<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&search_tracking_id=H-kN1hg0mFXm8OE_e8GU9A&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=coal+power+plant&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=132943211&src=LQGGrWIAoTk7IP0DWt20DQ-1-22">Claudia Otte</a>/Shutterstock

This story first appeared on the Atlantic website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

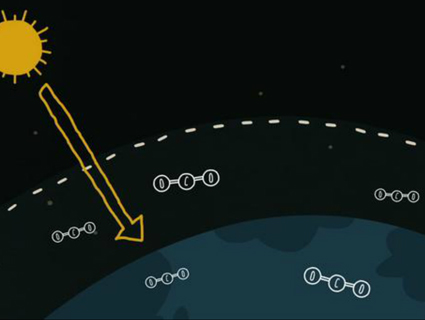

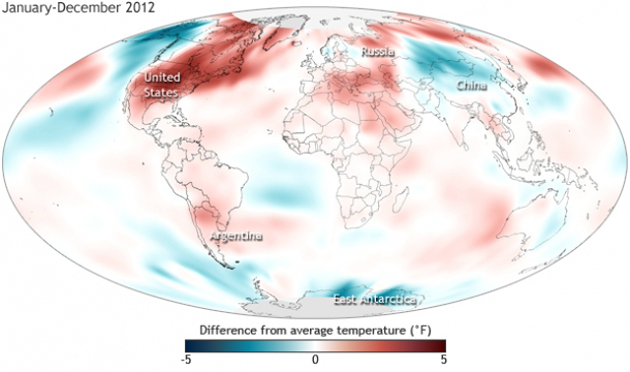

If we’re to avoid destructive climate fluctuations, scientists say we need to slow, and eventually halt, the emission of greenhouse gases that do and will continue to produce global warming.

A big chunk of our emissions come from the consumption of the fossil fuels — the coal, oil and gas that remain a crucial part of keeping the modern economy running. Not an easy task.

Let’s look at which fuels, and countries, produce the highest levels of carbon dioxide pollution, and how we can try to rein these emissions in.

In the United States green advocates are concerned about the climate impacts of all manner of new fossil fuel developments, but there is one culprit that stands above the rest. Potential emissions from increased oil production, more shale gas drilling, new pipelines, and exotic fuels pale in comparison to the possible carbon impact from coal reserves.

Coal is the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, and it’s cheap. China is consuming more coal every year, dwarfing the progress made in green energy elsewhere. And it will struggle to move away from this dependence, even as it pours money into renewables.

Finding a way to provide affordable renewable energy on a large-scale will be a necessary piece of making a major dent in carbon emissions.

American energy policy is supportive of investment in renewables, extending tax credits and seed funding to clean energy companies, from the successful Tesla Motors, to the not-so-successful flop of Solyndra.

This government finance for green start-ups has both detractors and supporters, but even without state support, the lower costs of renewable technologies are making the industry more and more attractive to private investment.

Renewables are an important piece of the puzzle, but come with their own obstacles. Solar and wind are intermittent energy sources around which wholly reliable systems have not been developed.

The conventional grid isn’t designed to deal with this. A possible solution is to build a nationally integrated, smarter grid to match energy supply across regions more exactly to demand. This would allow customers to see their energy consumption more clearly, and utilities to prevent blackouts more easily.

It has its own share of concerns, not least of which are how to protect an online grid against security threats. Consumers are also anxious about big data being used to infringe privacy and hike prices.

The shift to a smarter grid has already been made in some places like Florida, but is still in its early stages across the rest of the U.S. and the globe. It’s an area where China is forging ahead rapidly.

Climate change is global, in both the scope of its problems, and the sources of its solutions — it should be addressed globally.

In terms of the blame game, there are no easy targets. China is now the world’s biggest emitter, but U.S. emissions remain high, and historically America is by far the largest polluter. Few would disagree that America ought to bear a bigger burden of carbon-mitigation measures, but, to make an impact on climate change, the effort must be worldwide.

That’s why investment in renewable energy and smarter grids needs to be complemented by a globally binding emissions treaty.

The U.S. and China recently took baby-steps towards co-operation by agreeing to phase out harmful gases called hydroflourocarbons (HFCs), but many remain skeptical about the prospects for a treaty down the line.

If a treaty were enacted, countries would need to impose a carbon price — maybe through a tax or a cap-and trade system — to limit pollution. So far, Congress hasn’t passed any such legislation, despite considerable support at times. Obama is using executive authority to curb emissions.

For now, an IEA report sets its sights a little lower, but even the measures it recommends may be difficult to implement or less effective than hoped.

While the short-term politics look grim, taking a longer perspective, governments have helped push along the development of substantially cheaper solar and wind power, as well as supporting many other types of energy experiments. As the prices have come down, switching to cleaner power sources has become easier and the development of these industries has generated some interesting political constituencies like, say, wind farmers in Iowa, a key electoral state.

The point is: Energy transitions take a long time, and not just for technical reasons. But that doesn’t mean they don’t happen.