Illustration: Ross MacDonald

We stood in an airy San Francisco warehouse, staring at two plastic cups of gleaming mayonnaise. A golden retriever snored lightly in a patch of sunlight on the floor as Josh Tetrick, the 33-year-old founder of Hampton Creek Foods, waited for me to scoop up the fluffy, effulgent goop with a chunk of bread. Tetrick’s team of food scientists had tried making mayonnaise without eggs no less than 1,432 times. This formula was the 1,433rd.

“The egg is this unbelievable miracle of nature that has really been perverted by an unsustainable system,” Tetrick, a former West Virginia University linebacker and Fulbright Scholar, had explained to me earlier on our tour of the Hampton Creek Foods facility, a well-lit, cavernous space with rows of metal lab tables, bright red couches, and chalkboards.

Mod warehouse, hip startup, vegan eggs—it all struck me as a little too precious for the big time. But Tetrick is adamant that his product has a market beyond this rarefied universe. “We’re not just about selling and preaching to the converted,” he says. “This isn’t just going to happen in San Francisco, in a world of vegans. This is going to happen in Birmingham, Alabama. This is going to happen in Missouri, in Philadelphia.”

I let the eggless mayo dissolve in my mouth like a fine chocolate truffle. It tasted exactly like the real mayo that I’ve slathered on sandwiches countless times before. If I hadn’t known that it was fake, I never would have guessed.

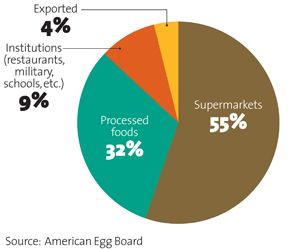

Over the next five years, Hampton Creek Foods, backed by $3 million from Sun Microsystems cofounder Vinod Khosla’s venture capital firm, will first hawk its product to manufacturers of prepared foods like pasta, cookies, and dressings—the processed products that use about a third of all the eggs in the United States. Then it will aim directly for your omelet with an Egg Beaters-like packaged product. The goal, Tetrick explains, is to replace all factory-farmed eggs in the US market—more than 80 billion eggs, valued at $213.7 billion.

Beyond Eggs isn’t the only fake-food startup in Silicon Valley. In the last couple of years, venture capitalists, including Bill Gates and the cofounders of Twitter, have been pouring serious cash into ersatz animal products. Their goal is to transform the food system the same way Apple changed how we use phones, or how Google changed the way we find information.

These new products are not the Boca Burgers of the ’90s, thinly concealed soy loaves designed to make vegetarians feel less ostracized at a barbecue. Rather, these entrepreneurs are determined to realign plant proteins into tasting and feeling exactly like meat. The goal is not a slightly improved Tofurky—it’s a product that could trick even the most discerning of steak eaters.

Sound a little grandiose? Well, yeah—but welcome to Silicon Valley, where you’d be laughed out of your pitch meeting if your startup didn’t promise to change the world. And food industry experts think that Tetrick and his ilk might actually have a shot. According to the market research firm Mintel, some 28 percent of Americans are trying to consume fewer meat products. Patty Johnson, a Mintel analyst, believes that this group, many of them following doctors’ orders to cut cholesterol, will be game to try meat substitutes that don’t require them to change their recipes. “Products that can mimic chicken the best will do well with that group—the reluctant vegetarians,” she says. “I think that they have a potential to carve out some share there in the mainstream consumer market.”

If there’s a ted Talk gene, Tetrick has it. A former sustainability associate for Citigroup, investment law adviser for Liberian president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and White House intern under President Clinton, he has bright eyes, tanned arms, and wiry hands that constantly pantomime his words. When Tetrick pitches Beyond Eggs, he begins with a story about how most of the United States’ eggs are produced by birds pumped full of corn, soy, and antibiotics in giant rows of cages. “Female birds are packed body to body in tiny cages so small they can’t flap their wings,” he says, enunciating every syllable in a slight twang that hints at his Alabama childhood. “They never see the sunlight. They never touch the soil.”

Tetrick is a vegan, but “as a company, we’re not about starting a conversation about whether you shouldn’t eat animals or you should eat animals,” he explains. Regular people should be able to eat what they want without guilt, he says: “Does my mom, when she eats a muffin, really have to subconsciously contribute to that type of unsustainable system? Can my little brother have a cookie? My God, can my dad have a Twinkie?”

To that end, Tetrick’s two engineers, six biochemists, and 11 food scientists are on a single-minded quest to hack the egg and its 22 functional properties—foaming, emulsifying, coagulating, and so on. Their workshop is more laboratory than kitchen; among its host of moisture and texture analyzers is a piston that measures the springiness of a muffin.

It all begins, says Megan Clements, Tetrick’s former director of “emulsion innovation,” with powdered protein isolate, also commonly used in veggie burgers and energy bars. “Our processing isn’t any more intensive than chickpea flour that you might buy from your local organic grocery store,” Tetrick says.

That’s not exactly true. Over the past two years, Tetrick estimates that his team has looked at the molecular weight of nearly a thousand plant proteins. His biochemists will buy pea protein isolate, for example, and run it through gel electrophoresis, a method also used in DNA analysis, to find out whether that protein can mimic the way an egg white foams up. The next step is processing—essentially putting the isolates through a mill with very particular specs for heat, speed, and pressure. He can’t tell me too much past that without getting into patented secrets, but he says that the more gentle the processing, the better. “It’s branched-chain amino acids, and if we mess with it too much, that protein will unfold,” he says. If that happens, the whole experiment collapses, and the scientists can no longer make the substance behave like an egg.

Tetrick’s product has already fooled some key testers. Eight months before my tour, at a high-profile Khosla Ventures investment conference, Beyond Eggs staged a blind tasting of its blueberry muffin and a real-egg version. Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair reported that he couldn’t tell the difference. Neither could Bill Gates—who was so impressed he became an investor in the company. This past March, Gates featured Beyond Eggs, along with a fake-meat company called Beyond Meat (no relation) and salt-substitute maker Nu-Tek Salt, in an online presentation called “The Future of Food.” In it, he enthused: “We’re just at the beginning of enormous innovation in this space. For a world full of people who would benefit from getting a nutritious, protein-rich diet, this makes me very optimistic.”

Like Beyond Eggs, Beyond Meat is trying to fully replicate the experience of eating animal products: It currently makes impostor chicken strips and soon plans to move on to artificial ground beef and pork. Backed by Obvious Corp., the investing team launched by Twitter’s cofounders, as well as Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (one of the first venture capital firms to invest in Amazon and Google), Beyond Meat sees itself as part of the transition to a future in which “meat” can mean hyper-realistic plant substitutes. Beyond Meat’s Chicken-Free Strips are sold at Whole Foods and are set to hit conventional supermarkets by early 2014.

“We call it ‘transformative agriculture,'” explains Amol Deshpande, a general partner at Kleiner Perkins. Beyond Meat is the first food company Kleiner Perkins has funded, but Deshpande says the firm is expanding: “There are going to be 9 billion people on the planet to feed. We have to think more broadly.” Indeed, Beyond Meat calculates that its process is 55 times more efficient than beef farming when it comes to land use, and 18 times more efficient than raising poultry.

If making impostor eggs for use in mayo and muffins is a challenge, creating fake meat that actually feels and tastes like muscle is a much harder one, as anyone who has eaten a seitan sandwich can attest. Herbert Stone, former president of the Institute of Food Technologists and a member of the first Apollo space mission’s food science team, remembers encountering this dilemma around 1963, when the price of beef was skyrocketing and he began helping companies develop soy-based extenders. Since then, Stone says that he has consulted for three or four fake-meat companies and has seen 15 or 20 (he won’t say which ones) whose products have failed over the years. Current clients looking to perfect fake meat include several Chinese manufacturers.

The biggest challenge in making meat alternatives, Stone says, is that it’s almost impossible to replicate the particular mix of protein and fat found in animal products. The fat in meat provides flavor, and heat from cooking changes the protein to create meat’s distinctive texture. Soy protein, on the other hand, is fat free. Simply mixing it with, say, coconut oil, doesn’t work—the bond between animal fats and proteins is notoriously difficult to replicate. “The problem always was that it didn’t taste like a burger,” Stone says. “When I would talk with companies about this, I’d ask: ‘Why do you want to create an imitation and call it that? Why not just create a product and call it something else?'” But food marketers didn’t want vegetable patties or soy croquettes—they wanted to sell burgers. “It was like banging your head against a concrete wall,” Stone says. A product that is genuinely indistinguishable from meat, though, might be a different story—and Stone believes that Beyond Meat just might be able to pull it off. “They’re smart people, I think; that’s an opportunity,” he says. “The big question is that they have to come up with a line of products that has appeal to the consumer. I think it’s just the beginning.”

After sampling Beyond Meat’s Southwest-style Chicken-Free Strips, I tended to agree with Stone’s cautious optimism. They really did taste startlingly similar to what I remember from my pre-vegetarian days. There was a tissuelike resistance—I could tear off strands that felt like muscle. Granted, without any sauce or fixings, the strips’ flavor resembled that of a grilled Chick-fil-A breast abandoned in a cup holder for a few days. But that didn’t stop me from finishing the whole 12-ounce package.

The lifelike texture is the result of nearly a decade of tinkering at the University of Missouri, where Beyond Meat’s lead researcher, Fu-hung Hsieh, found a way to put soy and pea proteins through an extruder to realign them into fleshlike strips. Like Beyond Eggs, the Beyond Meat team uses a combination of heating, cooling, and pressure to break the proteins’ molecular bonds and put them back together, but the complex sequencing of that process is what Beyond Meat claims separates its products from dull fake-meat patties already on shelves.

“If you’re comfortable with how bread is made, you’d be comfortable with how our product is made,” Ethan Brown, Beyond Meat’s founder and CEO, told me. But he wouldn’t go into specifics about his company’s energy balance sheet—this information, he said, is proprietary. That lack of transparency is part of why some foodies dismiss meat substitutes in favor of sustainably raised real meat. “I think it’s a big can of worms,” Will Turnage, a Brooklyn-based food app designer, told me. Turnage is the creator of Carv, an online platform that helps users figure out which farms, slaughterhouses, and packers their supermarket meat came from. The app took first prize last year at New York’s Hack//Meat, a periodic event where tech types compete to find solutions to food problems. “What I worry about is, okay, we’re going to create an egg substitute, and then 10 years down the road, we’re going to realize there’s some unknown effect,” Turnage says. “It’s an overly dramatic comparison, but—look at what happened with asbestos.”

Shell Game

Every year, US laying hens produce 80.5 billion eggs. Where do they all end up?

True, there’s a little more chemical complexity to the raw materials for fake eggs and meat than what goes into a loaf of bread. Commercial soy isolate, for example, is commonly produced by bathing soybeans in a chemical compound called hexane, whose emissions are a main component in smog. Soybean processing accounted for 42 percent of hexane emissions cataloged by the Environmental Protection Agency in 2011. Small amounts of hexane have also turned up on some soy products—a troubling finding, since it’s a known carcinogen and neurotoxin. The Food and Drug Administration doesn’t regulate hexane, and it’s unclear how any residue might affect consumers, but there are other risks too: In 2003, for example, hexane was released during routine maintenance at an Iowa soybean plant. The resulting explosion killed two workers.

Tetrick’s Hampton Creek Foods doesn’t use soy in its egg products, but Beyond Meat lists it as a primary ingredient in its Chicken-Free Strips. “Hexane is not part of Beyond Meat’s recipe or production process,” Hilary Martin, a Beyond Meat spokeswoman, told me in an email. But Martin confirmed that Beyond Meat buys soy protein isolate from DuPont-owned Solae, whose Illinois plant released 281,000 pounds of airborne hexane in 2011, according to the EPA. Martin said that Solae provides Beyond Meat with data that shows no traces of hexane on the protein isolate. When I asked Brown whether he was concerned about hexane, he called the residue complaint “a red herring.” He said he had never heard that it was an air pollutant but promised he’d look into it.

How much will consumers really want to know about how the fake sausage is made? We may soon find out. Last spring, the Founders Fund, one of the first venture capital firms to invest in Facebook, Napster, and Palantir, invested $1 million in Beyond Eggs—and in September, Whole Foods stores in Northern California began selling the fake mayo I tried. In early 2014, Beyond Meat’s plant-based beef crumbles will make their supermarket debut. Though it won’t divulge any details, Hampton Creek Foods says it is also working with Heinz (which wouldn’t comment) and other Fortune 500 companies to roll out more products.

Of course, some food technologists are already thinking beyond Beyond Meat. NASA began investigating in vitro meat grown from turkey cells as early as 2001, and by 2008, PETA offered a $1 million reward to anyone who could produce chicken from a petri dish. Four years later, some 30 companies had entered the in vitro game. In August, using blood from fetal calves to nourish cow cells, a Dutch team finally succeeded in making the world’s first lab burger—a two-year, $332,000 project funded by Google cofounder Sergey Brin. The live-streamed taste test aired on more than a thousand TV channels around the world. According to Chicago food critic Josh Schonwald, one of the three testers who sampled the burger, the texture was good but the taste was too lean. “I miss the fat,” he said. Still, “the aim is to, of course, make a consumer product out of it,” lead scientist Mark Post said in a promotional video. “It may take 10 years, maybe even earlier.”

How big is the factory farm economy?

US livestock requires vast amounts of water and grain—and takes a major toll on the planet. —Maggie Caldwell

Brown isn’t worried about competition from lab-grown meat—not yet, at least. For now, he’s focused on brainstorming new plant-based products. One idea: a protein slab that tastes like fish and contains all its nutritional properties, but doesn’t actually look like a fillet. “Would that be interesting?” he asked me, seeming genuinely curious. “Or do you think we would perfectly have to mimic fish? Because we could do that.”

Pure hubris? Maybe. But braggadocio is a job requirement for guys like Brown and Tetrick—even if their products aren’t perfect yet, their pitches are. In his most impassioned speeches on fake meat, Brown often refers to the advent of the automobile: Cars were not another kind of horse-drawn carriage. “We’re not trying to be an alternate to chicken,” he says. “We’re trying to be a new chicken.”