang on the ninth floor of a run-down building in Washington, DC, at the International Labor Rights Forum, an advocacy group for workers affected by economic globalism. At the dingy pressed-wood door a young foreigner appeared speaking no English, only the Indonesian language of Bahasa.

His name was Mohammed Saleh, and he was a student activist representing a small human rights group in Aceh, Indonesia. The Indonesian government had recently imprisoned the group’s leader, Muhammad Nazar, for advocating a referendum on Aceh independence. So Nazar arranged to send Saleh to Washington, DC, to tell Americans about Aceh’s crisis.

One of the Forum’s staffers, Bama Athreya, who happened to have learned Bahasa while working in Jakarta, welcomed the visitor. She had met him earlier and he’d told her the stories relayed by villagers living near ExxonMobil—people like John Doe III. The two of them seized on an idea: Burmese villagers had recently used US courts to sue an oil company, UNOCAL, over complicity in slave labor. The case was being colitigated by Athreya’s boss at the International Labor Rights Forum, Terry Collingsworth. Could something like that work in Aceh?

Up on the 9th floor, Athreya introduced Saleh to Collingsworth. The son of a shop steward at a copper mill in Cleveland and a former machine operator at the mill, Collingsworth grew up wanting to be a labor lawyer. In law school he developed an interest in human-rights issues, and at 32, cofounded the International Labor Rights Forum. The UNOCAL case was one of organization’s first major cases.

The Forum litigated for fair and humane working conditions at multinationals worldwide, aiming to ensure that workers “weren’t getting led to slaughter.” That kind of work, as Collingsworth saw it, also protected US workers because the more corporations could act with impunity overseas, the more incentive they’d have to shift jobs out of the United States. “The global economy,” he says, “is extremely relevant to an American worker and citizen. Our quality of life is going to be dictated by what corporations can get away with in the rest of the world.”

When Saleh arrived, Collingsworth took him to a conference room. With Athreya translating, he listened to the young man’s account of the atrocities in Aceh, and the alleged role of ExxonMobil’s security force. Within a week, he was on a plane to Indonesia.

Located on the northern tip of the island of Sumatra, one of the larger islands in the archipelago of Indonesia, Aceh is a largely undeveloped tropical province known for its rice fields, palm plantations, and the devastating 2004 tsunami. But Aceh is also a center of deep Islamic faith and fierce independence. For more than 400 years the area was an Islamic sultanate with deep cultural and trading ties to India and the Middle East. The Dutch tried to colonize it in the 1870s; Japanese occupiers came in during World War II. But the recent tensions result from a historical rivalry with the neighboring island of Java. When Indonesia became a nation in 1949, Java rose in status, with its largest city, Jakarta, as the capital.

A rice farmer hoes her crop in front of the ExxonMobil facility in Lhoksukon, Aceh. Emily JohnsonIndonesia’s nationalist leaders dangled promises of autonomy to enlist Aceh’s cooperation, but those promises went nowhere. The Acehnese chafed under the Jakarta-based regime—especially under Suharto, Indonesia’s second president, who took office in 1968.

A rice farmer hoes her crop in front of the ExxonMobil facility in Lhoksukon, Aceh. Emily JohnsonIndonesia’s nationalist leaders dangled promises of autonomy to enlist Aceh’s cooperation, but those promises went nowhere. The Acehnese chafed under the Jakarta-based regime—especially under Suharto, Indonesia’s second president, who took office in 1968.

Shortly after Suharto gained control, Mobil Oil began drilling for natural gas in Sumatra and in 1971 it discovered an enormous natural gas field in Aceh. Mobil contracted with Suharto’s government to extract gas from the field, forming a joint venture with the state petroleum company to process the gas. Under terms of the deal, the Indonesian government owned 55 percent of the facility, known as Arun, ExxonMobil 35 percent, and a Japanese company 10 percent.

By the late 1970s, the Arun project was producing a dizzying volume of liquid natural gas. The arrangement began to generate hundreds of millions of dollars in profits for Mobil and its Indonesian state-owned partner, Pertamina. Little of that money was invested back into the region. By the mid-’70s, a movement for Acehnese independence known as GAM—Geraken Aceh Merdeka, or Free Aceh Movement—emerged, and its leaders demanded that more of Mobil’s revenue go to poverty-stricken Aceh. The demand did not go over well in Jakarta.

Crushed and forced into hiding, GAM turned to Libya for training in the late 1980s. The Indonesian military, later known as TNI, responded with a vicious crackdown beginning in 1989. Over the next decade the military presence made it difficult to monitor and record abuses, although the US State Department was reporting an increasingly alarming tally in the run-up to Suharto’s resignation in 1998. During a brief respite following the resignation, researchers for human rights NGOs and the Indonesian government documented a decade of atrocities committed against GAM and its perceived supporters.

But from 1999 to 2004 the repression returned, involving far more troops. While GAM itself has also been accused of intimidation, extortion, and human rights abuses, it is widely reported that the Indonesian military committed the majority of violence against civilians, mostly poor farmers like John Doe III.

In Indonesia, as in Colombia and Nigeria, national soldiers can double as private security forces for a price. “From the inception of the Arun Project,” says the John Doe complaint, referring to an agreement it says Mobil signed and included in the merger, “ExxonMobil has employed or otherwise retained members of the Indonesian military to provide security services for its facilities and operations in Aceh province…”

This mass grave was uncovered in central Aceh, the province where a bloody civil war raged for years. Jacqueline Koch, epa/CorbisThe complaint cites a 2001 Bloomberg News story reporting that “Exxon Mobil, by all accounts, became far too cozy with the Indonesian military during the Suharto years. It paid the salaries of the troops that guarded its fields and the nearby P.T. Arun liquefaction plant; it shared equipment the army apparently could not afford.”

This mass grave was uncovered in central Aceh, the province where a bloody civil war raged for years. Jacqueline Koch, epa/CorbisThe complaint cites a 2001 Bloomberg News story reporting that “Exxon Mobil, by all accounts, became far too cozy with the Indonesian military during the Suharto years. It paid the salaries of the troops that guarded its fields and the nearby P.T. Arun liquefaction plant; it shared equipment the army apparently could not afford.”

Before Mobil merged with Exxon in 1999, the facility produced 25 percent of Mobil’s entire worldwide oil and gas revenues. One ExxonMobil executive described Arun to the Wall Street Journal as “the jewel in the company’s crown.”

But by 2000, the jewel was under threat. GAM and other groups began abducting and attacking ExxonMobil employees. According to the lawsuit, ExxonMobil paid Indonesia’s soldiers $500,000 a month to protect the plant that year. But the violence continued, and ExxonMobil grew increasingly concerned.

Civilians remained in the crossfire throughout Aceh, and the area surrounding ExxonMobil’s Arun facility was no exception. In 1998, a coalition of 17 human rights organizations accused Mobil of providing material support to the army, including bulldozers and other equipment used to dig mass graves. A 1998 BusinessWeek article quoted eyewitnesses to summary executions and the use of Mobil equipment to cover them up; Mobil denied any knowledge of this, saying it had loaned excavators to the army but only for peaceful purposes. Three years later, an August 2001 article in Time‘s Asia edition reported that in Aceh “people literally line up to tell stories of abused and murders committed by the troops they call Exxon’s army.”

Then came the 2004 tsunami, which took more than 100,000 lives and prompted the warring parties to agree on Aceh’s autonomy and sign the 1995 Helsinki peace accord. The pact set up a human rights court, but Indonesian legislators explicitly forbade it from considering human rights allegations before 2006. So at the time, only Collingsworth’s plaintiffs were left to redress the atrocities of Aceh’s civil war.

Collingsworth’s plane landed in the city of Banda Aceh in late March of 2001, just as ExxonMobil was temporarily closing the Arun facility following a rise in attacks on the company’s employees and property. The Indonesian military was preparing to send 3,000 additional troops to the area, and a crackdown on civilians was going on unabated. Collingsworth had arrived in a war zone.

He immediately went to the prison to see Nazar, an Amnesty International prisoner of conscience. He found him on a bench in the prison courtyard. The local guards, who seemed sympathize with his cause, stood respectfully by.

Through a translator, Nazar grilled the visitor: Would the chances of succeeding with the lawsuit justify the high risks? How could Collingsworth avoid violent retaliation against Nazar’s staff and the plaintiffs? Collingsworth answered questions for several hours, and Nazar finally gestured approval to the translator, saying Collingsworth should be taken to meet the alleged victims.

Outside the Exxon facility in Lhoksukon, Aceh. Emily JohnsonOn the ride southbound to ExxonMobil’s sprawling facility in Lhokseumawe, Collingsworth and his fellow passengers passed a series of armed military checkpoints, he says. The two Acehnese on the trip—the translator and a Nazar associate—told the soldiers they were showing their visitors around and taking them to the beach. They avoided the area immediately around the Arun facility, where Indonesian troops guarded the main gas pipeline and sprawling gas complex.

Outside the Exxon facility in Lhoksukon, Aceh. Emily JohnsonOn the ride southbound to ExxonMobil’s sprawling facility in Lhokseumawe, Collingsworth and his fellow passengers passed a series of armed military checkpoints, he says. The two Acehnese on the trip—the translator and a Nazar associate—told the soldiers they were showing their visitors around and taking them to the beach. They avoided the area immediately around the Arun facility, where Indonesian troops guarded the main gas pipeline and sprawling gas complex.

Instead, the group convened a considerable distance away in a quiet gazebo in a public park. They wanted the “safety of sunshine,” Collingsworth says—an open-air meeting to disarm suspicion and reduce chances of a sneak attack, especially with witnesses present. In the course of eight hours, Collingsworth heard from about 50 people. Determining who could remain safe from reprisals and who had suffered explicitly from ExxonMobil’s unit specifically, he came up with a list of 11 plaintiffs.

Two months later, on June 19, 2001, Collingsworth filed the suit in district court in Washington, DC.

In John Doe v. ExxonMobil, the alleged incidents date from 1999 to 2001, one of the most intense periods of violence in the Aceh civil war:

- “A member of ExxonMobil’s security personnel” forced his way into the home of a pregnant female, wielded a rifle, “threatened to kill her and her unborn child with his gun, then beat and sexually assaulted her.”

- “ExxonMobil security personnel” accosted a man traveling between villages, beat him, handcuffed him, accused him of membership in GAM, ignored his denial, and “took him to Post A-13 on ExxonMobil’s property,” where they threw him to the ground, wielded a knife, and “carved the letters ‘GAM’ into his back…regularly torturing him” for several more weeks.

- “ExxonMobil security personnel” stopped a villager riding his motorcycle, beat him severely on his head and body, tied his hands, blindfolded him, took him to a military camp, kept the blindfold on him for three months, and tortured him regularly, “using electricity all over his body, including his genitals.”

In an email, ExxonMobil’s Eglinton declined to answer additional questions about ExxonMobil’s view of ATS suits in general, its method of dealing with security challenges abroad. He also declined to comment on the specifics of the Aceh lawsuit.

But Martin Weinstein, partner at the powerful DC law firm Wilkie, Farr, & Gallagher LLP and Exxon’s chief legal spokesperson for much of the case, told an interviewer with Public Radio International’s The World in 2002 that “we have no knowledge of any of these abuses taking place around the facilities. We condemn them if they did occur, but don’t know whether the occurred or not.”

While documents in the case are sealed, Judge Oberdorfer’s 2008 court ruling quotes the material—including ExxonMobil’s internal correspondence.

Oberdorfer cited no evidence that ExxonMobil knew about any specific incident alleged in the suit, much less condoned or authorized them. But he wrote that the evidence did indicate that company at the very least should have known about the Indonesian soldiers’ tendencies.

Oberdorfer points out that one ExxonMobil email noted “the poor reputation of the Indonesian military, especially in the area of respecting human rights.” Another internal company report cited a news report that “armed security forces of EMOI”— the company’s own paid agents—”…conducted security sweeping operations at five villages near the explosive storage of ExxonMobil” and “that thousands of people were threatened due to sweeping operations and gunfire.”

“Here,” the judge stated, “a finder of fact could reasonably conclude that EMOI was negligent in hiring—or at least in retaining—its paid security forces. There is sufficient evidence that EMOI should have known that the military security posed undue risks to local Indonesians near its Arun gas venture.”

Also in the PRI interview, Weinstein said that “the government has responsibility for security,” underscoring ExxonMobil’s argument that Indonesia required the company to hire the troops.

But Oberdorfer was not convinced. According to the contract he cited between ExxonMobil and Indonesia’s state-owned oil company, Pertamina, Pertamina agreed to “assist and expedite (EMOI)’s execution of” gas extraction and production “by providing…security protection…as may be requested by (EMOI)…”

Oberdorfer pointed to evidence that ExxonMobil initiated that request.

“In December 1999,” Oberdorfer wrote, “Robert Haines—Exxon Mobil’s Manager of International Government Affairs—sent a memorandum to Mobil’s CEO, reporting on his meeting in Indonesia with subordinates to discuss the security concerns in Aceh.” Haines said ExxonMobil “has asked for the assistance of the military to protect its facilities.”

Oberdorfer said that even if the contract had required that ExxonMobil hire the troops, it doesn’t absolve them of responsibility for their alleged actions. “Is the owner of a swimming pool insulated from liability per se for a lifeguard’s negligence,” the judge asked, “simply because the lifeguard is required to be there? Surely not.”

Finally, Weinstein pointed out that “there is no allegation that ExxonMobil…directed in any way, shape, or form, any of these abuses,” but this did not address the lawsuit’s principal contention about liability: that the company exercised some direction over the troops—for which the judge agreed Exxon could be liable. “A fact finder could reasonably conclude that EMOI had sufficient control over and, effectively ‘managed’ the security forces,” the 2008 ruling notes, “to create a master-servant relationship.”

The judge found that this relationship is suggested throughout the materials. He quotes one internal email stating “it(‘)s not going to be easy managing 900 troops in our operational area.” Another official deposed in the case said security managers at the subsidiary often went “up the chain and request(ed) additional corporate kinds of support” from ExxonMobil officials in the United States.

In short, the judge found sufficient evidence of the company’s control to permit a jury to consider its liability.

A spirited exchange between opposing lawyers in 2008 succinctly boiled down the case:

“ExxonMobil is innocent,” Theodore Wells, Exxon’s outside counsel, offered in summary. “What took place…relates to the activities of the Indonesian government and the Indonesian military…and we have no dog in that race.”

Michael Hausfield, part of the plaintiff’s legal team, sprang from his chair to offer his rebuttal: “Exxon fed the dog, they clothed the dog, they housed the dog, and they paid the dog. Let’s bring the dog on.”

The judge consented, ordering the case to trial. Oberdorfer didn’t give the plaintiffs everything they wanted. He dismissed the Alien Tort charges, allowing only related tort claims in state court. It was the appeals court that restored the Alien Tort claims in 2011. But he agreed that ExxonMobil should face the villagers in a courtroom: “Plaintiffs have provided sufficient evidence, at this stage, for their allegations of serious abuse.”

A sign warns civilians to keep out of the first of four natural gas fields that together make up ExxonMobil’s facility in Lhoksukon, Aceh. Emily JohnsonExxonMobil is the largest oil company in the world, and consistently one of the most profitable, netting $41 billion in 2011. The lion’s share of those earnings come from operations outside US boundaries, in more than 200 countries—including places like Aceh, Equatorial Guinea, Chad, and Nigeria, “where risk is endemic,” says Steve Coll, president of the New America Foundation and the author of Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power. “You might think rationally there is no reason for them to be there, given the risks and reputational costs and just the general misery.” But because the company’s investors want to see sizable reserves for the future, ExxonMobil “can’t afford to give up any chunk of 200,000 or 300,000 barrels a day that they can reasonably produce,” Coll says. “They can’t afford to shrink.”

A sign warns civilians to keep out of the first of four natural gas fields that together make up ExxonMobil’s facility in Lhoksukon, Aceh. Emily JohnsonExxonMobil is the largest oil company in the world, and consistently one of the most profitable, netting $41 billion in 2011. The lion’s share of those earnings come from operations outside US boundaries, in more than 200 countries—including places like Aceh, Equatorial Guinea, Chad, and Nigeria, “where risk is endemic,” says Steve Coll, president of the New America Foundation and the author of Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power. “You might think rationally there is no reason for them to be there, given the risks and reputational costs and just the general misery.” But because the company’s investors want to see sizable reserves for the future, ExxonMobil “can’t afford to give up any chunk of 200,000 or 300,000 barrels a day that they can reasonably produce,” Coll says. “They can’t afford to shrink.”

Exxon “essentially bought the war when they bought Mobil,” Coll adds. “ExxonMobil prior to 2000 [had few] properties in conflict zones. They were a relatively risk-aversive company. It took a while…to come to terms with the complexity of their position.” In 2002, after initially resisting, the company signed on to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, which were initiated by NGOs, the US and British governments, and companies in the energy and extractive industries. The principles standardized security practices to encourage “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

While ExxonMobil doesn’t disclose its legal budget, the company maintains a sizable counsel staff and retains some of the most powerful law firms in the country. In one of the most famous lawsuits against it, about the 1989 Valdez spill, the company was ordered to pay $5 billion in punitive damages—but in five appeals over a dozen years, going all the way to the Supreme Court, it winnowed that amount to $500 million.

Few lawsuits are significant enough to make a dent in the company’s financial projections. In SEC filings from 2001 to 2011, a voluntary list of potential liabilities to inform investors, Exxon listed only 28 lawsuits against it. The Aceh suit is not included.

“The Corporation does not believe the ultimate outcome of any currently pending lawsuit against ExxonMobil,” the company’s 2011 annual report states, “will have a material adverse effect upon the Corporation’s operations, financial condition, or financial statements taken as a whole.”

Collingsworth’s case has attracted the support of like-minded NGO lawyers and pro bono firms, most notably the acclaimed human rights litigator Agnizeszka Fryszman of the DC firm Millstein & Cohen, now co-counsel. But at least in terms of resources, the odds are still in ExxonMobil’s favor: two NGO lawyers working on contingency for a dozen poor villagers and their families against a corporate in-house counsel office supplemented by three outside law firms.

“Exxon has a very aggressive strategy, and they have unlimited legal resources to execute it,” Fryszman says. “It’s basically to grind us into the dust.”

But the company maintains its innocence. “I have been with this case since day one, [and] I find these allegations…outrageous,” Paul W. Wright, ExxonMobil’s in-house counsel, told Judge Oberdorfer in a 2008 hearing. “I think it’s fair to expect that this company will vigorously defend itself through every stage of this case.”

Back in Aceh, the identity of the plaintiffs remains closely guarded. The lawyers have fought to ensure that any ExxonMobil cross-examination would protect their clients’ anonymity, and have restricted media access to their clients for fear of reprisal.

But the delays have already taken their toll. A few years into the court proceedings, Collingsworth reported that unknown assailants had killed two of his plaintiffs. The earliest a trial could take place is 2013—a full dozen years after the alleged events.

“They’re not in forgive and forget mode,” said Collingsworth, referring to the remaining plaintiffs, including relatives of the deceased. “Those who were tortured or had somebody killed suffered horrendous injury, and they’re in this for the long haul. This is their life now.”

In the jargon of the courts, ExxonMobil’s case is “stayed” until the US Supreme Court rules on Kiobel v. Shell—in legal limbo. During Monday’s hearing, lawyers addressed a basic question about one of the nation’s oldest laws.

When Congress enacted the Alien Tort Claims Act of 1789, occasionally violent US-based privateers were plying the seas in pursuit of black-market riches. The Alien Tort act gave foreign-born nationals the chance to file claims against the privateers in US federal court, which was deemed fairer and less parochial than regional or local courts. Dusted off by civil rights activists in the 1970s, the Alien Tort statute recently has come to apply to any corporations with a presence in the United States.

In a series of precedents over recent decades—including in the ExxonMobil case—lower courts have firmly established this principle. According to the Product Liability Advisory Council, plaintiffs have filed almost 250 Alien Tort cases over this period—nearly half of them against at least one corporate defendant. Courts dismissed many of the cases, but three have gone to trial, one resulting in a verdict for the plaintiffs, and a few others have settled. And now the trickle of cases shows signs of turning into a flood: Of the 120 cases against corporations, fully half were filed since 2008.

The Kiobel decision could change all that: While in previous cases the right of plaintiffs to sue in US federal courts for abuses committed overseas had gone unquestioned, the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals in Kiobel ruled that Shell was immune: that liability for human rights violations applies only to natural persons. This is the issue that dominated the first round of oral Kiobel arguments before the Supreme Court in February.

Monday’s arguments presented a new wrinkle. While exploring the United States’ role as “the court of last resort” for human rights abuses abroad, the court addressed whether the Alien Tort Statute applies to a foreign entity like Dutch/UK-based Shell, which also has operations in the United States. And while it’s risky business to predict the court’s intentions, the line of questioning seemed to hint at a compromise, according to knowledgeable observers from both sides: Aliens must first try to sue either in the country where the abuses took place, or in the country in which the corporation is based—and then demonstrate it was impossible to do either. Such ruling could dismiss Kiobel while leaving the ExxonMobil case intact—that is, if the court doesn’t rule for corporate immunity across the board.

In their private deliberations on corporate immunity, the justices will be facing a judicial dilemma of their own making. They ruled in the 2010 Citizens United case that corporations have the rights of natural persons—in particular, the right of free speech in the form of campaign contributions.

John Farmer Jr., dean of Rutgers Law School, whose Constitutional Litigation Clinic filed a brief in Kiobel, warned that if the court concludes that corporations “are not persons for purposes of the Alien Tort Claims act” but are persons for purposes of influencing elections, “the combined effect will be that corporations can advocate with impunity at home, and act with immunity abroad. The court should be careful that in defining a person, it does not create a monster.”

As the Supreme Court grapples with its decision, ExxonMobil is in the process of pulling out of Aceh, abandoning the dwindling reserves of the Arun gas facility. But losing or settling the case wouldn’t noticeably move ExxonMobil’s considerable bottom line. Of more concern might be the negative fallout that comes from being publicly associated with atrocities.

“You would think that ExxonMobil doesn’t care,” says Marco Simons, legal director for the advocacy group EarthRights International, who filed a brief for the plaintiffs in the ExxonMobil case. “But this matters to even big oil companies. They face a tremendous vulnerability to their reputation, not unjustifiably, but because the evidence shows complicity in series of abuses. Directors do not want to be associated at cocktail parties with mass graves in Indonesia.”

The report was produced in association with the media NGO Project Word (projectword.org), a project of the Tides Center, with reporting assistance from Hannah Rappleye and Lisa Riordan Seville. For more on this story, visit projectword.org/aceh. This reporting was made possible by grants from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Mailman Foundation.