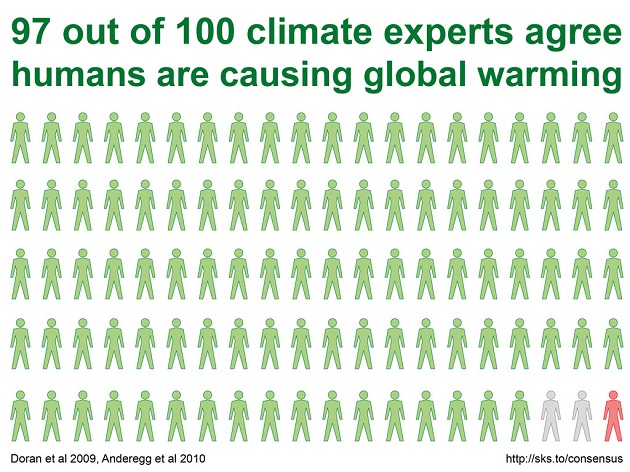

Scientists overwhelmingly agree that humans are causing global warming. But does telling conservatives this actually make a difference?<a href="http://www.skepticalscience.com/graphics.php?g=19">Skeptical Science</a>

As two top researchers studying the science of science communication—a hot new field that combines public opinion research with psychological studies—Dan Kahan and Stephan Lewandowsky tend to agree about most things.

There’s just one problem. The little thing that they disagree on—whether it actually works to tell people that there’s a “scientific consensus” on climate change—is a matter of huge practical significance. After all, many scientists, advocates, and bloggers are doing this all the time. Heck, Barack Obama and Al Gore are out there doing it. And the central message that the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sought to convey with its latest report, that scientists are now 95 percent certain that humans are driving global warming, is a message about scientific consensus.

In this episode of Inquiring Minds (click above to stream audio), Kahan and Lewandowsky debate this pressing issue. The discussion begins with a paper published in Nature Climate Change last year by Lewandowsky and two colleagues, providing experimental evidence suggesting a consensus message ought to work quite well.

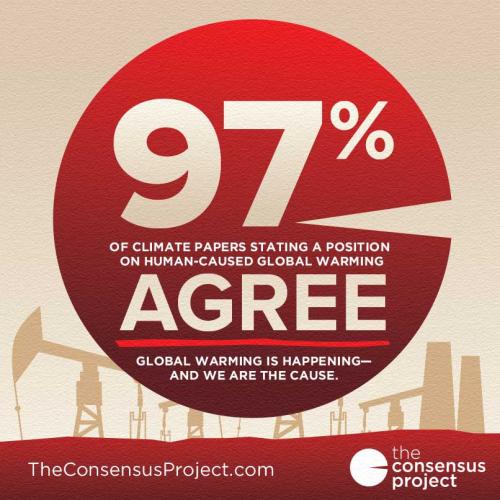

“We told people that 97 out of 100 climate scientists agree on the basic premise that the globe is warming due to greenhouse gas emissions,” explains Lewandowsky, who is based at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. “And what we found was that that boosted people’s acceptance of the scientific facts relating to climate change by a significant amount, and it did so in particular for people of a free-market worldview or ideology.” (The 97 percent figure comes from a recent study surveying the scientific literature on climate change.)

But Kahan, a Yale law professor who has extensively researched how our ideological predispositions skew our acceptance of facts, isn’t so sure. It’s not that he doubts Lewandowsky’s basic finding. But, he says, “when people get that kind of message in the world, there are all kinds of other influences that are filtering, essentially, the credibility of that message. If that would work, I would have expected it to work by now.”

The two researchers agree that political ideology—and in particular conservative fiscal or free market thinking—is an overwhelming factor preventing acceptance of climate science. “A position on climate change has become almost like a tribal totem,” says Lewandowsky. “I am conservative, therefore I cannot believe in climate change.” But the difference is that Lewandowsky thinks other factors can mitigate this reality—including a consensus message that works, in essence, through peer pressure. After all, who wants to fly in the face of what 97 percent of experts have to say?

“We know from my studies that if you can only tell people about the consensus, that it does make a huge difference to their belief,” Lewandowsky says.

At stake in this debate is much more than the practical question of how we get people to care about what’s happening to the planet. There’s a far deeper issue: Do facts actually work to change minds? Or should we simply resign ourselves to human irrationality, at least on issues where people have a deep emotional stake?

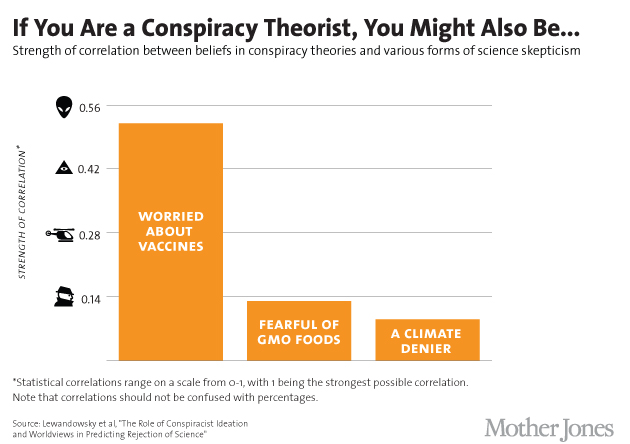

Kahan’s research provides an extensive documentation of how wildly biased we can be. After all, it’s not just that liberals and conservatives perceive completely different scientific realities on issues like climate change. It’s that as they grow more educated and scientifically literate, this problem becomes worse, rather than better, as the figure on the left demonstrates.

In response to such findings, many communications researchers have recommended framing strategies—in other words, placing potentially threatening information in a context that makes it more palatable to a particular person. Basically, it’s an acknowledgement of human irrationality and an attempted workaround. Thus, Kahan’s research suggests that you can make conservatives more accepting of climate science by framing it as supporting a free-market solution that they like for ideological reasons, such as nuclear power.

By contrast, what’s so striking about Lewandowsky’s “scientific consensus” message is that it isn’t really framed at all. There’s no sugar-coating present to make it go down easier on the political right. Rather, the message amounts to a blunt assertion of fact—in this case, the documented fact that climate scientists overwhelmingly agree. But in light of the research depicted above—as well as some research suggesting that political conservatives double down and become stronger in their beliefs when incorrect views are subject to a factual correction—there were plenty of reasons to fear this kind of approach would fail, at least in the face of strong ideology.

Still, Lewandowsky insists that it isn’t an all or nothing issue—in large part because there are so many different kinds of people out there to reach, not all of whom are dogged conservative ideologues. “I think underscoring the consensus is an arguably successful strategy for most people,” he says. “I also think reframing is a very important thing.”

The implications of this debate extend far beyond the climate issue. On evolution, for instance, the scientific consensus is even stronger than it is on climate change—a fact that evolution defenders have sought to cleverly emphasize by listing scientists named “Steve” who support evolution (so far, they’re at over 1,200 Steves). And again, Lewandowsky suspects that highlighting the overwhelming consensus on evolution is a winning message. “The consensus message is going to fail with some people, but that doesn’t mean that it wouldn’t also be effective overall,” he says.

So what’s the bottom line? Clearly, communications researchers have a lot of work to do to figure out how to reconcile the views of Lewandowsky and Kahan—both of whom, after all, are leading researchers in the field. So we can expect more studies aimed right at this central problem; in fact, they’re probably already in the works.

Meanwhile, both researchers agree that those going out and trying to communicate should test out different scientifically based approaches, trying to see which ones work in the real world. If anything, Kahan and Lewandowsky suggest that so far, those who actually practice communication aren’t relying on the latest science enough—or, in the case of many scientific institutions, aren’t investing enough in communications in the first place.

“It’s a mistake to assume that valid science will communicate itself,” says Kahan.

You can listen to the full interview with Kahan and Lewandowsky here:

This episode of Inquiring Minds, a podcast hosted by bestselling author Chris Mooney and neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas, also features a discussion of the strange and disturbing disappearance of moose across much of the United States, and of Oprah Winpfrey’s recent claim that self-described atheist swimmer Diana Nyad isn’t actually an atheist.

To catch future shows right when they release, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes. You can also follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook.