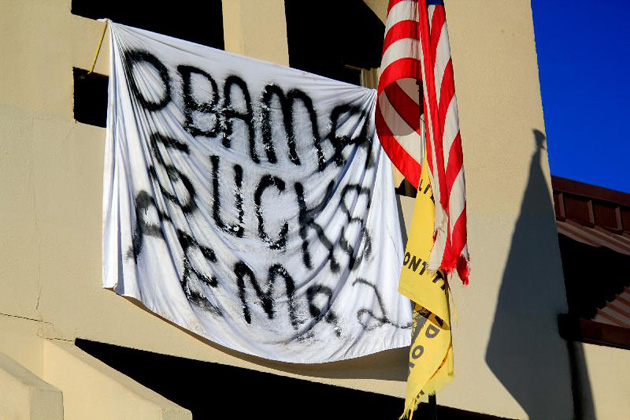

A sign in Oceanside Long Island.Photo: Climate Desk.

This story first appeared on the Wired website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

After two years as the new third rail of American politics, climate change is poised for a return to Capitol Hill.

In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy and this summer’s drought, the political atmosphere seems to have changed. Washington observers say the cost of extreme weather is too big and obvious to be ignored.

What form climate legislation could take remains undetermined, but the Democrats’ failed 2010 cap-and-trade bill won’t likely be reheated. There’s a demand for new ideas—and, at least for now, those ideas will be heard.

“Insurance companies are talking about this. Governors and mayors are. Communities all over the country are having serious conversations about resilience and extreme weather,” said Eric Pooley, senior vice president of the Environmental Defense Fund, a centrist advocacy group.

Continued Pooley, “It used to seem abstract, like something to protect our grandchildren from. Now it’s something we want to protect ourselves and our living children from. It doesn’t mean there won’t be battles over the specifics of the ideas, but it does mean we might be able to have a grown-up conversation.”

Pooley’s optimism may ring hollow to people who remember the 2010 climate change bill, a cap-and-trade plan for carbon pollution that imploded in a storm of partisan acrimony, or see in the post-election political landscape little reason to think Congress will achieve any more bipartisan agreement now than in the past several gridlocked years.

There are, however, some practical reasons that the new Congress will be less dysfunctional, and climate change, so notably absent from the presidential campaign, was thrust by Sandy into the national spotlight.

Climate change’s influence on Sandy is actually still uncertain—it’s safe to say that unnatural warming added an extra eight inches to eastern US sea levels, but harder to know if an abnormally off-kilter polar jet stream kept the storm from moving harmlessly out to sea—but more apparent in other calamities.

A recent report by German insurance giant Munich Re put the US weather disaster bill at $1 trillion since the early 1980s, with climate change as a main driver. While the economy is still the top priority among US voters, climate’s economic impacts are more evident than ever.

“We all need to come to terms with the cost of climate change,” wrote the editors of Bloomberg.com in a recent editorial. Michael Bloomberg, the mayor of New York City, endorsed President Obama precisely because he was more open than Mitt Romney to addressing climate issues*.

Of course, anything that emerges from Congress will need bipartisan support, but Democrats and Republicans have quietly started talking about climate, said Josh Freed, director of energy policy at centrist think tank Third Way. Ideas have been floated that both sides could agree on.

“If you break the challenges that climate change presents down into their parts, there are real opportunities over the next four years,” Freed said. “The bright side of Congress not having worked much over the last two years is that we have a surplus of ideas that could work.”

Andrew Moylan, a senior fellow at R Street, a free-market think tank, said that “we’re starting to hear more of these discussions happening in Washington.” A return to 2010’s cap-and-trade program would be doomed, he said, a sentiment echoed by Freed and Pooley, but conservatives might be open to other approaches.

An opening piece of bipartisan common ground could be mitigation and adaptation: infrastructure improvements that make municipalities less vulnerable to extreme weather. Mayor Bloomberg’s own PlaNYC project is a blueprint for some of these approaches.

Reforms that dovetail neatly with budget savings could also be popular, said Moylan. These could include cutting federal subsidies and insurance for development in sensitive areas, such as coastal wetlands and barrier islands.

Continued federal investment in clean energy and green technology is also up for debate. Many Republicans, especially in the House of Representatives, have resisted this spending, though it has been productive, especially in pushing electric and hybrid electric-gasoline cars to the verge of widespread consumer adoption, Freed said.

A less contentious option may be to encourage private investments. Legislation proposed by Sens. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.) and Chris Coons (D-Del.) would give financial incentives to green-tech investors that are currently restricted to investments in fossil fuel-based projects.

The energy industry itself will also come under scrutiny in the next several years, especially as the Environmental Protection Agency begins regulating greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, the largest US source of carbon pollution. That plan upheld in multiple court decisions but is opposed by many Republicans.

“I think we’re going to see a big fight as the administration moves forward on setting those standards,” said Alden Meyer, strategy director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a liberal advocacy group.

After-and-before Sandy photographs from coastal New Jersey. NASA Goddard Photo and Video/FlickrThat fight is probably unavoidable messy, but it may be easier to look at pollution from natural gas.

After-and-before Sandy photographs from coastal New Jersey. NASA Goddard Photo and Video/FlickrThat fight is probably unavoidable messy, but it may be easier to look at pollution from natural gas.

While natural gas is far cleaner burning than coal or oil, extracting it from the ground involves a certain amount of accidental leakage of methane and other extremely potent greenhouse gases.

“Stopping those leaks could give us the same benefits of shutting down one-third of all coal-fired power plants in the country,” said Pooley, whose Environmental Defense Fund is working with nine natural gas companies to reduce methane leaks. “There’s no law saying you need to reduce that leakage, and whether that happens at the state or federal level, that needs to happen.”

One idea that’s received widespread attention is a federal carbon tax, in which a per-ton tax is levied on carbon emissions by companies. While this might seem anathema to Republicans, and has indeed by opposed by some conservatives, including the Heritage Foundation, some are open to the idea.

“It has some pitfalls, but I think there’s potential for some sort of discussion around a revenue-neutral carbon tax,” said Moylan. Unlike a cap-and-trade approach, with its complicated markets in carbon credits, a carbon tax would be relatively straightforward, Moylan said. It could also be offset with cuts in other taxes, ultimately minimizing economic impacts.

“You can have a conversation around that,” Moylan said. “You can have a debate about what the contours might look like, and what might be necessary to get people not necessarily motivated by climate issues to buy in.”

Of course, if other countries, especially developing countries and fast-growing nations like China and Brazil, don’t also address climate change, action by the United States won’t be sufficient. But if the US doesn’t doesn’t lead, it can’t push other countries to do their share.

Freed said that climate and energy issues probably won’t take center stage for months yet, as the so-called fiscal cliff and tax policy reform are more pressing. After that, climate will be on the table.

“President Obama talked about climate change and innovation in virtually the same breath,” said Audubon Society president David Yarnold of the president’s victory speech. “I think that’s a really great reminder that there are solutions that are possible. It’s not going to be easy, but it can be done.”

Correction: Mayor Michael Bloomberg was originally identified as a Republican. He is a former Republican who switched to Independent in 2009. We apologize for the mistake.